Oregon Trail facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Oregon Trail |

|

|---|---|

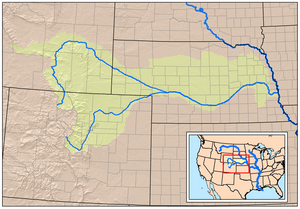

The route of the Oregon Trail shown on a map of the western United States from Independence, Missouri (on the eastern end) to Oregon City, Oregon (on the western end)

|

|

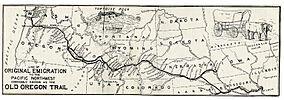

Map from The Ox Team, or the Old Oregon Trail 1852–1906, by Ezra Meeker

|

|

| Location | Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, Washington, Oregon |

| Established | 1830s by mountain men of fur trade, widely publicized by 1843 |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Oregon National Historic Trail |

The Oregon Trail was a very long wagon route in North America. It stretched about 2,170 miles (3,490 km) from the Missouri River to valleys in the Oregon Territory. This trail helped many people move west across the United States.

The eastern part of the trail went through what are now the states of Kansas, Nebraska, and Wyoming. The western part crossed Idaho and Oregon. Fur traders and trappers first explored this route between 1811 and 1840. At first, you could only travel it on foot or horseback.

By 1836, the first group of people with wagons left Independence, Missouri. A wagon trail was ready up to Fort Hall, Idaho. Over time, the trail was cleared all the way to the Willamette Valley in Oregon. This completed what we now call the Oregon Trail. Bridges, shortcuts, and ferries later made the trip faster and safer.

Many different routes started in Iowa, Missouri, or Nebraska Territory. They all met near Fort Kearny, Nebraska. From there, the trail led to rich farmlands west of the Rocky Mountains. About 400,000 settlers, farmers, miners, and families used the Oregon Trail. The busiest years were from 1846 to 1869. Other trails like the California Trail and Mormon Trail also used parts of the Oregon Trail.

The trail became less used after the first transcontinental railroad was finished in 1869. The train made the trip west much faster, cheaper, and safer. Today, modern highways like Interstate 80 and Interstate 84 follow parts of the old trail. They pass through towns that first grew to serve the Oregon Trail travelers.

Contents

- History of the Oregon Trail

- Early Explorers: Lewis and Clark

- Pacific Fur Company and New Discoveries

- British Control: Hudson's Bay Company

- The "Great American Desert"

- Fur Traders and Explorers

- Missionaries and Early Settlers

- The Great Migration of 1843

- Oregon Country and Land Claims

- Women on the Trail

- Mormon Emigration

- California Gold Rush

- Later Trail Use and Decline

- Routes of the Oregon Trail

- Travel Equipment

- Trail Statistics

- Other Ways to Go West

- Legacy of the Trail

- Images for kids

- See also

History of the Oregon Trail

Early Explorers: Lewis and Clark

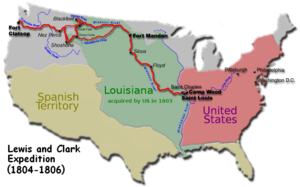

The first land route across the United States was mapped by the Lewis and Clark Expedition. This happened between 1804 and 1806. President Thomas Jefferson asked them to find a way to the Pacific Ocean. He hoped for a direct water path for trade.

Lewis and William Clark did find a way to the Pacific. But it was not easy for wagons to use. The mountain passes they found were too difficult. On their way back in 1806, they found a shorter route. However, it was still too rough for wagons. Also, Blackfoot tribes controlled that area.

The expedition showed that there was no "easy" way through the northern Rocky Mountains. But they did map the river valleys that would later be part of the Oregon Trail. They showed the way for brave mountain men who would soon find a better path.

Pacific Fur Company and New Discoveries

John Jacob Astor started the Pacific Fur Company (PFC) in 1810. It was part of his American Fur Company. The PFC worked in the Pacific Northwest fur trade. One group of PFC workers traveled by ship. Another group went overland, led by Wilson Price Hunt. Hunt's group was looking for new supply routes.

Hunt's overland group avoided the Niitsitapi by going south into Wyoming. They crossed the Teton Range and reached the Snake River in Idaho. They tried to use the river for travel. But they found it had steep canyons and dangerous rapids. They had to walk the rest of the way to Fort Astoria. This trip showed that parts of the Snake River plain were passable for pack animals. This knowledge helped shape the early Oregon Trail.

A PFC partner named Robert Stuart led a small group back east. They planned to follow Hunt's path. But fear of Native American attacks made them go further south. There, they found South Pass. This was a wide and easy way over the Continental Divide.

Stuart's group continued east along the Sweetwater River and North Platte River. They reached the Missouri River in 1813. This route seemed good for wagons. Stuart's detailed notes described most of the path. But because of the War of 1812, this route was not used much for over 10 years.

British Control: Hudson's Bay Company

In 1811, David Thompson of the North West Company reached Fort Astoria. He had mapped much of western Canada. He claimed the land for Britain. When the War of 1812 started, Fort Astoria was sold to the North West Company.

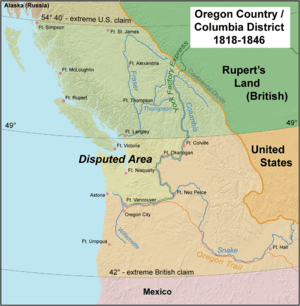

By 1821, the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) and the North West Company merged. The new HBC had control over the Columbia District, also called Oregon Country. They tried to stop American trappers and settlers from coming to the Pacific Northwest.

American missionaries and settlers began arriving in the late 1820s. The HBC manager at Fort Vancouver, John McLoughlin, helped them. He gave them loans, medical care, and supplies. McLoughlin was later called the Father of Oregon. By the early 1840s, thousands of Americans arrived. They soon outnumbered the British settlers.

The HBC built a larger Fort Vancouver in 1825. It became the main center in the Pacific Northwest. Ships from London brought supplies and traded for furs. When American settlers started coming in the 1840s, Fort Vancouver was their last stop. They could get supplies and help before starting their new homes.

By 1840, the HBC had forts like Fort Hall, Fort Boise, and Fort Nez Perce on the western Oregon Trail. These forts often gave much-needed help to early pioneers.

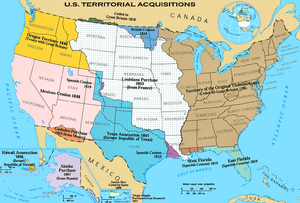

The fur trade slowed down in the 1840s. This made the Pacific Northwest less valuable to the British. In 1846, the Oregon Treaty was signed with Britain. This treaty set the Canada–United States border at the 49th parallel. The United States gained most of what it wanted. It had a good border and access to Puget Sound.

The "Great American Desert"

Early explorers like Zebulon Pike (1806) and Stephen Long (1819) called the Great Plains "unfit for human habitation." They saw a lack of trees and water. But many reports also talked about huge herds of Plains Bison living there.

In the 1840s, the Great Plains did not seem good for settlement. The U.S. government had set it aside for Native American settlements. Oregon, however, seemed free for the taking. It had fertile land, a healthy climate, forests, big rivers, and potential seaports. It also had only a few British settlers.

Fur Traders and Explorers

Fur trappers worked for fur trading companies from 1812 to 1840. They explored almost every stream looking for beaver. Famous fur traders included Jedediah Smith, William Sublette, and Jim Bridger. They mapped rivers and mountains. They also kept diaries of their travels. Many became guides when the trail opened for general travel.

In 1823, Jedediah Smith and Thomas Fitzpatrick found the Sweetwater River. They tried to float their furs down it but found the river too rough. On July 4, 1824, they hid their furs under a rock they named Independence Rock. They then walked to the Missouri River. They had found the same route Robert Stuart took in 1813.

Up to 3,000 mountain men explored the Rocky Mountains. They usually traveled in small groups for safety. They trapped beaver and sold the skins. In 1825, the first American Rendezvous took place. This was an annual event where traders met trappers to buy furs.

In 1830, William Sublette brought the first wagons up the Platte, North Platte, and Sweetwater rivers. He crossed South Pass to a fur trade meeting. His crew cleared the way. This showed that the eastern part of the Oregon Trail could be used by wagons. By 1840, the demand for beaver hats dropped. Fur prices fell, and trapping almost stopped.

The Platte River was too shallow and muddy for boats. But its valley became an easy road for wagons. It was nearly flat and went almost due west.

U.S. government explorers also mapped parts of the Oregon Trail. Captain Benjamin Bonneville explored from 1832 to 1834. He brought wagons across South Pass to the Green River. His travels were written about by Washington Irving in 1838. John C. Frémont and his guide Kit Carson led expeditions from 1842 to 1846. Their detailed maps of California and Oregon were published around 1848.

Missionaries and Early Settlers

In 1834, the Dalles Methodist Mission was founded by Reverend Jason Lee. In 1836, Henry H. Spalding and Marcus Whitman traveled west. They started the Whitman Mission in Washington. Their wives, Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Hart Spalding, were the first European-American women to cross the Rocky Mountains.

They traveled with fur traders to Fort Hall. There, they left their wagons and used pack animals. They reached Fort Walla Walla and then Fort Vancouver for supplies. Other missionaries also set up missions in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.

On May 1, 1839, the Peoria Party set out from Illinois. They wanted to settle Oregon for the United States. They were among the first to travel most of the Oregon Trail. They carried a flag saying "Oregon Or The Grave." Nine of them eventually reached Oregon.

In September 1840, Robert Newell and Joseph L. Meek reached Fort Walla Walla with three wagons. They had driven them from Fort Hall. Their wagons were the first to reach the Columbia River by land. They opened the last part of the Oregon Trail to wagon traffic.

In 1841, the Bartleson-Bidwell Party was the first group to use the Oregon Trail to move west. Half of them went to Oregon. They left their wagons at Fort Hall. In 1842, the second organized wagon train left Missouri with over 100 pioneers.

The Great Migration of 1843

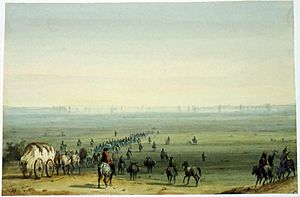

In 1843, about 700 to 1,000 people left for Oregon. This was called "The Great Migration." Marcus Whitman joined the wagon train. At Fort Hall, Hudson's Bay Company agents told pioneers to leave their wagons. Whitman disagreed. He believed the group was large enough to build any needed road improvements.

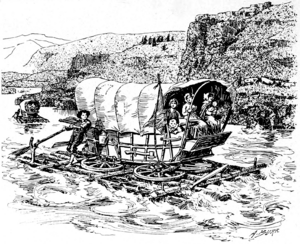

The biggest challenge was in the Blue Mountains of Oregon. They had to cut a trail through thick trees. Wagons stopped at The Dalles because there was no road around Mount Hood. Wagons had to be taken apart and floated down the dangerous Columbia River. Animals were herded over the rough Lolo trail. Most settlers arrived in the Willamette Valley by early October. A wagon trail now existed from the Missouri River to The Dalles.

In 1846, the Barlow Road was finished around Mount Hood. This made a rough but complete wagon trail from the Missouri River to the Willamette Valley. It was about 2,000 miles (3,200 km) long.

Oregon Country and Land Claims

In 1843, settlers in the Willamette Valley created the Organic Laws of Oregon. This organized land claims. Married couples could get up to 640 acres (2.6 km²). Single settlers could claim 320 acres (1.3 km²). These claims were not official at first. But the U.S. government later honored them in the Donation Land Act of 1850. After 1854, land was no longer free. It cost $1.25 per acre.

Women on the Trail

Women on the Oregon Trail faced very hard work. They had to collect "buffalo chips" for fires. They also loaded and unloaded wagons. Sometimes, they even drove oxen teams. They helped keep their families peaceful and healthy. Women were the backbone of life on the wagon trail. They took on their regular duties and many tasks usually done by men.

Historians say that women experienced the West differently from men. Men might accept dangers for money. But women saw dangers as threats to their family's safety. Once they arrived, women played a bigger role in building communities. This gave them more power than they had back East.

Women's diaries show their feelings. They wrote about the many deaths on the trail. Anna Maria King wrote in 1845 about losing eight family members. Martha Gay Masterson, who was 13, wrote about finding graves and skulls.

Women also gave advice to family back home. They told them how to prepare for the trip. They also wrote about the Western landscape. Betsey Bayley described mountains that looked like volcanoes. She also mentioned valleys covered in a white crust that tasted like baking soda.

The trail allowed women to take on new roles. They became "reporters, guides, poets, and historians" in their journals. They wrote about plants and animals to help feed their families. Women showed great resourcefulness and creativity on the trail.

Mormon Emigration

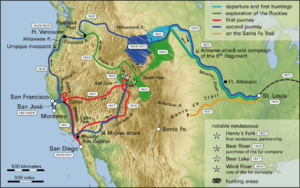

After facing hardship, Mormon leader Brigham Young led his followers west. They went to the Salt Lake Valley in Utah. In 1847, Young led a fast-moving group from Winter Quarters, Nebraska. They were to set up farms and settlements for others coming later.

The Mormons followed the northern bank of the Platte River. They went to Fort Laramie in Wyoming. After 1848, thousands of Mormons traveled each year. Their wagon trains moved slower than others because they had more women and children. They took about 100 days to travel 1,000 miles (1,600 km) to Salt Lake City.

At Fort Bridger, the Mormon Trail left the main path. They followed the Hastings Cutoff through the Wasatch Mountains. Between 1847 and 1860, over 43,000 Mormon settlers went to Utah. Many thousands more on the California and Oregon Trails also passed through Utah. After 1848, travelers could resupply in Salt Lake Valley. Then they rejoined the main trail near the City of Rocks in Idaho.

The Mormons set up ferries and improved the trail. These helped later travelers and earned money. Ferries across the North Platte and Green River charged tolls for non-Mormons.

California Gold Rush

In January 1848, gold was found in California. This started the California gold rush. Many men from Oregon went to California to find gold. They helped build new wagon roads. Many returned with gold, which helped Oregon's economy. Over the next 10 years, gold seekers greatly increased traffic on the Oregon and California Trails.

The "forty-niners" often chose speed over safety. They used shortcuts like the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff in Wyoming. This saved seven days but crossed 45 miles (72 km) of desert without water. 1849 was also the first year of large cholera outbreaks. Thousands are thought to have died along the trail. Most were buried in unmarked graves.

The gold rush brought mostly men to California. Women were very few. This gave women chances to do jobs not usually open to them. The gold rush continued for several years. Many thousands more moved to California for new opportunities.

Later Trail Use and Decline

The trail was still used during the American Civil War. But traffic dropped after 1855. This was when the Panama Railroad was finished. Ships and steamships offered faster and cheaper travel to the West Coast.

Many ferries and toll bridges were built over the years. This made river crossings safer and faster. The cost of travel increased by about $30 per wagon. But the trip time dropped from 160-170 days in 1843 to 120-140 days in 1860.

In 1859, Captain James H. Simpson found a shorter route across Nevada. The Army improved this trail for wagons and stagecoaches. In 1860, the Pony Express started. Riders delivered mail day and night. They used relay stations every 10 miles (16 km) for fresh horses. The Pony Express used many stations along the Oregon Trail.

In 1861, the first transcontinental telegraph line was built. It followed much of the same route. Stage lines also carried mail and passengers. They could get people from the Midwest to California in 25-28 days. The Pony Express stopped in 1861 because the telegraph took over. This combined route is now called the Pony Express National Historic Trail.

After the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, the Oregon Trail was used less. The train trip took only seven days and cost as little as $65. Some people still used the trail into the 1890s. Today, modern highways and railroads follow parts of the trail. States and the federal government work to preserve trail landmarks. These include wagon ruts, old buildings, and "registers" where pioneers carved their names.

The Oregon Trail became a busy path from the Missouri River to the Columbia River. Many side trails grew as people found gold, silver, and farming chances. Traffic became two-directional. Towns grew along the trail. By 1870, the population in these Western states grew by about 350,000 people. Most of these new residents traveled parts of the Oregon Trail.

The trail was also used to drive herds of cattle, horses, sheep, and goats. Livestock was much cheaper in the Midwest than in California or Oregon. Even with losses, drovers made good profits. In 1852, there was even a drive of 1,500 turkeys from Illinois to California.

Routes of the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail had many shortcuts and variations. The main route followed river valleys. This was important for grass and water.

The main starting points were Independence, Missouri, or Westport (now part of Kansas City). Later, other towns like St. Joseph became popular starting points.

The trail usually ended at Oregon City. This was the proposed capital of the Oregon Territory. But many settlers stopped earlier. They settled in good spots along the way. Trade with other pioneers helped these early settlements grow.

Over time, the trail became easier. Ferries and toll bridges were built at river crossings. Bad parts of the trail were fixed or bypassed. The average trip time dropped from about 160 days in 1849 to 140 days 10 years later.

Many other trails shared parts of the Oregon Trail. These included the Mormon Trail to Utah, the California Trail to California, and the Bozeman Trail to Montana. The Oregon Trail was more like a network of paths. Travelers spread out to find water, wood, and grass. Dust was a big problem. In some areas, 20 to 50 wagons traveled side-by-side.

Parts of the trail in Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon are now on the National Register of Historic Places. The whole trail is a National Historic Trail.

Missouri and Iowa

The main starting point was Independence, Missouri. Travelers had to cross the Missouri River by ferry. They followed the Santa Fe Trail into Kansas. Another busy starting point was St. Joseph, Missouri. It was a bustling frontier town. St. Joseph had good steamboat connections to other cities. It was the westernmost point reachable by rail before 1865.

In 1846, the Mormons settled temporarily in Iowa and Nebraska. They set up towns like Kanesville, Iowa (now Council Bluffs). This became a major starting point for many travelers. Mormons also set up ferries across the Missouri River.

Kansas and Nebraska

From Missouri, the trail went into Kansas. It crossed the Kansas River near Topeka. West of Topeka, it angled northwest into Nebraska. It followed the Little Blue River.

In Nebraska, travelers crossed into towns like Omaha. Fort Kearny was about 200 miles (320 km) from the Missouri River. Most trails met near Fort Kearny. It was the first chance to get emergency supplies, repairs, or medical help.

The Platte River in Nebraska and Wyoming was too shallow for boats. But its valley was an easy wagon path. It had water, grass, and buffalo chips for fuel. The water was silty but could be used.

Travelers often saw hundreds of thousands of bison. They hunted bison for fresh meat and jerky. In many places, Native Americans burned the dry grass each fall. So, travelers used dried buffalo dung for cooking fires. It burned fast but hot. Collecting buffalo chips was a common chore for children.

Travelers on the south side of the Platte crossed the South Platte River. Then they continued up the North Platte River Valley into Wyoming. Before 1852, those on the north side crossed the North Platte at Fort Laramie. After 1852, they used Child's Cutoff to stay on the north side.

Famous landmarks in Nebraska include Courthouse and Jail Rocks, Chimney Rock, and Scotts Bluff. Today, Interstate 80 and U.S. Highway 30 follow much of the old trail.

Cholera on the Platte River

Preferred camping spots were along freshwater streams. But these spots became sources of cholera during outbreaks (1849–1855). Thousands of people used the same spots with poor sanitation. Cholera caused severe diarrhea. This spread the disease even more. People did not know what caused cholera or how to treat it. Thousands died and were buried in unmarked graves.

Most cholera outbreaks did not go further west than Fort Laramie. The faster-flowing rivers in Wyoming may have helped stop the spread of germs.

Wyoming

After crossing the South Platte River, the Oregon Trail followed the North Platte River into Wyoming. Fort Laramie was a major stop. It was a former fur trading post. The U.S. Army bought it in 1848 to protect travelers. It was the last army outpost until the coast.

The trail continued up the North Platte River. Then it crossed to the Sweetwater River Valley. Independence Rock is on the Sweetwater River. The Sweetwater had to be crossed many times. Then the trail went over the Continental Divide at South Pass.

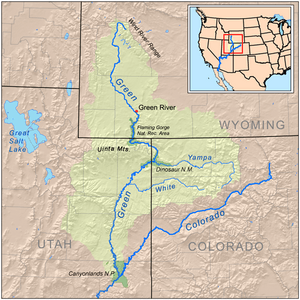

From South Pass, the trail went southwest. It crossed Big Sandy Creek before reaching the Green River. The Green River was deep, wide, and dangerous. Three to five ferries were used during busy times. After crossing the Green, the main trail went to Fort Bridger. From there, the Mormon Trail split off. The main trail continued northwest to the Bear River Valley.

Two major shortcuts were used in Wyoming. The Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff (1844) saved about 70 miles (110 km). It left the main trail west of South Pass. It crossed 45 miles (72 km) of waterless desert. Then it reached the Green River.

The Lander Road (1858–59) was about 80 miles (130 km) shorter than the main trail. It had good grass and water. But it was steeper and rougher. In 1859, 13,000 emigrants used the Lander Road.

Many landmarks are along the trail in Wyoming. These include Independence Rock, Ayres Natural Bridge, and Register Cliff.

Idaho

The main Oregon and California Trail went north from Fort Bridger. It followed the Bear River Valley into Idaho. In the Thomas Fork Valley, travelers faced Big Hill. This was a tough climb and descent. In 1852, Eliza Ann McAuley found a shortcut around Big Hill.

About 5 miles (8 km) further, they passed Montpelier. The trail followed the Bear River to Soda Springs. Pioneers liked the hot carbonated water there. West of Soda Springs, the main trail turned northwest. It followed the Portneuf River valley to Fort Hall, Idaho. Fort Hall was a fur trading post on the Snake River. Travelers could get aid and supplies there. Mosquitoes were a constant problem.

At Soda Springs, a branch of the Lander Road rejoined the main trail. Another shortcut, Hudspeth's Cutoff (1849), went west from Soda Springs. It bypassed Fort Hall. It saved time but crossed five mountain ranges. Its main benefit was spreading out traffic.

West of Fort Hall, the trail followed the south side of the Snake River. It passed Massacre Rocks and Register Rock. Near the Raft River, the California Trail split from the Oregon Trail. California-bound travelers followed the Raft River southwest.

The Snake River was deep and fast. There were few safe places to cross. Two fords were near Fort Hall. Travelers on the Oregon Trail North Side Alternate (1852) and Goodale's Cutoff (1862) crossed to the north side. Some lost wagons over Salmon Falls.

Goodale's Cutoff (1862) was a spur on the north side of the Snake River. It was 230 miles (370 km) long. It went north from Fort Hall, past Arco, Idaho, and through Craters of the Moon National Monument. It ended at Old Fort Boise on the Boise River. This route was rough and dry. Wagon wheels often broke.

From Pocatello, the trail went west on the south side of the Snake River. It passed Shoshone Falls and other rapids. At Salmon Falls, Native Americans traded salmon.

The trail continued to Three Island Crossing (near Glenns Ferry). Here, most emigrants used ferries to cross the Snake River. The north side of the Snake had better water and grass. The last crossing of the Snake River was near Old Fort Boise. Travelers used bullboats or chained wagons together. Native American boys were often hired to swim the animals across.

The South Alternate of the Oregon Trail (1848) bypassed Three Island Crossing. It stayed on the south side of the Snake River. This route was rougher but avoided two dangerous river crossings. Today, Interstate 84 follows much of the Oregon Trail in Idaho. U.S. Route 30 follows it from Pocatello to Montpelier.

Boise, Idaho, has 21 monuments shaped like obelisks along its part of the Oregon Trail.

Oregon

After crossing the Snake River near Old Fort Boise, travelers entered Oregon. The trail went to the Malheur River, then up the Burnt River canyon. It continued northwest to the Grande Ronde Valley near La Grande. Then it reached the Blue Mountains. In 1843, settlers cut a wagon road through these mountains.

The trail went to the Whitman Mission until 1847. After the Whitmans were killed, the trail bypassed the mission. It went west to Pendleton, crossing the Umatilla River, John Day River, and Deschutes River. It ended at The Dalles. Interstate 84 in Oregon roughly follows the original trail to The Dalles.

At The Dalles, travelers were stopped by the Cascade Mountains and Mount Hood. Some took their wagons apart and floated them down the Columbia River. This was dangerous due to rapids. Their livestock were herded over the rough Lolo trail around Mount Hood.

The most popular route around Mount Hood was the Barlow Road. It was built in 1846 as a toll road. It cost $5 per wagon. It was rough but safer and cheaper than floating down the Columbia River.

Other routes included the Santiam Wagon Road (1861) and the Applegate Trail (1846). The Applegate Trail cut north from the California Trail to the south end of the Willamette Valley. U.S. Route 99 and Interstate 5 in Oregon roughly follow the Applegate Trail.

Travel Equipment

Wagons and Animals

Pioneers used three types of animals to pull wagons: oxen, mules, and horses. By 1842, many preferred oxen. Oxen were calm and healthy. They could keep moving in mud and snow. They could also eat prairie grasses, unlike horses. Oxen were cheaper to buy and care for. They traveled at a steady pace of about two miles an hour.

Shoeing oxen was hard because their hooves are split. Several men had to hold an ox while it was shod. Mules were also used. Some thought mules were more durable. Mules could also eat prairie grasses. But mules were expensive and often ill-tempered.

Three types of wagons were used:

- Conestoga wagons: heavy covered wagons.

- Covered wagons: lighter, often just covered farm wagons.

- Studebaker wagons.

Food and Water

Food and water were very important. Wagons usually carried a large water keg. Guidebooks told migrants what food to bring. T. H. Jefferson suggested 200 pounds (91 kg) of flour per adult. He said, "Take plenty of breadstuffs; this is the staff of life."

Common foods included crackers or hardtack. Southerners sometimes used cornmeal. Pioneers usually ate rice and beans only at forts. Boiling water was hard to do on the trail. Lansford Hastings recommended 200 pounds (91 kg) of flour, 150 pounds (68 kg) of bacon, 20 pounds (9.1 kg) of sugar, and 10 pounds (4.5 kg) of salt per person. Other items included tea, dried fruit, and vinegar.

Randolph B. Marcy, an army officer, wrote a guide in 1859. He suggested bringing less bacon. He advised driving cattle for fresh beef. He also said to store bacon in canvas bags to protect it from heat. Marcy recommended pemmican and storing sugar in rubber bags.

Canning technology was new. Canned goods like cheese, fruit, and meat were used by wealthier migrants. Canned foods were expensive and added weight. Marcy suggested dried vegetables instead.

Some pioneers brought eggs and butter. Some even brought dairy cows. Hunting provided fresh meat like American bison and deer. Pioneers also fished for catfish and trout. In desperate times, they would eat their animals or less common foods like jackrabbits or rattlesnakes.

Scurvy was a known disease. But pioneers rarely got it. They ate wild berries and onions along the trail. Marcy's guide said eating wild grapes and greens could prevent scurvy.

Middle-class families liked to prepare good meals. They often baked bread and pies using Dutch ovens. For cooking fuel, travelers used wood when available. More often, they used "buffalo chips"—dried bison dung. Buffalo chips burned hot and clean. Children often collected them.

Clothing and Supplies

Tobacco was popular for personal use and trading. Each person brought at least two changes of clothes and several pairs of boots. About 25 pounds (11 kg) of soap was recommended for a group of four. Wash days happened once or twice a month.

Most wagons carried tents for sleeping. But in good weather, people slept outside. They used thin mattresses, blankets, and ground covers. Wagons had no springs, so the ride was very rough. Few people rode in the wagons. It was too dusty and hard on the animals.

Travelers brought books, Bibles, and trail guides. They also brought writing supplies for letters and journals. Many men and boys carried a belt and folding knives. Sewing supplies like needles and thread were needed for repairs. Extra leather was used for shoes and harnesses.

Extra harnesses and wagon parts were often carried. Most had steel shoes for their animals. Tar helped repair injured ox hooves.

Travelers often shared goods and supplies. They could buy forgotten items from others or at forts. Blacksmiths at forts and ferries made repairs. Emergency supplies were often provided by people in California, Oregon, and Utah.

Non-essential items were often left behind to lighten the load. Other travelers would pick up discarded items. Some people made money by collecting abandoned goods and reselling them. In 1849, Fort Laramie was called "Camp Sacrifice." This was because so many items were left there before the hard mountain crossing.

Pioneers carried tools like axes, hammers, and shovels. These were used to clear roads, cut down banks for stream crossings, or repair wagons. They tried to do as little road work as possible. They often traveled on ridges to avoid brush.

Trail Statistics

About 268,000 pioneers used the Oregon Trail and its main branches (Bozeman, California, and Mormon Trails) from 1840 to 1860. Another 48,000 went to Utah. We don't know how many returned East.

Emigrants by Year

| Year | Oregon | California | Utah | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1834–39 | 20 | − | − | 20 |

| 1840 | 13 | − | − | 13 |

| 1841 | 24 | 34 | − | 58 |

| 1842 | 125 | − | − | 125 |

| 1843 | 875 | 38 | − | 913 |

| 1844 | 1,475 | 53 | − | 1,528 |

| 1845 | 2,500 | 260 | − | 2,760 |

| 1846 | 1,200 | 1,500 | − | 2,700 |

| 1847 | 4,000 | 450 | 2,200 | 6,650 |

| 1848 | 1,300 | 400 | 2,400 | 4,100 |

| Total | 11,512 | 2,735 | 4,600 | 18,847 |

| 1849 | 450 | 25,000 | 1,500 | 26,950 |

| 1850 | 6,000 | 44,000 | 2,500 | 52,500 |

| 1851 | 3,600 | 1,100 | 1,500 | 6,200 |

| 1852 | 10,000 | 50,000 | 10,000 | 70,000 |

| 1853 | 7,500 | 20,000 | 8,000 | 35,500 |

| 1854 | 6,000 | 12,000 | 3,200 | 21,200 |

| 1855 | 500 | 1,500 | 4,700 | 6,700 |

| 1856 | 1,000 | 8,000 | 2,400 | 11,400 |

| 1857 | 1,500 | 4,000 | 1,300 | 6,800 |

| 1858 | 1,500 | 6,000 | 150 | 7,650 |

| 1859 | 2,000 | 17,000 | 1,400 | 20,400 |

| 1860 | 1,500 | 9,000 | 1,600 | 12,100 |

| Total | 53,000 | 200,300 | 43,000 | 296,300 |

| 1834–60 | Oregon | California | Utah | Total |

Records of early trail travel are not complete. Emigration to California greatly increased with the 1849 gold rush. California remained the top destination until 1860. Almost 200,000 people went there between 1849 and 1860.

Travel slowed after 1860 due to the Civil War. Many people on the trail from 1861–1863 were escaping the war. Gold and silver discoveries in other Western states also increased trail use. Mormon emigration records after 1860 are more accurate.

The trip was hard and dangerous. About 3 to 10 percent of emigrants may have died on the way. Many who went were young, between 12 and 24 years old.

Costs of the Journey

The cost of traveling the Oregon Trail varied. It could be free or a few hundred dollars per person. The cheapest way was to work as a driver. People with money could buy livestock in the Midwest and sell them for profit in the West.

About 60 to 80 percent of travelers were farmers. They already owned a wagon and livestock. This lowered their cost to about $50 per person for food. Families planned for months and made many items themselves. Individuals buying everything might spend $150–200 per person. Later, ferries and toll roads added about $30 per wagon.

Deaths on the Trail

| Cause | Estimated deaths |

|---|---|

| Disease | 6,000–12,500 |

| Battling with Native Americans | 3,000–4,500 |

| Freezing | 300–500 |

| Scurvy | 300–500 |

| Run overs | 200–500 |

| Drownings | 200–500 |

| Shootings | 200–500 |

| Miscellaneous | 200–500 |

| Totals | 10,400–20,000 |

The exact number of deaths on the trail is not known. People often buried bodies in unmarked graves to hide them from animals or Native Americans. Graves were sometimes placed in the middle of the trail and run over by wagons.

Disease was the biggest killer. Cholera killed up to 3 percent of all travelers from 1849 to 1855. It spread through contaminated water or food. Other common diseases included dysentery and typhoid fever. Airborne diseases like diphtheria and measles also affected travelers. Poor sanitation and no way to isolate the sick made diseases spread quickly.

Native American attacks increased after 1860. This was when many army troops were removed. Miners and ranchers moved onto Native American lands. New trails were developed to avoid dangerous areas.

Other causes of death included hypothermia (freezing), drowning in rivers, being run over by wagons, and accidental gun deaths. Few people knew how to swim back then. Being run over was a major cause of death, even though wagons moved slowly. People, especially children, often tried to get on and off moving wagons. Dresses could also get caught in wheels. Accidental shootings decreased as people became more familiar with their weapons.

Many travelers suffered from scurvy by the end of their trips. Their diet of flour and salted meat lacked vitamin C. Some believe scurvy deaths may have been as common as cholera deaths.

Other deaths were from falling trees, flash floods, animal kicks, lightning, snake bites, and stampedes. One historian estimates a 4 percent death rate, or 16,000 out of 400,000 pioneers.

Reaching the Sierra Nevada before winter storms was crucial. The most famous failure was the Donner Party. They got stuck in the snow in November 1846. By April 1847, 33 people had died at Donner Lake.

Other Ways to Go West

Before railroads, there were other ways to get to California or Oregon.

The York Factory Express was an overland trade route used by the Hudson's Bay Company. It went from Fort Vancouver to Hudson Bay. This route was mostly abandoned after the Oregon Treaty of 1846.

The longest trip was by sailing ship around Cape Horn. This took four to seven months and cost $350 to $500. You could work as a crewman to travel for free.

Another route involved taking a ship to Colón, Panama (then Aspinwall). Then, a hard, disease-ridden trip by canoe and mule across the Isthmus of Panama. Finally, another ship from Panama City, Panama to Oregon or California. This trip could take less than two months. But catching a fatal disease was possible. The Panama Railroad was completed in 1855. This made the 50-mile (80 km) trip across the Isthmus much faster and safer.

Cornelius Vanderbilt set up a route across Nicaragua in 1849. It used steamships, small boats, and stagecoaches. Vanderbilt attracted many travelers by offering lower fares. But civil unrest in Nicaragua ended this project in 1855.

Some adventurous travelers took a ship to Mexico. Then they crossed the country and caught another ship from Acapulco. This route was not very popular.

The Gila Trail went through Arizona and across the Sonora Desert in California. This route was used by many gold miners in 1849. It was a winter crossing, despite its challenges.

The Butterfield Stage Line ran from 1857 to 1861. It delivered mail from St. Louis, Missouri, to San Francisco, California. The 2,800-mile (4,500 km) route went through Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico. It used 250 stagecoaches and 1,800 horses and mules. A one-way ticket cost $200. The trip took 25 to 28 days.

The ultimate competitor arrived in 1869. The first transcontinental railroad cut travel time to about seven days. It cost about $60 for an economy ticket.

Legacy of the Trail

One lasting impact of the Oregon Trail is the expansion of the United States to the West Coast. Without the thousands of American settlers, this might not have happened.

Arts, Entertainment, and Media

The Oregon Trail has inspired many creative works.

Commemorative Coin

The Oregon Trail Memorial half dollar was made to remember the route. It was issued from 1926 to 1939.

Music

The Oregon Trail is featured in many songs.

- "The Oregon Trail" was recorded by Tex Ritter in 1935.

- Woody Guthrie wrote and recorded a song called "Oregon Trail" in 1941. It is on his Columbia River Collection album.

Games

The story of the Oregon Trail inspired the educational video game series The Oregon Trail. This game was very popular in the 1980s and early 1990s.

In 2014, a musical called The Trail to Oregon! was performed. It was based on The Oregon Trail game.

Television

The Oregon Trail was a TV series in 1977. It starred Rod Taylor. The show was canceled after six episodes. But all 14 episodes were later released on DVD.

An episode of Teen Titans Go! called "Oregon Trail" makes fun of the expeditions and the video game.

Film

The 1930 Western film The Big Trail starred John Wayne. He played a fur trapper leading settlers across the Oregon Trail.

The 1967 film The Way West was based on a novel. It followed a wagon train in 1843.

The animated film Calamity, a Childhood of Martha Jane Cannary shows a wagon expedition to Oregon. It includes a young Calamity Jane.

Images for kids

-

The Central Route in Nevada.

See also

In Spanish: Senda de Oregón para niños

In Spanish: Senda de Oregón para niños