History of women in the United States facts for kids

The history of women in the United States is about the lives and important contributions of women throughout American history.

The first women in what is now the United States were Native Americans. In the 1800s, many women mostly stayed in roles at home. This was often due to Protestant beliefs. The fight for women's right to vote ended when the Nineteenth Amendment was added to the U.S. Constitution in 1920. During World War II, many women took jobs that men had left to fight overseas. Starting in the 1960s, the second-wave feminist movement changed how people thought about women. However, it did not succeed in passing the Equal Rights Amendment. In the 2000s, women have gained more important roles in American life.

Contents

- Colonial Times: Early American Women

- The 1800s: Growth and Change

- Sacagawea: A Famous Guide

- Midwestern Pioneers: Farm Life

- Reform Movements: Fighting for Change

- Education for Women

- Feminism: The First Wave Begins

- Women in Medicine

- Women in Industry

- Abolitionists: Fighting Slavery

- Civil War: Women's Contributions

- Postwar South: New Roles

- Settling the Great Plains: Farm Life

- Suffrage: The Fight for the Vote

- Domesticity and Home Life

- The Cult of Domesticity

- Jobs and Professions for Women

- Missionaries: Women Spreading Faith

- Settlement Houses: Helping Communities

- Nursing: A Growing Profession

- Progressive Era: Early 1900s Reforms

- Jane Addams: A Social Worker and Peace Advocate

- French Canadian Women in New England

- Midwest: Women's Work and Clubs

- South: Political Leaders and Challenges

- West: Progressive Women

- Suffrage: The Final Push

- Women's International Activity

- World War I: Women Step Up

- 19th Amendment: Women Get the Vote

- Black Women in the 1920s

- Feminism in the 1920s

- The Great Depression: Challenges and Achievements

- New Deal: Government Programs

- Since 1941: Modern Women's History

- World War II: Women in the Workforce

- Nursing in Wartime

- Volunteer Activities

- Baby Boom and Postwar Life

- Housewives After the War

- Women in Military Service

- Postwar: Return to Domesticity and New Advances

- Civil Rights: Fighting for Equality

- Women's Status in the 1950s and 1960s

- Late 1960s: Feminist Actions

- 1970s: Legal Victories and Setbacks

- The Radical Feminist Movement

- Firsts in the 1970s

- 1970s: More Legal Gains

- 2000–2016: New Milestones

- Trump Presidency: 2016–2020

Colonial Times: Early American Women

Women's lives in the early American colonies were different depending on the colony. Most British settlers came from England and Wales. Families often settled together in New England. In the Southern colonies, families usually settled on their own. Many Dutch and Swedish settlers also came to America.

After 1700, most new people came as indentured servants. These were young, single men and women looking for a new life. After the 1660s, many black slaves arrived, mostly from the Caribbean. Food was much easier to find than in Europe. There was also plenty of fertile land for farming families. However, diseases like malaria were common in the South. Many new arrivals died within five years. Children born in America were usually safe from the deadly forms of malaria.

The first English people to arrive in America were from the Roanoke Colony in July 1587. There were 17 women, 91 men, and 9 boys. On August 18, 1587, Virginia Dare was born. She was the first English child born in what became the United States. Her mother was Eleanor Dare, the daughter of the colony's governor. No one knows what happened to the Roanoke colonists. They were likely attacked by Native Americans. Those who survived probably joined local tribes.

Virginia: First English Settlement

Jamestown was the first English settlement in America. It was started in 1607 in what is now Virginia. In 1608, the first English women arrived in Jamestown. They were Mistress Forrest and her maid Anne Burras. Anne Burras was the first English woman to marry in the New World. Her daughter, Virginia Laydon, was the first child of English colonists born in Jamestown.

In 1619, the first Africans arrived in Jamestown. There were about twenty people, including at least one woman. They were taken from the Kingdom of Ndongo in modern Angola. They had been on a Portuguese slave ship that was attacked by English privateers. Their arrival marked the start of slavery and African-American history in British America.

Also in 1619, 90 young, single women from England came to Jamestown. They were meant to be wives for the men there. The women were "auctioned off" for 150 pounds of tobacco each. This covered the cost of their travel. These women were often called "tobacco brides". Many such trips brought women to America for this reason. The tobacco brides were promised free travel and a trousseau (a collection of clothes and linens) for their journey.

New England: Puritan Life

In New England, the Puritan settlers from England brought their strong religious beliefs. They also brought a very organized way of life. They believed women should focus on raising children who respected God.

How women were treated differed among ethnic groups. Among Puritans, wives almost never worked in the fields with their husbands. But in German communities in Pennsylvania, many women worked in fields and stables. German and Dutch immigrants gave women more control over property. This was not allowed under English law. Unlike English colonial wives, German and Dutch wives owned their own clothes and other items. They could also write wills for property they brought into the marriage.

The New England economy grew quickly in the 1600s. This was due to many new people arriving, high birth rates, low death rates, and lots of cheap farmland. The population grew from 3,000 in 1630 to 91,000 in 1700. Between 1630 and 1643, about 20,000 Puritans arrived. They mostly settled near Boston. After 1643, fewer than 50 immigrants came each year. Families had an average of 7.1 children between 1660 and 1700.

Economic growth helped everyone, even farm laborers. The growing population led to less good farmland. This caused people to marry later or move west. In towns, new jobs opened for women, like weaving, teaching, and tailoring. The region was near New France, which used Native American warriors to attack villages. Women were sometimes captured. The British government spent a lot of money during the French and Indian Wars. This helped the economy grow.

Schooling for Girls

Schools supported by taxes for girls started in New England as early as 1767. It was not always easy to get towns to agree. For example, Northampton, Massachusetts, was slow to adopt it. Rich families there did not want to pay taxes for poor families' education. Northampton taxed all households to support a grammar school for boys going to college. Girls were not educated with public money until after 1800. In contrast, Sutton, Massachusetts, had diverse leaders and religions. Sutton paid for schools by taxing only households with children. This led to support for education for both boys and girls.

Historians note that reading and writing were different skills back then. Schools taught both. But in places without schools, reading was mainly taught to boys. Only a few privileged girls learned to read. Men needed to read and write for their work. Girls mainly needed to read religious materials. This is why colonial women could often read but not write. They would use an "X" to sign their names.

Hispanic New Mexico: Family Life

Hispanic women were very important in traditional family life in the Spanish colonies of New Mexico. Their descendants are a large part of the population in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado.

Important Colonial Women

Pocahontas: A Native American Story

Pocahontas is a famous Native American woman. She was the daughter of Chief Powhatan in Virginia. John Smith said she saved him from death in 1607. However, some doubt if this really happened. Colonists took her hostage in 1612 when she was 17. She became a Christian and married planter John Rolfe in 1614. This was the first recorded interracial marriage in American history. This marriage brought peace between the colonists and the Native Americans. She and Rolfe went to England in 1616. She was presented at the court of King James I. She died soon after. Many leading families in Virginia today proudly say she is their ancestor. Pocahontas quickly became part of early American stories. She represents myths, culture, and historical events.

Cecily Jordan Farrar: A Jamestown Settler

Cecily Jordan Farrar was an early woman settler in colonial Jamestown. She came as a child in 1610. She became one of the few female "ancient planters" (early settlers who received land). She married Samuel Jordan before 1620. After Samuel died in 1623, Cecily became a head of household at Jordan’s Journey. That same year, she was involved in the first "breach of promise" lawsuit in English North America. This happened when she chose to marry William Farrar instead of Grivell Pooley.

Mayflower Women

On November 21, 1620, the Mayflower arrived in what is now Provincetown, Massachusetts. It brought the Puritan pilgrims. There were 102 people aboard. This included 18 married women, seven unmarried women with parents, three young unmarried women, one girl, and 73 men. Three-fourths of the women died in the first few months. While the men built homes, the women stayed in the damp, crowded ship. By the first Thanksgiving in autumn 1621, only four women from the Mayflower were still alive.

Anne Hutchinson: A Religious Leader

In the 1630s, Anne Hutchinson (1591–1643) started holding religious meetings at her home. Many people, including important men, attended. Hutchinson's influence was so strong that it worried the church leaders. This was clear when some of her male supporters refused to join the militia to fight Pequot natives. The authorities, led by Governor John Winthrop, first banished her brother-in-law. Hutchinson herself was put on trial in late 1637 and also banished. She was allowed to stay under house arrest until winter ended. In March 1638, she was formally removed from the church. She and her children joined her husband in the new colony of Rhode Island. In 1660, Mary Dyer, a Quaker who followed Hutchinson, was executed in Massachusetts. This was for repeatedly returning to Massachusetts and sharing Quaker beliefs.

Enslaved Women's Fight for Freedom

In 1655, Elizabeth Key Grinstead, an enslaved woman in Virginia, won her freedom in a lawsuit. She argued that her father was a free Englishman. Her mother was enslaved, and her father was her mother's owner. It also helped that her father had baptized her as a Christian. However, in 1662, Virginia passed a law. It stated that any child born in the colony would have the same status as its mother, whether slave or free. This changed an old English law where a child's status followed the father. It allowed white men to hide mixed-race children and avoid supporting or freeing them.

When Europeans came to the New World, many Native Americans converted to Christianity. This made religion less important for telling people apart. Skin color became more important.

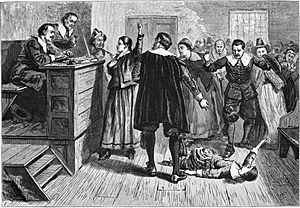

Witches in Salem Village

In the small Puritan community of Salem Village, Massachusetts, the Salem witch trials began in 1692. They started when a group of girls met at Reverend Parris's home. They listened to stories from his slave, Tituba. They also played fortune-telling games, which Puritans strictly forbid. The girls began acting strangely. This led the community to think they were victims of witchcraft. The girls accused three women: Tituba, Sarah Good, and Sarah Osbourne. Tituba confessed to seeing the devil and said there was a group of witches in Salem Village. The other two women said they were innocent. But they were found guilty of witchcraft after a formal trial.

The accused girls then named other townspeople as witches. By the end of the trials in 1693, 24 people had died. Some died in jail, but 19 were executed. Some accused people confessed to being witches. However, only those who said they were innocent were executed.

Salem was the start of witchcraft scares in 24 other Puritan communities. These episodes were shorter and less dramatic. They usually involved only one or two people. Most were older women, often widowed or single. They often had a history of arguments with neighbors. In October 1692, the governor of Massachusetts stopped the court cases. He limited new arrests and ended the witch hunts.

Life as a Housewife

A "Housewife" (or "Goodwife" in New England) described a married woman's role in the economy and culture. Under laws called "coverture," a wife had no separate legal identity. Everything she did was under her husband's control. He controlled all the money, even any dowry or inheritance she brought to the marriage. She did have certain legal rights to family property when her husband died. She was in charge of feeding, cleaning, and medical care for everyone in the home. She also supervised servants. A housewife's duties included managing cellars, pantries, and wash houses. She was responsible for making clothes, candles, and food at home.

During harvest, she helped the men gather crops. She usually kept a vegetable garden and cared for poultry and milked cows. The husband handled other livestock and dogs. Mothers were responsible for their children's spiritual and civic well-being. Good housewives raised good children who would become respected citizens. Laws and society allowed husbands to use physical power over their wives, which could lead to violence. A few housewives were able to file for divorce.

Women Writers

In 1650, Anne Dudley Bradstreet became America's first published poet. Her book, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung up in America, was published in London that same year. This made Bradstreet the first female poet published in both England and the New World. Bradstreet believed the family was where people and communities formed their identities. She saw education happening within the family, not just in schools.

The earliest known work by an African American and a slave was Lucy Terry's poem "Bars Fight." It was written in 1746 and first published in 1855. The poem describes a violent event between settlers and Native Americans in Deerfield, Massachusetts. Former slave Phillis Wheatley became famous in 1770. She wrote a poem about the death of preacher George Whitefield. In 1773, 39 of Phillis Wheatley's poems were published in London as a book. It was called Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. This was the first published book by an African American.

One Woman's Vote

In 1756, Lydia Chapin Taft of Uxbridge, Massachusetts became the only colonial woman known to vote. She cast a vote in a local town hall meeting for her deceased husband. From 1775 to 1807, New Jersey's state constitution allowed all people worth fifty pounds who lived in the state for one year to vote. This included free black people and single women. Married women could not vote because their property ownership was limited.

The Great Awakening: Religious Revival

In the 1740s, religious leaders started a revival called the First Great Awakening. It energized Protestants in the 13 colonies. This movement was known for strong emotions and a belief in equality. It split several churches into old and new groups. They gained many members among white farmers. Women were especially active in the Methodist and Baptist churches that were growing everywhere. Women were rarely allowed to preach. However, they had a voice and a vote in church matters. They were very interested in watching the moral behavior of church members. The Awakening led many women to think deeply about their lives. Some kept diaries or wrote memoirs. The autobiography of Hannah Heaton (1721–94), a farm wife from Connecticut, tells about her experiences. It describes her encounters with Satan, her spiritual growth, and farm life.

Religious leaders worked hard to convert enslaved people to Christianity. They were very successful among black women. These women had been religious leaders in Africa and continued this role in America. Enslaved women provided spiritual guidance in healing, church rules, and religious excitement.

American Revolution: Women's Roles Change

Leading up to the Revolution

In the mid-1700s, women in colonies like Virginia and Maryland played a big role in public life through printed materials. Women's voices spread through books, newspapers, and almanacs. Some women writers sought equal treatment under the law. They became involved in public debates even before the Stamp Act in 1765.

After 1765, Americans protested British policies by boycotting imported British goods. Women actively encouraged these boycotts. They refused to buy imports. They also promoted using homemade clothing and other local products.

Impact of the Revolution

The American Revolution deeply changed American society's ideas. One big change was in the roles of women. The idea of "republican motherhood" was born during this time. It showed the importance of Republicanism in America. This idea meant that a successful republic needed good citizens. So, women had the key role of teaching their children values that would help the republic. During this period, the relationship between a wife and husband also became more open. Love and affection, instead of just obedience, became the ideal for marriage. Many women also helped the war effort by raising money and running family businesses while their husbands were away.

Despite these gains, women were still legally and socially under their husbands' control. They could not vote. Their main role was still seen as mothers.

Deborah Sampson was the only woman historians know of who fought disguised as a man in the Revolutionary War. In 1782, she joined the 4th Massachusetts Regiment. When her gender was found out, she was honorably discharged. Many women helped the Army by cooking and cleaning for their husbands. In 1776, Margaret Corbin fired her husband's cannon after he was killed. She was badly wounded. She received a pension from Congress for her service. This made her the first American woman to get a government pension. At the Battle of Monmouth in 1778, Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley fired her husband's cannon after he was hurt. Her story became the "Molly Pitcher" legend.

In March 1776, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband John Adams, a leader in the Continental Congress. She asked him to "remember the ladies" in the new laws. She wanted them to be "more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors." She also asked him not to give husbands "unlimited power." Her husband wrote back, "As to your extraordinary code of laws, I cannot but laugh...Depend upon it, we know better than to repeal our masculine systems."

The Revolution started a debate about women's rights. It also created a good environment for women to be involved in politics. Women took a small but visible role in public life after 1783. First Lady Martha Washington hosted social events in the capital. This "Republican Court" allowed important women to play a behind-the-scenes political role. This reached a peak in the Petticoat affair of 1830. In this event, the wives of President Andrew Jackson's cabinet members embarrassed the wife of the Secretary of War. This led to a political crisis for the president.

However, these new possibilities also caused a backlash. This actually set back women's rights. It led to stricter rules that kept women out of political life.

Quaker Women's Equality

Quakers were strong in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. They believed in equal roles for women. They thought all humans, regardless of sex, had the same "Inner light". Quakers like John Dickinson and Thomas Mifflin were among the Founding Fathers.

The 1800s: Growth and Change

Sacagawea: A Famous Guide

Sacagawea (1788–1812) was a well-known Native American woman after Pocahontas. She went with the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806) to the Pacific coast and back. The captains hired her husband, a fur trapper, as an interpreter. Sacagawea came along to interpret the Shoshone language. She was only about 16 and had a son during the trip. Her role has been greatly exaggerated. This is partly because writers wanted to use her to support the idea of Manifest Destiny.

Midwestern Pioneers: Farm Life

Clear gender roles existed among farm families settling in the Midwest between 1800 and 1840. Men were the providers. They thought about how profitable farming would be in a certain area. They worked hard to support their families. Men mostly spoke about public matters, like voting and handling money. During the move west, women's diaries showed little interest in money problems. They were very concerned about being separated from family and friends. Women also faced physical challenges. They were expected to have babies, do housework, care for the sick, and manage garden crops and poultry. Outside German American communities, women rarely worked in the fields. Women created neighborhood social groups. These often involved church or quilting parties. They shared information and tips on raising children. They also helped each other during childbirth.

Reform Movements: Fighting for Change

Many women in the 1800s joined reform movements. They were especially active in abolitionism, the movement to end slavery.

In 1831, Maria W. Stewart (an African-American woman) began writing essays and giving speeches against slavery. She promoted education and economic independence for African Americans. Stewart was the first woman of any race to speak publicly on political issues. She gave her last public speech in 1833. She then worked in women's organizations. Her short career paved the way for other African-American women speakers. These included Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Sojourner Truth, and Harriet Tubman. Since direct public involvement was difficult and dangerous, many women helped the movement by boycotting goods made by slaves. They also organized fairs and food sales to raise money.

For example, Pennsylvania Hall was the site of the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in 1838. Three thousand white and black women gathered to hear abolitionists like Maria Weston Chapman. But a mob outside drowned out the speakers. When the women left, linking arms, they were insulted. The next day, the mob returned and burned the hall down. It had only opened three days earlier.

The Grimké sisters from South Carolina (Angelina and Sarah Grimké) faced much abuse for their abolitionist work. They traveled throughout the North, lecturing about their experiences with slavery on their family plantation.

Many women's anti-slavery societies were active before the Civil War. The first was created in 1832 by free black women from Salem, Massachusetts. The strong abolitionist Abby Kelley Foster also led Lucy Stone and Susan B. Anthony into the anti-slavery movement.

Education for Women

In 1821, Emma Willard founded the Troy Female Seminary in Troy, New York. This was the first American school to offer young women a pre-college education equal to that given to young men. Students at this private school were taught subjects usually for males. These included algebra, anatomy, natural philosophy, and geography.

Mary Lyon (1797–1849) founded Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in 1837. It was the first college opened for women. It is now Mount Holyoke College, one of the Seven Sisters colleges. Lyon was a deeply religious Congregationalist. She preached revivals at her school. She admired colonial theologian Jonathan Edwards for his ideas of self-control and kindness. Georgia Female College, now Wesleyan College, opened in 1839. It was the first Southern college for women.

Oberlin College opened in 1833. In 1837, it became the first coeducational college by admitting four women. Soon, women were fully part of the college. They made up one-third to half of the students. The religious founders, especially Charles Grandison Finney, believed women were naturally more moral than men. Many female graduates, inspired by this idea, became missionaries. Historians often see coeducation at Oberlin as an important step toward equality for women in higher education.

More women enrolled in higher education after the Civil War. In 1870, 8,300 women made up 21% of all college students. In 1930, 480,000 women made up 44% of the student body.

| College women enrollment |

Women's colleges | Coed-colleges | % of all students |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 6,500 | 2,600 | 21% |

| 1890 | 16,800 | 39,500 | 36% |

| 1910 | 34,100 | 106,500 | 40% |

| 1930 | 82,100 | 398,700 | 44% |

| Source: |

Feminism: The First Wave Begins

Judith Sargent Murray published an important essay in 1790 called On the Equality of the Sexes. She blamed poor education for women's problems. However, scandals around the lives of English writers Catharine Macaulay and Mary Wollstonecraft made feminist writing more private from the 1790s to the early 1800s. Feminist essays by John Neal in the 1820s helped bring feminism back into the American mainstream. His support was important because he was a male writer, so he was less attacked than female feminist thinkers.

The 1848 Seneca Falls Convention is often seen as the start of the first wave of feminism. It was inspired by an event in 1840. Elizabeth Cady Stanton met Lucretia Mott at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. The conference refused to let Mott and other women delegates from America sit because they were women. Stanton, a young bride, and Mott, a Quaker preacher, then talked about holding a convention for women's rights.

About 300 women and men attended the Convention. Famous people like Lucretia Mott and Frederick Douglass were there. At the end, 68 women and 32 men signed the "Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions". Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the M'Clintock family wrote it.

The "Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions" was written like the "Declaration of Independence." For example, it said, "We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men and women are created equal and endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights." It also stated, "The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man towards woman."

The declaration listed women's complaints. These included laws that denied married women control over their wages, money, and property. All of these had to be given to their husbands under "coverture laws." It also mentioned women's lack of access to education and professional careers. It spoke about the low status given to women in most churches. The Declaration also said that women should have the right to vote.

Two weeks later, some participants organized the Rochester Women's Rights Convention of 1848 in Rochester, New York. This convention elected Abigail Bush as its president. This made it the first public meeting with both men and women in the U.S. to choose a woman as its leader. Other conventions followed in Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York. The first National Women's Rights Convention was held in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1850. Women's rights conventions were held regularly until the Civil War began.

Women in Medicine

In 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910) graduated from Geneva Medical College in New York. She was at the top of her class. This made her the first female doctor in America. In 1857, she, her sister Emily, and Marie Elisabeth Zakrzewska (1829–1902) founded the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. This was the first American hospital run by women. It was also the first dedicated to serving women and children.

Women in Industry

The fast growth of textile manufacturing in New England from 1815 to 1860 led to a worker shortage. Mill owners hired recruiters to find young women. Between 1830 and 1850, thousands of single farm women moved from rural areas to mill villages. They worked to help their families, save for marriage, and broaden their experiences. As the textile industry grew, so did immigration. By the 1850s, mill owners replaced Yankee girls with immigrants, especially Irish and French Canadians.

Abolitionists: Fighting Slavery

Women continued to be active in reform movements in the second half of the 1800s. In 1851, former slave Sojourner Truth gave a famous speech called "Ain't I a Woman?" at the Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio. In this speech, she spoke against the idea that women were too weak for equal rights. She shared the hardships she had faced as a slave. In 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote the anti-slavery book Uncle Tom's Cabin. The book focused public attention on slavery. It was very controversial for its strong anti-slavery message. Stowe used her own experiences to write the book. She was familiar with slavery and the Underground Railroad. Uncle Tom's Cabin was a bestseller. It sold 10,000 copies in the U.S. in its first week and 300,000 in the first year. In Great Britain, it sold 1.5 million copies in one year. After the book was published, Harriet Beecher Stowe became famous. She spoke against slavery in America and Europe.

Before the Civil War, Harriet Tubman, a runaway slave, freed over 70 slaves. She did this through 13 secret rescue missions to the South. In June 1863, Harriet Tubman became the first woman to plan and lead an armed expedition in U.S. history. She advised Colonel James Montgomery and his 300 soldiers. Tubman led them on a raid in South Carolina. They freed about 800 slaves.

Civil War: Women's Contributions

Women in the Union (North)

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), Dorothea Dix was the Union's Superintendent of Female Nurses. She was in charge of over 3,000 female nurses in army hospitals. Women provided care to Union and Confederate troops in field hospitals and on the Union Hospital Ship Red Rover. Dr. Mary Edwards Walker served as an assistant surgeon with Union forces. She was imprisoned as a spy in Richmond. After the war, President Andrew Johnson gave her the Medal of Honor. This made her the only woman to receive the highest U.S. military honor. About 400 to 750 women soldiers served in disguise.

Women in the Confederacy (South)

Southern women strongly supported their men going to war. They saw men as protectors. They believed in the romantic idea of men fighting for their country, family, and way of life. Mothers and wives kept in touch with their loved ones by writing letters. African American women, however, had seen their families broken up for generations. They faced this issue again at the start of the war.

By summer 1861, the Union naval blockade stopped cotton exports and imported goods. Food that used to come by land was cut off. Women had to manage with what they had. They bought less, used old spinning wheels, and grew more peas and peanuts in their gardens. This helped provide clothes and food. They used substitutes when possible. Households were badly hurt by rising prices and shortages of food, animal feed, and medical supplies. The Georgia legislature set limits on cotton growing. But food shortages worsened, especially in towns.

The overall drop in food supplies, made worse by the failing transportation system, led to serious shortages and high prices in cities. When bacon cost a dollar a pound in 1863, poor women in Richmond, Atlanta, and other cities rioted. They broke into shops and warehouses to take food. The women were angry about ineffective state aid, speculators, merchants, and planters. As wives and widows of soldiers, they were hurt by the poor welfare system.

Postwar South: New Roles

About 250,000 Southern soldiers did not return home. This was 30% of all white men aged 18 to 40 in 1860. Widows often left their farms and moved in with relatives. Some became refugees in camps with high rates of disease and death. In the Old South, being an "old maid" was embarrassing. Now, it became almost normal. Some women welcomed the freedom of not having to marry. Divorce, though not fully accepted, became more common. The idea of the "New Woman" appeared. She was self-sufficient, independent, and different from the "Southern Belle" of earlier times.

The work of wealthy white women changed greatly after the Civil War. Women over 50 changed the least. They insisted on having servants and continued their traditional management roles. The next generation, young wives and mothers during the Civil War, relied less on black servants. They were more flexible with housework. The youngest generation, who grew up during the war and Reconstruction, did many of their own chores. Some sought paid jobs outside the home, especially in teaching. This allowed them to escape domestic chores and forced marriage.

Settling the Great Plains: Farm Life

Railroads arrived in the 1870s. This opened up the Great Plains for settlement. Now, wheat and other crops could be shipped cheaply to cities in the East and Europe. Immigrants poured in, especially from Germany and Scandinavia. On the plains, few single men tried to farm or ranch alone. They knew they needed a hard-working wife and many children. Women handled chores like raising children, feeding and clothing the family, managing the house, feeding hired workers, and, after the 1930s, handling paperwork and finances. In the early years of settlement, farm women played a key role in family survival by working outdoors. After a generation, women increasingly left the fields. This changed their roles within the family. New tools like sewing and washing machines encouraged women to focus on domestic roles. The scientific housekeeping movement promoted home cooking and canning. Farm papers had advice columns for women. Home economics courses were taught in schools.

People in the East often thought farm life on the prairies was lonely. But farmers and their wives created a rich social life. They often had activities that combined work, food, and fun. These included barn raisings, corn huskings, quilting bees, Grange meetings, church events, and school functions. Women organized shared meals and potlucks. They also had long visits between families. The Grange was a national farmers' organization. It reserved high positions for women. It gave them a voice in public affairs and promoted equality and voting rights.

Suffrage: The Fight for the Vote

The women's suffrage movement began with the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention. Many activists became politically aware during the abolitionist movement. The movement reorganized after the Civil War. It gained experienced campaigners, many of whom had worked for prohibition in the Women's Christian Temperance Union. By the end of the 1800s, a few western states had given women full voting rights. Women also won important legal victories, gaining rights in areas like property and child custody.

In 1866, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony formed the American Equal Rights Association. This group worked for voting rights for all, white and black, women and men. In 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment was passed. This was the first amendment to say that voters were "male." In 1869, the women's rights movement split into two groups. This was due to disagreements over the Fourteenth and soon-to-be-passed Fifteenth Amendments. The two groups did not reunite until 1890. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony formed the more radical National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in New York. Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe organized the more conservative American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) in Boston. In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment gave black men the right to vote. The NWSA refused to support it. They argued for a Sixteenth Amendment that would give everyone the right to vote. Frederick Douglass disagreed with Stanton and Anthony on this.

In 1869, Wyoming became the first territory or state in America to grant women the right to vote. In 1870, Louisa Ann Swain became the first woman in the United States to vote in a general election. She cast her ballot on September 6, 1870, in Laramie, Wyoming.

From 1870 to 1875, several women tried to use the Fourteenth Amendment in court to get the right to vote or practice law. These included Virginia Louisa Minor, Victoria Woodhull, and Myra Bradwell. But they were all unsuccessful. In 1872, Susan B. Anthony was arrested and tried in Rochester, New York. She tried to vote for Ulysses S. Grant in the presidential election. She was found guilty and fined $100. She refused to pay. At the same time, Sojourner Truth appeared at a polling place in Battle Creek, Michigan. She demanded a ballot but was turned away. Also in 1872, Victoria Woodhull became the first woman to run for President. She could not vote and only received a few votes. She lost to Ulysses S. Grant. The Equal Rights Party nominated her. She supported an 8-hour workday, a graduated income tax, social welfare programs, and profit sharing. Victoria Woodhull fought for women's rights. She advocated for the right to marriage, divorce, and childbirth. She also fought against the double standards for men and women.

In 1874, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was founded by Annie Wittenmyer. It worked to ban alcohol. With Frances Willard as its head (starting in 1876), the WCTU also became important in the fight for women's voting rights. In 1878, a woman suffrage amendment was first introduced in the U.S. Congress, but it did not pass.

Domesticity and Home Life

Kristin Hoganson's essay "Cosmopolitan Domesticity" talks about how middle-class American women, as homemakers, were part of international relations from 1865 to 1920. After the Civil War, there was a boom in interior design writing. Many suggested using foreign styles in homes. Interior design in middle-class houses was seen as a way to express oneself. A popular design book said, "We judge her [a woman’s] temperament, her habits, her inclinations, by the interior of her home." Before the war, foreign styles were usually limited to European fashions. But in the second half of the century, objects were imported from further away. Women wanted to show their status through fancy home designs. The growing U.S. foreign policy after the Civil War increased interest in cosmopolitan interior design. This was because travel writings, photos, and missionary exhibits made Americans more aware of other places. Tourists, missionaries, and business people also brought foreign goods and ideas to America.

The Cult of Domesticity

The "Cult of Domesticity" was a new idea of womanhood. It came from the fact that 19th-century middle-class families did not have to make everything they needed to survive. Men could now work in jobs that produced goods or services. Their wives and children stayed at home. The ideal woman became one who stayed at home and taught children how to be good citizens. American Cookery, written in 1796 by Amelia Simmons, was the first cookbook by an American. It was popular and had many editions.

The idea of honor in the pre-Civil War South was linked to women's social status and Southern religious beliefs. There were no strict gender lines where women only focused on religion and men only on honor. Women felt subject to ideas of honor related to family structure, social class, and virtue. The different roles of Southern men and women affected masculine and feminine honor. This also affected the moral authority women had over men.

Jobs and Professions for Women

Many young women worked as servants or in shops and factories until they married. Then, they usually became full-time housewives. However, black, Irish, and Swedish adult women often worked as servants. After 1860, as larger cities opened department stores, middle-class women did most of the shopping. Young middle-class women clerks increasingly served them. Most young women typically quit their jobs when they married. In some ethnic groups, however, married women were encouraged to work. This was especially true among African-Americans and Irish Catholics. When the husband ran a small shop or restaurant, wives and other family members could work there. Widows and wives whose husbands left them often ran boarding houses.

Few women had careers. Teaching had once been mostly for men. But as schooling grew, many women became teachers. If they stayed unmarried, they could have a respected, though low-paying, lifelong career. At the end of this period, nursing schools opened new chances for women. But medical schools remained almost all male.

Business opportunities were very rare. A widow might take over her late husband's small business. However, the quick acceptance of the sewing machine made housewives more productive. It also opened new careers for women running their own small hat-making and dressmaking shops.

American women achieved several firsts in professions in the late 1800s. In 1866, Lucy Hobbs Taylor became the first American woman to get a dentistry degree. In 1878, Mary L. Page became the first woman in America to earn an architecture degree. She graduated from the University of Illinois. In 1879, Belva Lockwood became the first woman allowed to argue before the Supreme Court. The first case she argued was Kaiser v. Stickney in 1880. Arabella Mansfield had become America's first female lawyer in 1869. In 1891, Marie Owens was hired in Chicago as America's first female police officer. Because women were more involved in law, the first state laws making wife beating illegal were passed in 1871. However, these laws did not spread to all states or were not well enforced. One of the first female photojournalists, Sadie Kneller Miller, used her initials, SKM, as a byline to hide her gender. She covered sports, disasters, and diseases. She was recognized as the first female war correspondent.

Missionaries: Women Spreading Faith

By the 1860s, most large Protestant churches created missionary roles for women beyond being a male missionary's wife.

European Catholic women, as religious sisters, worked in immigrant communities in American cities. Mother Cabrini (1850–1917) founded the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Italy in 1880. She moved to New York in 1889. The orphanages, schools, and hospitals built by her order greatly helped Italian immigrants. She became a saint in 1946.

Settlement Houses: Helping Communities

In 1889, Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr opened the first settlement house in America. A settlement house is a center in a poor area that provides community services. Their house, called Hull House, was in a rundown mansion in a poor immigrant neighborhood in Chicago. Hull House offered many activities and services. These included health and child care, clubs for children and adults, an art gallery, a kitchen, a gym, a music school, a theater, a library, an employment office, and a labor museum. By 1910, 400 settlement houses had been started in America. Most of the workers in settlement houses were women.

Nursing: A Growing Profession

During the Spanish–American War (1898), thousands of U.S. soldiers got sick with typhoid, malaria, and yellow fever. The Army Medical Department could not handle it. So, Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee suggested that the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) choose qualified nurses to work for the U.S. Army. Before the war ended, 1,500 civilian nurses were sent to Army hospitals in the U.S., Hawaii, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. They also served on the hospital ship Relief. Twenty nurses died. The Army appointed Dr. McGee as Acting Assistant Surgeon General. This made her the first woman to hold that position. The Army was impressed by the nurses. Dr. McGee wrote a law to create a permanent group of Army nurses.

Progressive Era: Early 1900s Reforms

Across the nation, middle-class women organized for social reforms during the Progressive Era. They were especially concerned with banning alcohol, voting rights, school issues, and public health. Historian Paige Meltzer studied the General Federation of Women's Clubs. This was a national group of middle-class women who formed local clubs. Meltzer says these women's clubs used traditional ideas of womanhood to justify their involvement in community affairs. As "municipal housekeepers," they would clean up politics and cities. They would also look after their neighbors' health. Using their "maternal" skills, female activists investigated community needs. They used their expertise to push for and create a place for themselves in new government welfare programs. A good example is clubwoman Julia Lathrop's leadership in the Children's Bureau. The General Federation supported causes like pure food and drug laws, public health care for mothers and children, and a ban on child labor. They looked to the government to help achieve their vision of social justice.

Jane Addams: A Social Worker and Peace Advocate

One important woman of the Progressive Era was Jane Addams (1860–1935). She was a pioneer social worker. She led community activists at Hull House in Chicago. She was also a public thinker, writer, and speaker for voting rights and world peace. Along with presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, she was a leading reformer of the Progressive Era. She helped the nation focus on issues important to mothers. These included children's needs, public health, and world peace. She said that if women were to clean up their communities, they needed the right to vote to be effective. Addams became a role model for middle-class women who volunteered to improve their communities. In 1931, she became the first American woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

French Canadian Women in New England

French Canadian women saw New England as a place of opportunity. They could create new economic choices for themselves. These were different from the farming life in Quebec. By the early 1900s, some saw moving temporarily to the U.S. for work as a way to grow and become independent. Most moved permanently to the U.S. They used the cheap railroad system to visit Quebec sometimes. When these women married, they had fewer children and longer gaps between children than women in Canada. Some women never married. Stories suggest that being self-reliant and financially independent were important reasons for choosing work over marriage and motherhood. These women followed traditional gender roles to keep their "Canadienne" culture. But they also changed these roles to gain more independence as wives and mothers.

Midwest: Women's Work and Clubs

Most young urban women took jobs before marriage, then quit. Before high schools grew after 1900, most women left school around age fifteen after eighth grade. The type of work they did depended on their background and marital status. African-American mothers often chose day labor, usually as domestic servants. This gave them flexibility. Most mothers receiving pensions were white and only worked when necessary.

Across the region, middle-class women formed many new and expanded charity and professional groups. They pushed for mothers' pensions and more social welfare. Many Protestant homemakers were also active in the temperance and suffrage movements. In Detroit, the Federation of Women's Clubs (DFWC) promoted many activities for civic-minded middle-class women. These women followed traditional gender roles. The Federation argued that safety and health issues were most important to mothers. They believed these could only be solved by improving city conditions outside the home. The Federation pressured Detroit officials to improve schools, water, and sanitation. They also pushed for safe food handling and traffic safety. However, the members were divided on going beyond these issues or working with ethnic groups or labor unions. Their refusal to push traditional gender boundaries gave them a conservative reputation among the working class. Before the 1930s, women's groups in labor unions were too small to fill this gap.

South: Political Leaders and Challenges

Rebecca Latimer Felton (1835–1930) was a leading woman in Georgia. She was born into a rich plantation family. She married an active politician, managed his career, and became a political expert. She was an outspoken feminist. She led the prohibition and woman's suffrage movements. She fought for prison reform and held leadership roles in many reform groups. In 1922, she was appointed to the U.S. Senate. She was sworn in on November 21, 1922, and served one day. She was the first woman to serve in the Senate.

Middle-class urban women strongly supported voting rights. However, rural areas of the South were against it. State legislatures ignored efforts to let women vote in local elections. Georgia refused to ratify the federal 19th Amendment. It was proud to be the first to reject it. The Amendment passed nationally, and Georgia women gained the right to vote in 1920. However, black women and men still faced many barriers to voting until the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The women's reform movement grew in cities. But the South was mostly rural before 1945. In Dallas, Texas, women reformers helped build the city's social structure. They focused on families, schools, and churches in the city's early days. Many groups that created a modern city were founded and led by middle-class women. Through volunteer groups and clubs, they connected their city to national cultural and social trends. By the 1880s, women in temperance and suffrage movements changed the line between private and public life in Dallas. They pushed into politics for social issues.

From 1913–19, women's voting rights advocates in Dallas used national parties' education and advertising methods. They also used the lobbying tactics of women's clubs. They used popular culture, symbols, and traditional ideas. They adapted community festivals and social gatherings to persuade people politically. The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association based its campaign on social values and community standards. Community and social events were used to recruit for suffrage. This made the movement seem less radical.

Black female reformers usually worked separately. Juanita Craft was a leader in the Texas civil rights movement through the Dallas NAACP. She focused on working with black youth. She organized them to protest segregation in Texas.

West: Progressive Women

The Progressive movement was very strong in California. It aimed to clean up society's corruption. One way was to give voting rights to supposedly "pure" women in 1911. This was nine years before the 19th Amendment gave women the right to vote nationally in 1920. Women's clubs grew and focused on issues like public schools, pollution, and public health. California women were leaders in the temperance movement, moral reform, conservation, and recreation. Women did not often run for office. That was seen as getting their purity caught in political deals.

Suffrage: The Final Push

The campaign for women's voting rights gained speed in the 1910s. Women's groups won in western states and moved east. They left the conservative South for last. Parades were popular ways to get publicity. In 1916, Jeannette Rankin, a Republican from Montana, was elected to Congress. She became the first woman to serve in a high federal office. She was a lifelong pacifist. She was one of 50 members of Congress who voted against entering World War I in 1917. She was the only member of Congress who voted against declaring war on Japan after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Alice Paul led a small, active group. They sought arrest to highlight the unfairness of denying women the vote. After 1920, Paul spent 50 years leading the National Woman's Party. This group fought for her Equal Rights Amendment to ensure constitutional equality for women. It never passed. But she had great success with women being protected against discrimination by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. She insisted that her National Woman's Party focus only on the legal status of all women.

Women's International Activity

Women's support for international missionary work was highest from 1900 to 1930. The Great Depression caused a big cut in funding for missions. Mainstream churches generally shifted to supporting local missions.

Black women increased their role in international women's conferences and traveled abroad independently. Leaders like Ida B. Wells, Hallie Quinn Brown, and Mary Church Terrell spoke about American racial and gender discrimination when they traveled. The International Council of Women of the Darker Races brought together women of color. They worked to remove language, cultural, and regional barriers.

Peace Movement

Jane Addams was a famous peace activist. She founded the Woman's Peace Party in 1915. It was the American branch of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. Addams was its first president in 1915. She received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931.

World War I: Women Step Up

World War I was a total war. The nation mobilized its women to support the war effort at home and outside. All states organized women's committees. For example, North Carolina's women's state committee registered women for volunteer services. It promoted more food production and less wasteful cooking. It helped maintain social services. It worked to boost the morale of white and black soldiers. It improved public health and schools. It encouraged black participation in its programs. It also helped with the terrible Spanish flu epidemic in late 1918. The committee was generally successful in reaching middle-class white and black women. But it faced challenges from male lawmakers, limited money, and weak responses from farm women and working-class areas.

Women served in the military as nurses and in support roles. Tens of thousands worked in the U.S., and thousands more in France. The Army Nurse Corps (all female until 1955) was founded in 1901. The Navy Nurse Corps (all female until 1964) was founded in 1908. Nurses in both served overseas in military hospitals. During the war, 21,480 Army nurses served. Eighteen African-American Army nurses cared for German prisoners of war and African-American soldiers. Over 1,476 Navy nurses served. More than 400 military nurses died, mostly from the "Spanish Flu." In 1917, women could join the Navy for jobs other than nursing. They could be yeomen, electricians, and other roles. 13,000 women enlisted, mostly as yeomen (F) for female yeomen.

The Army hired 450 female telephone operators. They served overseas from March 1918 until the war ended. These women, called "Hello Girls," were civilians until 1978. They had to speak both French and English. They helped the French and British communicate. Over 300 women served in the Marines during World War I. They worked in the U.S. so male Marines could fight overseas. After the war in 1918, American women could no longer serve in the military, except as nurses, until 1942. However, in 1920, military nurses gained officer status.

19th Amendment: Women Get the Vote

Like most major nations, the United States gave women the right to vote at the end of World War I. The 19th Amendment to the Constitution, giving American white women the right to vote, passed in 1920. It came before the House of Representatives in 1918. Representative Frederick Hicks of New York left his dying wife's bedside at her urging to support the cause. He provided the final, crucial vote. However, the Senate did not pass the amendment that year. Congress approved the amendment the next year, on June 4, 1919. States began ratifying it. In 1920, Tennessee was the 36th state to do so. This met the requirement for it to become law. The remaining states ratified it later.

The amendment passed the Tennessee Senate easily. But in the House, there was strong opposition from the liquor industry. They thought women voters would pass Prohibition. The House ratified it by one vote. It officially became part of the Constitution on August 26, 1920. August 26 later became Women's Equality Day. Suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt calculated that the campaign involved 56 public votes, 480 campaigns to get legislatures to propose amendments, 47 campaigns for state constitutions, 277 campaigns for state party platforms, 30 campaigns for presidential party platforms, and 19 campaigns with 19 Congresses.

Black Women in the 1920s

Black women who moved to northern cities could vote starting in 1920. They played a new role in city politics. In Chicago, black women voters became a competition between middle-class women's clubs and black preachers. Important women activists in Chicago included Ida B. Wells and Ada S. McKinley. By 1930, black people made up over one-fifth of the Republican vote. They had a growing role in primary elections. For example, the Colored Women's Republican Club of Illinois showed its power in the 1928 primary. Their favorite, Ruth Hanna McCormick, won the nomination for U.S. Senate. White Republican leaders kept hoping for anti-lynching laws. Loyalty to Republicans as the "party of Lincoln" lasted until the New Deal Coalition offered more opportunities in the mid-1930s. There was also a class division. Middle-class black women reformers spoke of a hopeful future. But this did not connect with poor, uneducated maids and laundry workers. These women listened every Sunday to their preachers' promises of salvation.

Black Women in Business

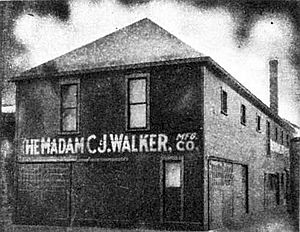

Most African-American business owners were men. However, women played a major role, especially in beauty. Beauty standards were different for white and black people. The black community developed its own standards, focusing on hair care. Beauticians could work from their homes. They did not need storefronts. So, black beauticians were many in the rural South, even without cities. They were pioneers in using cosmetics when rural white women in the South avoided them. As Blain Roberts showed, beauticians offered clients a place to feel pampered and beautiful within their community. Beauty contests started in the 1920s. In the white community, they were linked to agricultural fairs. In the black community, beauty contests grew from high school and college homecoming events. The most famous entrepreneur was Madame C.J. Walker (1867–1919). She built a national business called Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company based on her invention of the first successful hair straightening process.

Feminism in the 1920s

The first wave of feminism slowed down in the 1920s. After gaining voting rights, women's political activities generally decreased. Or they were absorbed into the main political parties. In the 1920s, they focused on issues like world peace and child welfare.

Gaining voting rights led feminists to focus on other goals. Groups like the National Women's Party (NWP) continued the political fight. Led by Alice Paul, the group proposed the Equal Rights Amendment in 1923. They worked to remove laws that discriminated against women based on sex. But many women shifted their focus from politics. They challenged traditional ideas of womanhood. Carrie Chapman Catt and others started The League of Women Voters. This helped women carry out their new responsibilities as voters.

The Roaring Twenties: New Women

A gap began to form between the "new" women of the 1920s and older women. Before the 19th Amendment, feminists thought women could not have both a successful career and a family. They believed one would stop the other. This idea began to change in the 1920s. More women wanted both successful careers and families. The "new" woman was less interested in social service than earlier generations. She was in tune with the money-making spirit of the era. She was eager to compete and find personal fulfillment.

The 1920s saw big changes for working women. World War I had temporarily allowed women into industries like chemical, automobile, and steel manufacturing. These were once thought unsuitable for women. Black women, who had been kept out of factory jobs, began to find a place in industry during World War I. They accepted lower wages and replaced immigrant workers. But like other women during World War I, their success was temporary. Most black women were pushed out of factory jobs after the war. In 1920, 75% of black female workers were farm laborers, domestic servants, and laundry workers. The booming economy of the 1920s meant more opportunities, even for lower classes. Many young girls from working-class backgrounds did not need to support their families as earlier generations did. They were often encouraged to find work or get job training. This could lead to social advancement.

The 1920s saw the rise of the co-ed. Women began attending large state colleges and universities. Women entered the mainstream middle-class experience. But they took on a gendered role in society. Women typically took classes like home economics, "Husband and Wife," "Motherhood," and "The Family as an Economic Unit." In a more traditional post-war era, it was common for a young woman to go to college to find a suitable husband.

The 1920s, a decade of free-market capitalism, gave birth to the "feminine mystique." This idea said that all women wanted to marry. All good women stayed home with their children, cooking and cleaning. The best women did all that and also used their buying power often to improve their families and homes.

Flappers: A New Style

The "new woman" was popular throughout the twenties. This meant a woman who rejected the old ways and often the politics of the older generation. She smoked and drank in public. She embraced consumer culture. Also called "flappers," these women wore short skirts (at first to the ankles, then to the knees). They had short, bobbed hair. Just as the flapper rejected long hair, she also threw away Victorian fashions, especially the corset. Corsets made women's curves stand out. Flappers preferred to be slender. This sometimes meant dieting or wearing tight undergarments to appear thin, flat-chested, and long-limbed. To look like a flapper and meet modern beauty standards, women also bought and used cosmetics. This was not common for respectable women before. These women pushed the boundaries of what was proper for a woman through their public activities.

Women's Firsts in the 1920s

Women achieved many groundbreaking firsts in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1921, Edith Wharton became the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. This was for her novel "The Age of Innocence." In 1925, Nellie Tayloe Ross became the first woman elected as a governor in the United States, for Wyoming. Also in 1925, the World Exposition of Women's Progress (the first women's world's fair) opened in Chicago. In 1926, Gertrude Ederle, born in New York, became the first woman to swim across the English Channel. She arrived almost two hours faster than any man before her. In 1928, women competed for the first time in Olympic field events. By 1928, women earned 39% of all college degrees in America. This was up from 19% at the start of the 1900s.

Italian American Women's Resistance

The American scene in the 1920s saw women's roles expand widely. This included the right to vote in 1920 and new standards for education and jobs. "Flappers" raised hemlines and lowered old restrictions in women's fashion. Italian-American media did not approve. It demanded that traditional gender roles be kept, where men controlled their families. Many traditional male-dominated values were strong among Southern European male immigrants. However, some practices like dowry were left behind in Europe. Community spokesmen were shocked by the idea of a woman with a secret ballot. They made fun of flappers and said feminism was wrong. They idealized an old male model of Italian womanhood. Mussolini was popular. When he expanded voting to include some women at the local level, Italian American writers agreed. They argued that the true Italian woman was, above all, a mother and a wife. Therefore, she would be a reliable voter on local matters. Feminist groups in Italy were ignored. Editors purposely linked women's freedom with Americanism. They turned the debate over women's rights into a defense of the Italian-American community's right to set its own rules.

The Great Depression: Challenges and Achievements

In 1932, Hattie Caraway of Arkansas became the first woman elected to the Senate. Also in 1932, Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic. She made her journey on the 5th anniversary of Lindbergh's solo Atlantic flight. President Herbert Hoover gave her the National Geographic Society's gold medal. Congress awarded her the Distinguished Flying Cross. Later in 1932, she became the first woman to fly solo nonstop coast to coast. She set the women's nonstop transcontinental speed record. In 1935, she became the first person to fly solo across the Pacific from Honolulu to Oakland, California. This was also the first flight where a civilian plane carried a two-way radio. Later in 1935, she became the first person to fly solo from Los Angeles to Mexico City. Still later in 1935, she became the first person to fly solo nonstop from Mexico City to Newark. In 1937, Amelia Earhart began a flight around the world but disappeared. Her remains, belongings, and plane have never been found. The first woman to fly solo around the world and return safely was American amateur pilot Jerrie Mock, who did so in 1964. In 1933, Frances Perkins was appointed by President Franklin Roosevelt as his Secretary of Labor. This made her the first woman to hold a job in a Presidential cabinet.

However, women also faced many challenges. A survey showed that between 1930 and 1931, 63% of cities fired female teachers as soon as they married. 77% did not hire married women as teachers. Also, a survey of 1,500 cities from 1930 to 1931 found that three-quarters of those cities did not hire married women for any jobs. In January 1932, Congress passed the Federal Economy Act. It said that no two people in the same family could work in government service at the same time. Three-fourths of employees fired because of this Act were women. However, during the Great Depression white women's unemployment rate was lower than men's. This was because women were paid less. Also, men would not take what they considered "women's jobs" like clerical work or domestic service. Yet, as unemployment rose, white women's move into professional and technical work slowed.

In 1939, black singer Marian Anderson sang on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. This was a major event in the civil rights movement. She had wanted to sing at Washington D.C.'s largest venue, Constitution Hall. But The Daughters of the American Revolution stopped her because of her race. Because of this, Eleanor Roosevelt, then the First Lady, resigned from the organization. This was one of the first actions by someone in the White House to address racial inequality. Anderson had performed at the White House three years earlier in 1936. This made her the first African-American performer to do so.

New Deal: Government Programs

Women received symbolic recognition under the New Deal (1933–43). But there was no effort to deal with their special needs. In relief programs, they could get jobs only if they were the main provider for their family. Still, relief agencies did find jobs for women. The WPA employed about 500,000 women. The largest number, 295,000, worked on sewing projects. They produced 300 million items of clothing and mattresses for people needing relief and for public places like orphanages. Many other women worked in school lunch programs.

Roosevelt appointed more women to office than any previous president. The first woman in his cabinet was Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins. His wife Eleanor played a very visible role supporting relief programs. In 1941, Eleanor became co-head of the Office of Civil Defense. She tried to involve women at the local level. But she argued with her co-head, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia, and had little impact on policy. Historian Alan Brinkley states that the New Deal did little more than symbolically address gender equality. New Deal programs mostly reflected traditional ideas about women's roles. They made few efforts toward women who wanted economic independence and professional opportunities.

Since 1941: Modern Women's History

World War II: Women in the Workforce

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, 12 million women were already working. This was one-quarter of the workforce. By the end of the war, the number was up to 18 million, one-third of the workforce. Eventually, 3 million women worked in war plants. But most women who worked during World War II were in traditionally female jobs, like the service sector. During this time, government messages encouraged women to join the workforce. The "Rosie the Riveter" image became popular. It showed women taking on male roles.

During the war, traditional gender roles changed somewhat. The "home" or domestic female sphere grew to include the "home front." Meanwhile, the public sphere, which was usually for men, became the international stage of military action.

Employment Changes

Wartime mobilization greatly changed how jobs were divided by gender for women. Young, able-bodied men were sent overseas. War manufacturing increased. During the war, an estimated 6.5 million women entered the workforce. Many women, including married ones, took various paid jobs. Many of these jobs were previously only for men. The biggest increase in female employment was in manufacturing. More than 2.5 million more women worked in manufacturing by 1944. This was a 140% increase. The "Rosie the Riveter" idea helped this happen.

The marital status of women who went to work changed a lot during the war. One in ten married women entered the workforce. They made up over 3 million of the new female workers. 2.89 million were single, and the rest were widowed or divorced. For the first time, there were more married women than single women in the female workforce. In 1944, 37% of all adult women were in the workforce. But nearly 50% of all women were actually employed at some point that year. The unemployment rate hit a historical low of 1.2%.

Women sought jobs for financial reasons. However, patriotic reasons also motivated many women. Women whose husbands were at war were more than twice as likely to seek jobs.

Women were thought to be doing "men's work." But the work women did was often suited to skills management thought women could handle. Management also advertised women's work as an extension of domesticity. For example, a company pamphlet said, "Note the similarity between squeezing orange juice and the operation of a small drill press." A Ford Motor Company publication said, "The ladies have shown they can operate drill presses as well as egg beaters." One manager said, "Why should men, who from childhood on never so much as sewed on buttons be expected to handle delicate instruments better than women who have plied embroidery needles, knitting needles and darning needs all their lives?" In these cases, women were hired for jobs management thought they could do based on their gender.

After the war, many women left their jobs voluntarily. One factory worker said, "I will gladly get back into the apron. I did not go into war work with the idea of working all my life. It was just to help out during the war." Other women were laid off to make room for returning veterans.

By the end of the war, many men who joined the service did not return. This left women to take sole responsibility for the household and provide for the family.

Black Women's Double V Campaign

Before the war, most black women were farm laborers in the South or domestic workers in Southern towns or Northern cities. Working with the Fair Employment Practices Committee, the NAACP, and unions, these black women fought a "Double V campaign." They fought against the Axis abroad and against unfair hiring practices at home. Their efforts changed the idea of citizenship. They linked their patriotism to war work. They sought equal job opportunities, government benefits, and better working conditions as rights for full citizens. In the South, black women worked in segregated jobs. In the West and most of the North, they were integrated. However, strikes happened in Detroit, Baltimore, and Evansville, Indiana. White migrants from the South refused to work alongside black women.

Nursing in Wartime

Nursing became a very respected job for young women. Most female civilian nurses volunteered for the Army Nurse Corps or the Navy Nurse Corps. These women automatically became officers. Teenaged girls joined the Cadet Nurse Corps. To help with the growing shortage at home, thousands of retired nurses volunteered in local hospitals.

Volunteer Activities

Women filled millions of jobs in community service roles. These included nursing, the USO, and the Red Cross. Unorganized women were encouraged to collect materials needed for the war effort. Women collected cooking fats. Children made balls of aluminum foil from gum wrappers and rubber band balls. These were given to the war effort. Hundreds of thousands of men joined civil defense units to prepare for disasters.

The Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP) mobilized 1,000 civilian women. They flew new warplanes from factories to airfields on the U.S. East Coast. This was important because flying warplanes had always been a male role. No American women flew warplanes in combat.

Baby Boom and Postwar Life

Marriage and motherhood became popular again as prosperity allowed couples who had delayed marriage to finally wed. The birth rate began to rise in 1941. It paused in 1944–45 as 12 million men were in uniform. Then it soared until the late 1950s. This was the "Baby Boom."

The federal government started the "EMIC" program. It provided free prenatal and birth care for the wives of servicemen below the rank of sergeant.

Housing shortages, especially in munitions centers, forced millions of couples to live with parents or in temporary housing. Little housing had been built during the Depression. So, shortages worsened until about 1949, when a massive housing boom finally met demand. (After 1944, much new housing was supported by the G.I. Bill.)

Federal law made it hard to divorce absent servicemen. So, divorces peaked when they returned in 1946. In the long run, divorce rates did not change much.

Housewives After the War

Women balanced their roles as mothers during the Baby Boom and the jobs they filled while men were at war. They struggled to complete all tasks. The war caused cuts in car and bus service. People moved from farms to munitions centers. Housewives who worked found their dual role difficult.

Stress came when sons, husbands, fathers, brothers, and fiancés were drafted. They were sent to training camps, preparing for a war where many would be killed. Millions of wives tried to move near their husbands' training camps.

At the end of the war, most munitions jobs ended. Many factories closed. Others changed to make civilian products. In some jobs, women were replaced by returning veterans. However, the number of women at work in 1946 was 87% of the number in 1944. This means 13% lost or quit their jobs. Many women working in machinery factories were taken out of the workforce. Many of these former factory workers found other jobs, like in kitchens or as teachers.

Women in Military Service

During World War II, 350,000 women served in the military. They were in the WACS, WAVES, SPARS, Marines, and as nurses. Over 60,000 Army nurses served in the U.S. and overseas. 67 Army nurses were captured by the Japanese in the Philippines in 1942. They were held as prisoners of war for over two and a half years. Over 14,000 Navy nurses served in the U.S., on hospital ships, and as flight nurses. Five Navy nurses were captured by the Japanese on Guam. They were held for five months. Another group of eleven Navy nurses were captured in the Philippines and held for 37 months.

Over 150,000 American women served in the Women's Army Corps (WAC) during World War II. The Corps was formed in 1942. Many Army WACs calculated bullet speed, measured bomb fragments, mixed gunpowder, and loaded shells. Others worked as draftswomen, mechanics, and electricians. Some trained in ordnance engineering. Later, women were trained to replace men as radio operators on U.S. Army hospital ships. This experiment worked. Female secretaries and clerks were soon assigned to hospital ships.

Eventually, the Air Force had 40% of all WACs in the Army. Women were weather observers, cryptographers, radio operators, sheet metal workers, and parachute riggers. They were also link trainer instructors, bombsight maintenance specialists, aerial photograph analysts, and control tower operators. Over 1,000 WACs ran statistical control machines. These were early computers used to track personnel records. By January 1945, only 50% of Air Force WACs held traditional jobs like file clerk or typist. A few Air Force WACs had flying duties. Three WACs received Air Medals. One was in India for mapping "the Hump," a mountainous air route. One woman died in a plane crash.

In 1942, the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) division was founded. It was an all-female part of the Navy. Over 80,000 women served in it. This included computer scientist Grace Hopper, who later became a rear admiral. While many WAVES had secretarial and clerical jobs, thousands performed unusual duties. These were in aviation, law, medicine, communications, intelligence, science, and technology. The WAVES ended, and women were accepted into the regular Navy in 1948.

SPARS (Semper Paratus Always Ready) was the United States Coast Guard Women's Reserve. It was created on November 23, 1942. Over 11,000 women served in SPARS during World War II. SPARs worked in the U.S. as storekeepers, clerks, photographers, and cooks. The program was mostly ended after the war.