History of Indiana facts for kids

Quick facts for kids History of Indiana |

|

|---|---|

The seal of Indiana reflects the state's pioneer era

|

|

| Historical Periods | |

| Pre-history | until 1670 |

| French Rule | 1679–1763 |

| British Rule | 1763–1783 |

| U.S. Territorial Period | 1783–1816 |

| Indiana Statehood | 1816–present |

| Major Events | |

| Tecumseh's War War of 1812 |

1811–1814 |

| Constitutional convention | June 1816 |

| Polly v. Lasselle | 1820 |

| Capitol moved to Indianapolis |

1825 |

| Passage of the Mammoth Internal Improvement Act |

1831 |

| State Bankruptcy | 1841 |

| 2nd Constitution | 1851 |

| Civil War | 1860–1865 |

| Gas Boom | 1887–1905 |

| Harrison elected president | 1888 |

| KKK scandal | 1925 |

The history of Indiana, a state in the Midwest, began with Native American tribes. They lived here as early as 8000 BC. Different tribes lived in the area for thousands of years. They reached their highest point of development during the Mississippian culture.

The first Europeans arrived in Indiana in the 1670s. They claimed the land for the Kingdom of France. France ruled for about 100 years, but few Europeans settled here. Great Britain defeated France in the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years' War). France then gave up its land east of the Mississippi River. Britain controlled the land for over twenty years. After losing the American Revolutionary War, Britain gave the entire region, including Indiana, to the new United States.

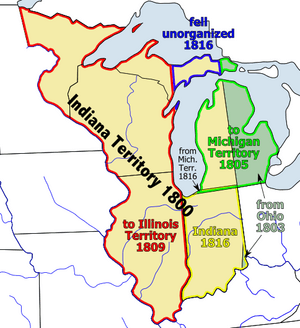

The U.S. government divided this large area into new territories. The biggest was the Northwest Territory. In 1800, Indiana Territory was created. As more people moved to Indiana Territory, it was divided in 1805 and again in 1809. It kept the name Indiana and became the 19th U.S. state in 1816.

The new state government wanted to turn Indiana from a frontier area into a busy, developed state. They started a plan to build roads, canals, railroads, and public schools. However, they spent too much money. By 1841, the state was almost bankrupt. It had to sell most of its public projects. In 1851, Indiana adopted a new Constitution. This led to big financial changes. Most public jobs were now chosen by election, not appointment. The power of the governor was also reduced. By 1860, Indiana had grown a lot and was the fourth-largest state by population.

Indiana became important in politics and played a big role for the Union during the American Civil War. Indiana was the first western state to get ready for the war. Its soldiers fought in almost every major battle. After the Civil War, Indiana remained politically important. It became a key state that often helped decide who would be president for about thirty years.

During the Indiana Gas Boom in the late 1800s, industries grew fast. The state's Golden Age of Literature also began then, making Indiana more culturally important. By the early 1900s, Indiana was a strong manufacturing state. Many immigrants and people from other parts of the U.S. moved here for jobs. The state faced challenges during the Great Depression in the 1930s. But building the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, growing the auto industry, and urban development helped its industries grow. In the second half of the 1900s, Indiana became a leader in the medicine industry. This was thanks to companies like Eli Lilly.

Contents

Early People of Indiana

After the last ice age, Indiana had many spruce and pine forests. Animals like mastodons, caribou, and saber-toothed cats lived here. Northern Indiana was covered by glaciers, but Southern Indiana was not. This allowed plants and animals to survive there, supporting early human groups.

First Inhabitants

The first known people in Indiana were Paleo-Indians. We have proof that humans were in Indiana as early as 8000–6000 BC. Camps of the traveling Clovis culture have been found. Carbon dating shows that people mined flint in Wyandotte Caves in Southern Indiana around 2000 BC. These early people ate many freshwater mussels from local streams. Their shell mounds are still found in southern Indiana.

The Early Woodland period in Indiana was from 1000 BC to 200 AD. During this time, the Adena culture grew. They learned to grow wild squash and make pottery. These were big steps forward from the Clovis culture. These native people built burial mounds. One of the oldest earthworks in Anderson's Mounds State Park is from this period.

Hopewell Culture

Native people in the Middle Woodland period developed the Hopewell culture. They might have been in Indiana as early as 200 BC. The Hopewells were the first culture to create lasting settlements in Indiana. Around 1 AD, they became skilled farmers, growing crops like sunflowers and squash. Around 200 AD, the Hopewells started building mounds for ceremonies and burials. Hopewell people in Indiana traded with other tribes as far away as Central America. For reasons we don't know, the Hopewell culture slowly disappeared around 400 AD and was gone by 500 AD.

The Late Woodland era began around 600 AD and lasted until Europeans arrived. This was a time of fast cultural change. One new thing that appeared was the use of stone for building. Large stone forts were built, many overlooking the Ohio River. These developments were likely influenced by the Mississippian culture.

Mississippian People

After the Hopewell culture ended, Indiana's population was low until the Fort Ancient and Mississippian cultures grew around 900 AD. The Ohio River Valley was home to many Mississippian people from about 1100 to 1450 AD. Like the Hopewell, they were known for their ceremonial earthwork mounds. Some of these are still visible near the Ohio River. The Mississippian mounds were much larger than the Hopewell mounds. The farming Mississippian culture was the first to grow maize (corn) in the region. They also developed the bow and arrow and learned copper working.

Mississippian society was complex and highly developed. Their largest city, Cahokia in Illinois, had up to 30,000 people. They had different social classes, with some groups specializing as artists. Leaders held both political and religious power. Their cities were usually built near rivers. They had a large central mound, smaller mounds, and an open plaza. Wooden walls were later built around their cities for defense. The remains of a major settlement called Angel Mounds are east of modern-day Evansville. Mississippian houses were usually square with plastered walls and thatched roofs. For unknown reasons, the Mississippians disappeared in the mid-1400s, about 200 years before Europeans came to Indiana. The Mississippian culture was the peak of native development in Indiana.

During this time, American Bison began to travel through Indiana. They crossed the Falls of the Ohio and the Wabash River near modern-day Vincennes. These herds were important to the people in southern Indiana. They created a well-used path called the Buffalo Trace, which European-American pioneers later used to move west.

Beaver Wars and European Arrival

Before 1600, a major war called the Beaver Wars broke out among Native Americans in eastern North America. Five Iroquois tribes joined together against their neighbors. They fought against a group of mostly Algonquian tribes. These included the Shawnee, Miami, Wea, Pottawatomie, and Illinois. These tribes were less advanced than the Mississippian culture that came before them. They were semi-nomadic, used stone tools, and did not build large structures or farms. The war lasted for at least a century. The Iroquois wanted to control the fur trade with Europeans. They drove other tribes south and west from the Ohio Valley.

As a result of the war, some tribes like the Shawnee moved into Indiana. They tried to settle on land belonging to the Miami. The Iroquois gained an advantage when Europeans supplied them with firearms. With these better weapons, the Iroquois took control of many tribes and nearly destroyed others in northern Indiana.

When the first Europeans came to Indiana in the 1670s, the Beaver Wars were ending. The French tried to trade firearms for furs with the Algonquian tribes in Indiana. This angered the Iroquois, who destroyed a French outpost. The French continued to supply the western tribes with weapons and allied with the Algonquian tribes. A major battle happened near modern South Bend. The Miami and their allies pushed back a large Iroquois force. With French firearms, the fight became more even. The war ended in 1701 with the Great Peace of Montreal. Both sides were tired from heavy losses. Much of Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana became less populated as tribes fled the fighting.

After the war, the Miami and Pottawatomie nations returned to Indiana. Other tribes, like the Algonquian Lenape, were pushed west from the East Coast by European settlers. Around 1770, the Miami invited the Lenape to settle on the White River. The Shawnee arrived in Indiana later. These four nations later fought in the Sixty Years' War. This was a struggle between native nations and European settlers for control of the Great Lakes region.

European Rule in Indiana

French fur traders from Canada were the first Europeans in Indiana, starting in the 1670s. The fastest way to connect the French areas of Canada and Louisiana was along Indiana's Wabash River. The Terre Haute area was seen as the border between these two French regions. This made Indiana a key part of French communication and trade routes. The French built Vincennes as a lasting settlement in Indiana, but most people in the area were still Native Americans. As French influence grew, Great Britain saw controlling Indiana as important to stop French expansion.

French Control (1679–1763)

The first European outpost in modern Indiana was Tassinong. It was a French trading post built in 1673 near the Kankakee River. French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle came to the area in 1679. He claimed it for King Louis XIV of France. La Salle explored a portage (a place to carry boats) between the St. Joseph and Kankakee rivers. In 1681, La Salle helped the Illinois and Miami nations agree to defend each other against the Iroquois.

More exploration led the French to create an important trade route between Canada and Louisiana. This route used the Maumee and Wabash rivers. The French built forts and outposts in Indiana. These were meant to stop the westward growth of the British colonies and to encourage trade with native tribes. The tribes traded animal furs for metal tools, cooking items, and other manufactured goods. The French built Fort Miamis in the Miami town of Kekionga (modern Fort Wayne, Indiana).

In 1717, Ouiatenon (modern Lafayette) was built to keep the Wea tribe from joining the British. In 1732, François-Marie Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes, built a similar post near the Piankeshaw tribe. This town is still named Vincennes. While other forts were temporary, Fort Vincennes was the only one to have a permanent European presence. Jesuit priests came with many French soldiers to try to convert native people to Christianity. They lived among the natives, learned their languages, and went with them on hunts. These missionaries became very influential and helped keep the native tribes allied with the French.

During the French and Indian War, the British fought France for control of the region. No big battles happened in Indiana, but the native tribes supported the French. They sent warriors to help the French fight the British. British forces captured key French outposts in Indiana, including Fort Miamis and Fort Vincennes. By 1761, the French were completely forced out of Indiana. After the French left, the native tribes, led by Chief Pontiac, tried to rebel against the British. They recaptured Fort Miamis and Fort Ouiatenon. In 1763, France signed the Treaty of Paris and gave control of Indiana to the British.

British Control (1763–1783)

When the British took control of Indiana, the region was in the middle of Pontiac's Rebellion. British officials negotiated with the tribes, breaking their alliance with Pontiac. Pontiac eventually lost most of his allies and made peace with the British in 1766. As a promise to Pontiac, Great Britain declared that the land west of the Appalachian Mountains would be for Native Americans. Despite this, Pontiac was still seen as a threat. After he was killed in 1769, the region had several years of peace.

After making peace with the natives, many French trading posts and forts were abandoned. Fort Miamis was kept for a few years but was also eventually abandoned. The Jesuit priests were sent away. No official government was set up, as the British hoped the French people in the area would leave. Many did, but the British slowly became more accepting of the French who stayed and continued the fur trade.

In 1768, a treaty was made between British colonies and the Iroquois. The Iroquois sold their land claims to the colonies. The company formed to hold this claim was called the Indiana Land Company. This was the first time the word Indiana was used. The colony of Virginia disagreed with this claim, as it already claimed the land through its royal charter. In 1773, Indiana was put under the control of the Province of Quebec. This was done to please its French population. The Quebec Act was one of the reasons the Thirteen Colonies gave for starting the American Revolutionary War. The colonies felt they deserved the land for helping Britain in the French and Indian War.

Even after the American Revolution, British influence on their Native American allies in the region remained strong, especially near Fort Detroit. This led to the Northwest Indian War. British-influenced native tribes refused to accept American rule, supported by British traders. American military victories and the Jay Treaty led to the British leaving their forts. However, the British were not fully gone until the end of the War of 1812.

United States Takes Control (1778–1800)

After the American Revolution began, George Rogers Clark was sent from Virginia. He was to claim much of the Great Lakes region for Virginia. In July 1778, Clark and about 175 men crossed the Ohio River. They took control of Kaskaskia, Vincennes, and other villages in British Indiana. They did this without fighting. Clark carried letters from the French ambassador saying that France supported the Americans. This made most French and Native American people in the area unwilling to support the British.

The fort at Vincennes, renamed Fort Sackville by the British, had been empty. Captain Leonard Helm became the first American commander there. To fight Clark, the British, led by Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton, took Vincennes back with a small force. In February 1779, Clark arrived at Vincennes in a surprise winter trip. He retook the town and captured Hamilton. This trip secured most of southern Indiana for the United States.

In 1780, French officer Augustin de La Balme formed a militia of French residents to capture Fort Detroit. On their way, they stopped to attack Kekionga. This delay was deadly. The expedition met Miami warriors led by Chief Little Turtle along the Eel River. The entire force was killed or captured. Clark planned another attack on Fort Detroit in 1781. But it was stopped when Chief Joseph Brant captured a large part of Clark's army. This happened at the battle known as Lochry's Defeat, near modern-day Aurora.

Other small fights happened in Indiana, including the battle at Petit Fort in 1780. In 1783, the war ended. Britain gave the entire region, including Indiana, to the United States in the peace treaty signed in Paris.

Clark's militia was under Virginia's authority. The area was governed as Virginia territory until the state gave it to the U.S. federal government in 1784. Clark received large areas of land in southern Indiana for his service. Modern Clark County is named after him.

Indiana Territory (1800–1816)

In 1785, the Northwest Indian War began. To end the native rebellion, the Miami town of Kekionga was attacked. Generals Josiah Harmar and Arthur St. Clair failed. St. Clair's Defeat was the worst defeat of the U.S. Army by Native Americans. This led to General "Mad Anthony" Wayne taking charge. He formed the Legion of the United States and defeated a Native American force at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. In 1795, the Treaty of Greenville was signed. A small part of eastern Indiana was opened for settlement. Fort Miami at Kekionga was taken by the United States and rebuilt as Fort Wayne. After the treaty, the powerful Miami nation considered themselves allies with the United States.

The Northwest Territory was created in 1787. It included all land between the Appalachian Mountains, the Mississippi River, the Great Lakes, and the Ohio River. This territory later became the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota. When it was created, there were only two American settlements in what would become Indiana: Vincennes and Clark's Grant. The European population was less than 5,000. The Native American population was estimated to be around 20,000, possibly as high as 75,000.

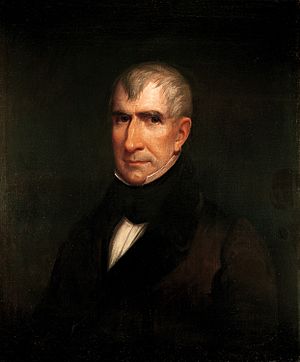

On July 4, 1800, the Indiana Territory was formed from the Northwest Territory. This was done to prepare for Ohio becoming a state. The name Indiana means "Land of the Indians." It referred to the fact that most of the area north of the Ohio River was still home to Native Americans. The first Governor of the Territory was William Henry Harrison. He served from 1800 to 1813. Harrison County was named after him. He later became the ninth President of the United States. Thomas Posey took over as governor from 1813 to 1816.

The first capital was Vincennes, where it stayed for thirteen years. After the territory was reorganized in 1809, plans were made to move the capital to Corydon. This was to be more central to the growing population. The new capitol building was finished in 1813. The government moved there quickly after war broke out on the frontier.

As the territory's population grew, people gained more freedoms. In 1809, the territory was allowed to elect its own legislature for the first time. Before that, Governor Harrison appointed the legislature. The Northwest Ordinance had forbidden slavery. However, it had existed in the region since French rule. Settlers from the Upper South brought slaves with them. They wanted slavery to be legal, but others from northern states opposed it. The anti-slavery group won a strong majority in the first election. Governor Harrison disagreed with the new legislature. They overturned the pro-slavery laws he had passed. Slavery remained a big issue in the state for decades. In these early years, the legislature did not encourage free black people to settle there, but it did allow them to vote.

War of 1812 in Indiana

The first major event in the territory was renewed fighting with Native Americans. Unhappy with how they had been treated since the peace of 1795, native tribes formed a group against the Americans. This group was led by the Shawnee Chief Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa. Tecumseh's War began in 1811. General William Henry Harrison led his army to stop Tecumseh's group. The war continued until the Battle of Tippecanoe. This battle ended the Native American uprising and gave Americans full control of Indiana. The battle made Harrison famous and earned him the nickname "Old Tippecanoe."

The war between Tecumseh and Harrison became part of the War of 1812. The remaining Native American forces allied with the British in Canada. The Siege of Fort Harrison is seen as the United States' first land victory in the war. Other battles in modern Indiana included the Siege of Fort Wayne, the Pigeon Roost Massacre, and the Battle of the Mississinewa. The Treaty of Ghent, signed in 1814, ended the war. It relieved American settlers from their fears of the British and their Native American allies. This marked the end of fighting with Native Americans in Indiana.

Indiana Becomes a State (1816)

In 1812, Jonathan Jennings became the territory's representative to Congress. Jennings immediately tried to make Indiana a state. However, the population was under 25,000, and the War of 1812 began, so no action was taken.

Governor Posey had caused problems by supporting slavery. Opponents like Jennings and Dennis Pennington wanted to use statehood to end slavery in the territory permanently.

Founding the State

In early 1816, the Territory took a census. The population was 63,897, which was enough for statehood. A special meeting to write the state's rules, called a constitutional convention, happened on June 10, 1816, in Corydon. Because it was so hot, the delegates often moved outside. They wrote the constitution under a giant elm tree. The state's first constitution was finished on June 29. Elections were held in August for the new state government. In November, Congress approved Indiana's statehood.

Jonathan Jennings and his supporters controlled the convention. Jennings was elected its president. Other important delegates included Dennis Pennington, Davis Floyd, and William Hendricks. Pennington and Jennings led the effort to ban slavery in Indiana. They succeeded, and a ban was put in the new constitution. However, people already held as slaves remained in that status for some time. While settlers did not want slavery, they also wanted to keep free black people from moving to the state. They created rules to limit their immigration.

Jonathan Jennings, whose motto was "No slavery in Indiana," was elected the first governor. He defeated Thomas Posey. Jennings served two terms as governor. Then he represented the state in Congress for 18 more years. After his election, Jennings declared Indiana a free state. The people who wanted to end slavery won an important victory in 1820. This was in the Indiana Supreme Court case of Polly v. Lasselle. Slavery was finally gone by 1830.

As Native American lands in the north opened up, Indiana's population grew quickly. The center of population kept moving north. Indianapolis was chosen as the new state capital in 1820 because it was in the middle of the state. The city's founders thought the White River would be a major transportation route. However, the river was too sandy for boats. In 1825, Indianapolis replaced Corydon as the seat of government. The government moved into the Marion County Courthouse, which was the second state capital building.

Early Growth and Challenges

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 2,632 | — | |

| 1810 | 24,520 | 831.6% | |

| 1820 | 147,178 | 500.2% | |

| 1830 | 343,031 | 133.1% | |

| 1840 | 685,866 | 99.9% | |

| 1850 | 988,416 | 44.1% | |

| 1860 | 1,350,428 | 36.6% | |

The National Road reached Indianapolis in 1829. This connected Indiana to the Eastern United States. Around this time, people from Indiana became known as Hoosiers. The state adopted the motto "Crossroads of America." In 1832, construction began on the Wabash and Erie Canal. This project connected the Great Lakes waterways to the Ohio River. However, railroads soon made canals less important. These transportation changes connected Indiana's economy more to the Northern East Coast. It no longer relied only on rivers that connected it to the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast states.

In 1831, work began on the third state capitol building. This building was designed by Ithiel Town and Alexander Jackson Davis. Its design was inspired by the Greek Parthenon. It opened in 1841. It was the first statehouse built and used only by the state government.

The state faced financial problems during its first thirty years. Jonathan Jennings tried to start a period of internal improvements. The Panic of 1819 caused the state's only two banks to fail. This hurt Indiana's credit and stopped projects. New projects didn't start until the 1830s. This was after the state's finances improved under governors William Hendricks and Noah Noble. Starting in 1831, big plans for statewide improvements began. Overspending on these projects led to a large debt. This debt was paid for by state bonds through the new Bank of Indiana and selling over nine million acres of public land. By 1841, the debt was too big to manage. The government had borrowed over $13 million, which was like fifteen years of tax money. It couldn't even pay the interest on the debt. The state barely avoided bankruptcy. It did this by giving its public projects to its creditors. In return, the state's debt was cut by 50%. The improvements started under Jennings paid off. The state began to grow rapidly, which slowly fixed its money problems. The improvements led to land values increasing four times. Farm produce increased even more.

During the 1840s, Indiana completed the removal of Native American tribes. Most of the Potawatomi moved to Kansas voluntarily in 1838. Those who didn't leave were forced to go to Kansas. This event is called the Potawatomi Trail of Death. Only the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians remained in Indiana. Most of the Miami tribe left in 1846. However, many members were allowed to stay on their private lands. This was under the terms of the 1818 Treaty of St. Mary's. Other tribes also agreed to leave the state voluntarily. They received money and land grants further west. The Shawnee moved to Missouri, and the Lenape moved to Canada. Other smaller tribes, like the Wea, moved west, mostly to Kansas.

By the 1850s, Indiana had changed a lot. What was once a frontier with few people became a developing state with several cities. In 1816, Indiana's population was about 65,000. In less than 50 years, it grew to over 1,000,000 people.

Because the state was changing so fast, the constitution of 1816 was criticized. People said it had too many appointed jobs. They also said some rules were too easily used by political parties that didn't exist when the constitution was written. The first constitution had not been voted on by the public. After the big population growth, it was seen as not good enough. A new constitutional convention was called in January 1851. The new constitution was approved on February 10, 1851. It was then voted on by the public that year. It was approved and has been the official constitution ever since.

Transportation Development

In the early 1800s, most goods in Indiana were moved by river. Most of the state's rivers flowed into the Wabash River or the Ohio River. These rivers eventually connected to the Mississippi River. Goods were then transported to and sold in St. Louis or New Orleans.

The first road in the region was the Buffalo Trace. This was an old bison trail that ran from the Falls of the Ohio to Vincennes. After the capital moved to Corydon, several local roads were built. These connected the new capital to the Ohio River at Mauckport and to New Albany. The first major road in the state was the National Road. This project was funded by the federal government. The road entered Indiana in 1829. It connected Richmond, Indianapolis, and Terre Haute with the eastern states. It eventually reached Illinois and Missouri in the west. The state used the advanced methods from the National Road to build a new statewide road network. This network could be used all year. The north–south Michigan Road was built in the 1830s. It connected Michigan and Kentucky and passed through Indianapolis. These two new roads crossed at roughly right angles and formed the base for Indiana's road system.

Indiana was flat and had many rivers. This led to heavy spending on canals in the 1830s. Planning began in 1827 after New York had great success with its Erie Canal. In 1836, the legislature set aside $10 million for a large network of internal improvements. This included canals, turnpikes, and railroads. The goal was to encourage settlement by providing easy, cheap access to all parts of the state. It aimed to connect every area to the Great Lakes and Ohio River. From there, goods could reach Atlantic seaports and New Orleans. Everyone was very excited, but the plan was a financial disaster. The legislature required that work start on all parts of all projects at the same time. Very few were finished. The state could not pay the bonds it issued. It was then blacklisted by financial groups in the East and Europe for decades.

The first major railroad line was finished in 1847. It connected Madison with Indianapolis. By the 1850s, railroads became popular in Indiana. Indianapolis was a central point. Indiana had 212 miles of railroad in 1852. This jumped to 1,278 miles in 1854. These were run by 18 companies. Plans were underway to double these numbers. The successful railroad network brought big changes to Indiana. It also boosted the state's economic growth. Indiana's natural waterways connected it to the South through cities like St. Louis and New Orleans. However, the new rail lines ran east–west. They connected Indiana with the economies of the northern states. By mid-1859, no rail line yet crossed the Ohio or Mississippi rivers. Because of increased demand and the embargo against the Confederacy, the rail system was mostly finished by 1865.

Civil War in Indiana (1861–1865)

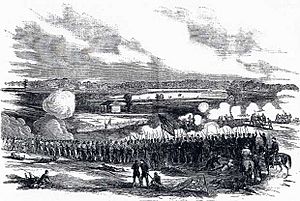

Indiana, a free state and the boyhood home of Abraham Lincoln, stayed with the Union during the American Civil War. Indiana regiments fought in all the major battles of the war. They were in almost all the battles in the western part of the country. Hoosiers were present in the first and last battles of the war. During the war, Indiana provided 126 infantry regiments, 26 artillery batteries, and 13 cavalry regiments to the Union cause.

In 1861, Indiana was asked to provide 7,500 men for the Union Army. So many volunteered that thousands had to be turned away. Before the war ended, Indiana sent 208,367 men to fight and serve. Over 35% of these men became casualties. 24,416 died, and over 50,000 more were wounded.

When the war started, Indiana's state legislature had a Democratic majority. Many of them sympathized with the South. Governor Oliver Morton illegally borrowed millions of dollars to pay for the army. This allowed Indiana to contribute so much to the war effort. Morton stopped the state legislature from meeting in 1861 and 1862. He did this with the help of the Republican minority. This prevented Democrats from interfering with the war effort or trying to leave the Union.

Supporting the Troops

In March 1862, Governor Oliver Morton also created the Indiana Sanitary Commission. This committee raised money and gathered supplies for soldiers. In January 1863, the commission started recruiting women as nurses for wounded soldiers. Notable women members included Mary F. Thomas, a Hoosier suffragist, and Eliza Hamilton-George, known as "Mother George." The exact number of women volunteers is unknown. However, William Hannaman, president of the Indiana Sanitary Commission, reported in 1866 that "about two hundred and fifty" women volunteered as nurses between 1863 and 1865.

Raids in Indiana

Two raids on Indiana soil during the war caused brief panic. The Newburgh Raid happened on July 18, 1862. Confederate officer Adam Johnson briefly captured Newburgh. He tricked Union troops into thinking he had cannons on the hills. In reality, they were just camouflaged stovepipes. This raid convinced the federal government to send a permanent force of regular Union Army soldiers to Indiana. This was to stop future raids.

The most important Civil War battle in Indiana was a small fight during Morgan's Raid. On July 9, 1863, Morgan tried to cross the Ohio River into Indiana. He had 2,400 Confederate cavalry. After a brief fight, he marched north to Corydon. There, he fought the Indiana Legion in the short Battle of Corydon. Morgan took control of the hills south of Corydon. He fired two shells into the town, which quickly surrendered. The battle resulted in 15 deaths and 40 wounded. Morgan's main group of troopers briefly raided New Salisbury, Crandall, Palmyra, and Salem. Fear spread in the capital. The militia began to gather to stop Morgan. However, after Salem, Morgan turned east. He raided and fought along his path. He left Indiana through West Harrison on July 13 and went into Ohio, where he was captured.

After the War

The Civil War greatly affected Indiana's development. Before the war, most people lived in the south of the state. Many had come through the Ohio River. This river provided a cheap way to export products and farm goods to New Orleans. The war closed the Mississippi River for almost four years. This forced Indiana to find other ways to export its goods. This led to people moving north. The state began to rely more on the Great Lakes and the railroad for exports.

Before the war, New Albany was the largest city in the state. This was mainly because of its river connections and trade with the South. Over half of Hoosiers with over $100,000 lived in New Albany. During the war, trade with the South stopped. Many people thought New Albany residents were too friendly to the South. The city never regained its former importance. It remained a city of 40,000 people. Its early-Victorian Mansion-Row buildings still stand from its boom period.

Indiana After the Civil War

Economic Growth and Industry

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 1,680,637 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,978,301 | 17.7% | |

| 1890 | 2,192,404 | 10.8% | |

| 1900 | 2,516,462 | 14.8% | |

| 1910 | 2,700,876 | 7.3% | |

| 1920 | 2,930,390 | 8.5% | |

| 1930 | 3,238,503 | 10.5% | |

Ohio River ports had been hurt by the trade ban with the Confederate South. They never fully recovered, leading to an economic decline in southern Indiana. In contrast, northern Indiana experienced a big economic boost. Natural gas was discovered there in the 1880s. This led to the rapid growth of cities like Gas City, Hartford City, and Muncie. A glass industry developed there to use the cheap fuel. The Indiana gas field was the largest known in the world at that time. This boom lasted until the early 1900s when gas supplies ran low. This marked the beginning of northern Indiana's industrialization.

The growth of heavy industry attracted thousands of European immigrants in the late 1800s and early 1900s. It also brought people from rural and small towns in the South, both black and white. These changes greatly altered the state's population. Indiana's industrial cities were among the destinations for the Great Migration of African Americans. After World War II, changes in industry led to Indiana becoming part of the Rust Belt.

In 1876, chemist Eli Lilly, a Union colonel during the Civil War, founded Eli Lilly and Company. This was a pharmaceutical (medicine) company. His first invention, gelatin-coating for pills, led to rapid growth. The company eventually became Indiana's largest corporation and one of the largest in the world. Over the years, the company developed many widely used drugs, including insulin. It was also the first company to mass-produce penicillin. The company's many advances made Indiana a leading state in producing and developing medicines.

Charles Conn returned to Elkhart after the Civil War. He started C.G. Conn Ltd., a company that made musical instruments. The company's new ideas in band instruments made Elkhart an important center for music. It became a key part of Elkhart's economy for decades. Nearby South Bend continued to grow after the Civil War. It became a large manufacturing city focused on the Oliver Farm Equipment Company, which was the nation's leading plow maker. Gary was founded in 1906 by the United States Steel Corporation as the location for its new factory.

Governor James D. Williams's administration suggested building the fourth state capitol building in 1878. The third state capitol building was torn down, and the new one was built on the same spot. Two million dollars were set aside for construction. The new building was finished in 1888. This building was still in use in 2008.

The Panic of 1893 had a very negative effect on Indiana's economy. Many factories closed, and several railroads went bankrupt. The Pullman Strike of 1894 hurt the Chicago area. Coal miners in southern Indiana joined a national strike. Hard times were not only for industry; farmers also felt a financial squeeze from falling prices. The economy began to recover when World War I started in Europe. This created a higher demand for American goods. Despite economic problems, advances in industrial technology continued through the late 1800s and into the 1900s. On July 4, 1894, Elwood Haynes successfully tested his first automobile. He opened the Haynes-Apperson auto company in 1896. In 1895, William Johnson invented a process for casting aluminum.

Indiana's Political Role

After the Civil War, Indiana became a key "swing state." This meant it often helped decide which political party would control the presidency. Elections were very close. They became the focus of intense attention, with many parades, speeches, and rallies before election day. Voter turnout was very high, often over 90% in elections like 1888 and 1896. In some areas, both sides paid their supporters to vote, and sometimes paid opponents not to vote. Despite claims, historians have found very little fraud in national elections.

To win the electoral vote, both national parties looked for Indiana candidates for their presidential tickets. A Hoosier was included in almost every presidential election between 1880 and 1924.

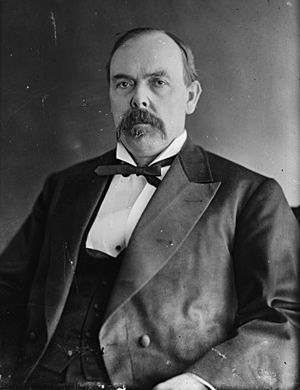

In 1888, Indiana Senator Benjamin Harrison, grandson of territorial Governor William Henry Harrison, was elected President. This happened after a strong campaign that brought over 300,000 people to Indianapolis to hear him speak from his famous front porch. Fort Benjamin Harrison was named in his honor. Five Hoosiers have been elected as Vice-President. The most recent was Dan Quayle, elected in 1988.

Cultural Flourishing

The late 1800s began what is known as the "golden age of Indiana literature." This period lasted until the 1920s. Edward Eggleston wrote The Hoosier Schoolmaster (1871), the first best-selling book from the state. Many others followed, including Maurice Thompson's Hoosier Mosaics (1875) and Lew Wallace's Ben-Hur (1880). Indiana gained a reputation as the "American heartland" after several popular novels. These included Booth Tarkington's The Gentleman from Indiana (1899), Meredith Nicholson's The Hoosiers (1900), and Thompson's second famous novel, Alice of Old Vincennes (1900). James Whitcomb Riley, known as the "Hoosier Poet," wrote hundreds of poems celebrating Indiana themes, including Little Orphant Annie.

A unique art culture also began in the late 1800s. This started the Hoosier Group of landscape painting and the Richmond Group of impressionist painters. These painters were known for their use of bright colors. Artists like T. C. Steele were influenced by the colorful hills of southern Indiana. Important musicians and composers from Indiana also became nationally famous. These included Paul Dresser, whose most popular song, "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away", later became the official state song.

Women's Rights and Social Change

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, prohibition (banning alcohol) and women's suffrage (the right to vote) became major reform issues. While many Protestant churches in Indiana supported temperance, few openly discussed women's voting rights.

The push for women's suffrage became strong again in the 1870s. It was supported by leaders of the prohibition movement, especially the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). The Indiana branch of the American Woman Suffrage Association was re-established in 1869. In 1878, May Wright Sewall founded the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society. This group also worked for world peace before World War I. Several Indiana women also became temperance leaders. The Indiana chapter of the WCTU was formed in 1874 with Zerelda G. Wallace as its first president. Like many suffrage leaders, Wallace became a strong supporter of women's suffrage through her temperance work. During her 1875 speech to the Indiana General Assembly supporting prohibition, lawmakers showed disrespect for women involved in politics. Afterward, Wallace said this experience made her embrace suffrage.

The first major effort to give women the right to vote in all non-federal elections tried to change the state constitution. It passed both houses of the state legislature in 1881. However, the bill failed to pass in the next legislative session in 1883, as state law required. Temperance efforts didn't fare much better. In 1881, the Indiana chapter of the WCTU and other groups successfully pushed the Indiana General Assembly to pass an amendment to ban alcohol. But the Indiana Liquor League and a Democratic majority in the legislature stopped the bill in 1883. After these defeats, women's suffrage and prohibition became sensitive issues in local politics.

To gain political power for prohibition laws, a state Prohibition Party was formed in 1884. However, it never gathered many voters. Many temperance supporters continued to work within the more established political parties. The issue of alcohol divided people into "wets" (who supported alcohol) and "drys" (who opposed it). This became a main theme in Indiana politics until the 1930s. One success happened in 1895. The state legislature passed the Nicholson law. This law allowed voters in a city or township to file a remonstrance. This would prevent an individual saloon owner from getting a liquor license. The Anti-Saloon League became a powerful political force. It encouraged Protestant voters to support dry laws. One leading supporter of the temperance movement in Indiana was Emma Barrett Molloy. She was an active member of the WCTU and spoke across the country to promote banning alcohol. Through her activism, Molloy also became a strong supporter of women's rights, especially freedom of speech.

In May 1906, a meeting was held in Kokomo to restart the Indiana suffragist movement. An Indiana Auxiliary of the National American Woman Suffrage Association was formed, and officers were elected.

In 1911, a suffrage group was formed when the Indianapolis Franchise Society and the Legislation Council of Indiana Women merged. They formed the Women's Franchise League of Indiana (WFL). The WFL was part of the national suffrage organization. The league helped women get the right to vote at the state level. It had 1,205 members in thirteen districts. After the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted, the Women's Franchise League of Indiana became the League of Indiana Women Voters.

White middle-class women in Indiana learned how to organize through the suffrage and temperance movements. By the 1890s, they used these skills to help their communities. They formed women's clubs that combined reading with social work. They focused on public health, sanitation, and good schools. Hoosier women worked at both state and local levels to bring about Progressive Era reforms. For example, in Lafayette, suffragists focused on the Lafayette Franchise League. Those interested in social issues worked through the Lafayette Charity Organization Society (LCOS) and other groups. Albion Fellows Bacon led statewide and national efforts for housing reform. She worked to pass housing laws in Indiana in 1909, 1913, and 1917. Women in Indiana officially gained the right to vote in 1920 when the 19th Amendment was ratified for the United States Constitution.

Middle-class black women activists organized through African American Baptist and Methodist churches. Under the leadership of Hallie Quinn Brown, they formed a statewide group called the Indiana Association of Colored Women's Clubs. Racism prevented this group from joining its white counterpart. White Hoosier suffragist May Wright Sewall spoke at the founding convention to show support for Black Hoosier women. The Indiana Association of Colored Women's Clubs sponsored 56 clubs in 46 cities. By 1933, it had 2,000 members and a budget of over $20,000. Most members were public school teachers or hairdressers. They were also women active in local black businesses and government. One of the most famous members in Indiana was Madame C. J. Walker of Indianapolis. She owned a nationally successful business selling beauty and hair products for black women. Club meetings focused on home-making classes, research on the status of African Americans, suffrage, and anti-lynching activism. Local clubs ran rescue missions, nursery schools, and educational programs.

Twentieth Century Indiana

Economic Changes

Even though industry was growing fast in northern Indiana, the state was still mostly rural in the early 1900s. It had a population of 2.5 million. Like much of the Midwest, Indiana's main exports and jobs were in agriculture until after World War I. Indiana's growing industry, supported by cheap natural gas, an educated population, low taxes, easy transportation, and business-friendly government, helped it become a leading manufacturing state by the mid-1920s.

The state's central location gave it a dense network of railroads. The Monon Line was especially identified with Indiana. It provided passenger service for students going to Purdue, Indiana University, and many small colleges. It painted its cars in school colors and was very popular on football weekends. The Monon merged into larger lines in 1971, stopped passenger service, and lost its identity. Business people built a large "interurban" network of light rails. These connected rural areas to shopping in cities. They started in 1892. By 1908, there were 2,300 miles of track in 62 counties. The automobile made these lines unprofitable unless the destination was Chicago. By 2001, the "South Shore" was the last one still running from South Bend to Chicago.

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway complex was built in 1909. This started a new era in history. Most Indiana cities within 200 miles of Detroit became part of the huge automobile industry after 1910. The Indianapolis speedway was a place for auto companies to show off their products. The Indianapolis 500 quickly became the top auto race. European and American companies competed to build the fastest car and win at the track. Industrial and technological industries thrived during this time. George Kingston developed an early carburetor in 1902. In 1912, Elwood Haynes received a patent for stainless steel.

Statewide Prohibition

In the first two decades of the 1900s, the Indiana Anti-Saloon League (IASL) and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union successfully pressured Indiana politicians. They especially targeted members of the Republican party to support the cause of banning alcohol. The IASL became a key force behind efforts to pass statewide prohibition in early 1917. It also gathered state support for the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919. The IASL's success, led by Edward S. Shumaker, a Methodist minister, made it a model for other state organizations. Shumaker told politicians he didn't care if they drank. But he insisted they vote for dry laws or face defeat in the next election by dry voters.

In 1905, the Moore amendment expanded the state's Nicholson local option law. It applied to all liquor license applicants within a local township or city ward. The next step was to seek countywide prohibition. The IASL appealed to the public, holding large rallies to support a county option law. This would create a stricter ban on alcohol. In September 1908, Indiana governor J. Frank Hanly, a Methodist, Republican, and teetotaler, called for a special legislative session. He wanted to establish a county option that would let county voters ban alcohol sales throughout their county. The state legislature passed the bill by a narrow margin. By November 1909, seventy of Indiana's ninety-two counties were dry. In 1911, a Democratic legislature replaced the county option with the Proctor law, a less strict local option. The number of dry counties dropped to twenty-six. Despite this setback, prohibition supporters continued to lobby lawmakers. In December 1917, several temperance groups formed the Indiana Dry Federation. They fought against the powerful liquor industry. The IASL joined the group shortly after. The Federation and the League strongly campaigned for statewide prohibition. The Indiana General Assembly adopted it in February 1917. Legal challenges delayed its start until 1918. A court ruled in June that Indiana's prohibition law was constitutional.

On January 14, 1919, Indiana became the twenty-fifth state to ratify the Eighteenth Amendment. This amendment required nationwide prohibition. Three days later, Nebraska became the thirty-sixth state to ratify it, providing the two-thirds majority needed. Nationwide Prohibition began on January 17, 1920. Efforts then focused on enforcing the new law. Protestant support for Prohibition remained strong in Indiana in the 1920s. Shumaker and the IASL led a statewide campaign that successfully passed a new prohibition law for the state. This was the Wright bone-dry law, enacted in 1925. The Wright law was part of a national trend toward stricter prohibition laws. It imposed severe penalties for alcohol possession.

The Great Depression and the election of Democratic candidates in 1932 ended widespread national support for Prohibition. Franklin D. Roosevelt promised to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment in his 1932 presidential campaign. He kept his promise. On December 5, 1933, the Twenty-first Amendment repealed the Eighteenth Amendment. This ended nationwide Prohibition. However, Indiana's legislature continued to regulate alcohol within the state. It did this through state liquor licenses and banning sales on Sunday.

Floods and World War I

Between March 23 and March 27, 1913, Indiana and many other states experienced major flooding during the Great Flood of 1913. It was Indiana's worst flood disaster at that time. The weather system that caused the flood arrived in Indiana on Sunday, March 23, with a major tornado at Terre Haute. In four days, over nine inches of rain fell in southern Indiana. More than half of it fell in just twenty-four hours on March 25. Heavy rains, runoff, and rising rivers caused widespread flooding in northeast, central, and southern Indiana. Indiana's flood-related deaths were estimated at 100 to 200. Flood damage was estimated at $25 million (in 1913 dollars). State and local communities handled their own disaster response and relief. The American Red Cross, a small organization then, set up a temporary headquarters in Indianapolis. It served the six hardest-hit Indiana counties. Indiana governor Samuel M. Ralston asked Indiana cities and other states for help. He appointed a trustee to receive relief funds and arrange for distributing supplies. Independent organizations, like the Rotary Club of Indianapolis, also helped with local relief efforts.

Hoosiers were divided about entering World War I. Before Germany started unrestricted submarine warfare and tried to get Mexico as an ally in 1917, most Hoosiers wanted the U.S. to stay neutral. Support for Britain came from professionals and businessmen. Opposition came from church leaders, women, farmers, and Irish Catholics and German-American groups. They called for neutrality and strongly opposed going to war to help the British Empire. Important Hoosiers who opposed the war included Democratic Senator John W. Kern and Vice President Thomas R. Marshall. Supporters of military readiness included James Whitcomb Riley and George Ade. Most of the opposition disappeared when the United States officially declared war against Germany in April 1917. However, some teachers lost their jobs due to suspicion of disloyalty, and public schools could no longer teach in German. Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs, from Terre Haute, went to federal prison for encouraging young men to avoid the draft.

The Indiana National Guard was federalized during WWI. Many units were sent to Europe. A separate group, the Liberty Guard, had been formed in 1910, mainly for social purposes. Members marched in parades and patriotic events. Governor Samuel Ralston had to call out the Liberty Guard in November 1913 to stop a growing workers strike in Indianapolis. By 1920, the state decided to make this group official. It was renamed the Indiana Civil Defense Force and given equipment and training. In 1941, the unit was named the Indiana Guard Reserve. It became a state militia. During World War II, it was again federalized, and members were called up by the federal government.

Indiana provided 130,670 troops during the war. Most of them were drafted. Over 3,000 men died, many from influenza and pneumonia. To honor the Hoosier veterans of the war, the state began building the Indiana World War Memorial. It was not finished until 1965.

The 1920s and the Great Depression

The war-time economy boosted Indiana's industry and agriculture. This led to more people moving to cities throughout the 1920s. By 1925, more workers in Indiana were employed in industry than in agriculture. Indiana's biggest industries were steel production, iron, automobiles, and railroad cars.

A scandal broke out across the state in 1925. It was discovered that over half the seats in the General Assembly were controlled by the Indiana Ku Klux Klan. This included members from three political parties. The Klan pushed for anti-Catholic laws, including a ban on parochial (religious) education. During the 1925 General Assembly session, Grand Dragon D. C. Stephenson famously boasted, "I am the law in Indiana." Stephenson was convicted of murder that year and sentenced to life in prison. Governor Edward L. Jackson, whom Stephenson helped elect, refused to pardon him. Stephenson then started naming many of his co-conspirators. This led to a string of arrests and charges against political leaders. These included the governor, the mayor of Indianapolis, the attorney general, and many others. This crackdown effectively made the Klan powerless.

During the 1930s, Indiana, like the rest of the nation, was affected by the Great Depression. This economic downturn had a wide-ranging negative impact on Indiana. Urbanization (people moving to cities) declined. Governor Paul V. McNutt's administration struggled to build a state-funded welfare system from scratch. This was to help the overwhelmed private charities. During his time as governor, spending and taxes were cut drastically because of the Depression. The state government was completely reorganized. McNutt also enacted the state's first income tax. On several occasions, he declared martial law (military rule) to end worker strikes.

During the Great Depression, unemployment was over 25% statewide. Southern Indiana was hit hard, with unemployment topping 50% during the worst years. The federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) began operations in Indiana in July 1935. By October of that year, the agency had put 74,708 Hoosiers to work. In 1940, there were still 64,700 people working for the agency. Most of these workers improved the state's infrastructure. This included roads, bridges, flood control projects, and water treatment plants. Some helped organize library collections. Artists were hired to create murals for post offices and libraries. Nearly every community had a project to work on.

During the 1930s, many local businesses collapsed. Several railroads went bankrupt, and many small rural banks failed. Manufacturing stopped or was greatly reduced because demand for products dropped. The Depression continued to negatively affect Indiana until the buildup for World War II. Its effects were felt for many years afterward.

World War II in Indiana

The economy started to recover in 1933. However, unemployment remained high among young and older workers until 1940. This was when the federal government began building up supplies and weapons for World War II.

Indiana played a part in the nation's economic and resource mobilization. Within the state, munitions were produced at an army plant near Sellersburg. The P-47 fighter-plane was made in Evansville at Republic Aviation. The steel produced in northern Indiana was used in tanks, battleships, and submarines. Other war-related materials were produced throughout the state. Indiana's military bases were activated. Areas like Camp Atterbury saw their highest activity levels ever.

The population strongly supported the war efforts. The political left supported the war, unlike World War I, which Socialists opposed. Churches showed much less pacifism than in 1914. The Church of God, based in Anderson, had a strong pacifist element. This reached its peak in the late 1930s. However, the Church saw World War II as a just war because America was attacked. Anti-Communist feelings have since kept strong pacifism from developing in the Church of God. Similarly, the Quakers, with a strong base near Richmond, generally saw World War II as a just war. About 90% served, though there were some who refused to fight for moral reasons. The Mennonites and Brethren continued their pacifism, but the federal government was much less hostile than before. The churches helped their young men become conscientious objectors and provide valuable service to the nation. Goshen College set up a training program for unpaid Civilian Public Service jobs. Young women pacifists were not subject to the draft. However, they volunteered for unpaid Civilian Public Service jobs to show their patriotism. Many worked in mental hospitals.

The state sent nearly 400,000 Hoosiers who enlisted or were drafted. More than 11,783 Hoosiers died in the conflict, and another 17,000 were wounded. Hoosiers served in all the major war zones. Their sacrifice was honored by additions to the World War Memorial in Indianapolis, which was not finished until 1965.

Tens of thousands of women volunteered for war service through groups like the Red Cross. One example was Elizabeth Richardson of Mishawaka. She served coffee and doughnuts to soldiers in England and France from a Red Cross clubmobile. She died in a plane crash in 1945 in France.

Indiana in the 21st Century

Central Indiana was hit by a major flood in 2008. This caused widespread damage and forced hundreds of thousands of residents to leave their homes. It was the most costly disaster in the state's history, with early damage estimates over $1 billion.

In 2012, Indiana's exports totaled US$34.4 billion. This was a record high for the state. The rate of export growth in 2012 was faster in Indiana than it was for the entire nation.

Higher Education in Indiana

For a list of institutions, see Category:Universities and colleges in Indiana. The earliest places for education in Indiana were missions. These were set up by French Jesuit priests to convert local Native American nations. The Jefferson Academy was founded in 1801 as a public university for the Indiana Territory. It was reincorporated as Vincennes University in 1806, becoming the first university in the state.

The 1816 constitution required Indiana's state legislature to create a "general system of education." This system would go from township schools to a state university. Tuition would be free and open to everyone. It took several years for the legislature to keep this promise. This was partly due to a debate about whether a new public university should replace the territorial university. The 1820s saw the start of free public township schools. During Governor William Hendricks's time, a piece of land was set aside in each township to build a schoolhouse.

The state government officially started Indiana University in Bloomington in 1820. It was called the State Seminary. Construction began in 1822. The first professor was hired in 1823, and classes started in 1824.

Other state colleges were established for specific needs. These included Indiana State University, founded in Terre Haute in 1865. It was the state normal school for training teachers. Purdue University was founded in 1869 as the state's land-grant university. It focused on science and agriculture. Ball State University was founded as a normal school in the early 1900s and given to the state in 1918.

Public colleges were behind private religious colleges in size and education standards until the 1890s. In 1855, North Western Christian University (now Butler University) was started by Ovid Butler. This happened after a split with the Christian Church Disciples of Christ over slavery. Importantly, the university was founded on the basis of being anti-slavery and allowing both boys and girls to study together (co-education). It was one of the first to admit African Americans. It was also one of the first to have a named position for female professors, the Demia Butler Chair in English. Asbury College (now DePauw University) was Methodist. Wabash College was Presbyterian. These led the Protestant schools. The University of Notre Dame, founded by Rev Edward Sorin in 1842, is a well-known Catholic college. Indiana lagged behind the rest of the Midwest with lower literacy and education rates into the early 1900s.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Indiana para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Indiana para niños