Technological and industrial history of the United States facts for kids

The technological and industrial history of the United States tells the story of how the U.S. became one of the most advanced nations in the world. Many things helped this happen quickly: lots of land, skilled workers, a focus on new businesses, different climates, and big markets where people wanted to buy things. It also helped that there was plenty of money, good rivers for transport, and lots of natural resources for energy.

Fast transportation, like the huge railroad system built in the mid-1800s and the Interstate Highway System in the late 1900s, made markets bigger and lowered shipping costs. The laws also made it easy to start businesses and ensured agreements were kept. When the U.S. was cut off from Europe during the War of 1812, American business owners started factories in the Northeast, using new ideas from Britain.

Since it became an independent country, the United States has always encouraged science and new ideas. Because of this, the U.S. has been the birthplace of many important inventions. These include the airplane, the internet, the microchip, the laser, cellphones, refrigerators, email, microwaves, personal computers, liquid-crystal display and light-emitting diode technology, air conditioning, the assembly line, the supermarket, the bar code, and the automated teller machine.

The early growth of technology and industry in the U.S. happened because of a special mix of geography, society, and money. There weren't enough workers, so wages were higher than in Britain and Europe. This encouraged people to invent machines to do tasks. Americans also had advantages like being former British subjects, having good English reading skills (over 80% in New England), and strong British laws and courts that protected property rights. They had a good foundation to build on. Unlike Britain, the U.S. didn't have old aristocratic systems that could slow things down.

The eastern coast had many rivers and streams, perfect for building textile mills needed for early industrialization. Samuel Slater, who had worked in British textile mills, came to New England in 1789 and helped set up the first successful textile industry. A lot of natural resources, the know-how to build and power machines, and a workforce of mobile workers (often young, unmarried women) all helped early industrialization. European immigrants also brought knowledge from the European Industrial and Scientific Revolutions, which helped in creating new businesses and technologies. A government that allowed businesses to succeed or fail on their own also played a part.

After the American Revolution ended in 1783, the new government continued to protect property rights and set up laws to ensure this. The idea of patents was even put into the U.S. Constitution. This allowed Congress to give inventors the exclusive right to their discoveries for a limited time, encouraging new ideas. The invention of the Cotton gin by Eli Whitney made cotton a cheap and easy-to-get resource for the new textile industry.

A big push for the U.S. to enter the Industrial Revolution came from the Embargo Act of 1807, the War of 1812, and the Napoleonic Wars. These events cut off supplies of cheaper goods from Britain. Not being able to buy these goods strongly encouraged Americans to develop their own industries and make their own products instead of just buying from Britain.

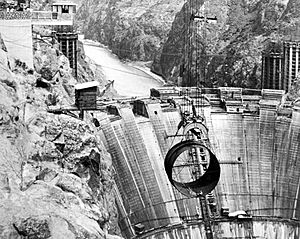

Experts say that the greatest economic and technological progress in the U.S. happened between the late 1800s and the mid-1900s. During this time, the country changed from being mostly about farming to becoming the world's leading industrial power, producing more than a third of all industrial goods globally.

The American colonies gained independence in 1783, just as factories were starting to replace artisans. The growth of transportation and new inventions before the American Civil War helped industries grow and become more organized. By the early 1900s, American industry was stronger than Europe's, and the U.S. started to show its military power. Even though the Great Depression was a challenge, America came out of it and World War II as one of the two global superpowers. In the second half of the 1900s, as the U.S. competed with the Soviet Union during the Cold War, the government invested a lot in science and technology. This led to amazing advances in spaceflight, computing, and biotechnology.

Science, technology, and industry have not only made America economically successful but have also shaped its government, society, education, and culture.

Contents

Early American Technology

Native American Innovations

North America has been lived in for a very long time, since about 4,000 BC. The first people were nomadic hunter-gatherers who came across the Bering land bridge. These early Native Americans used stone spearheads, simple harpoons, and boats made of animal hides for hunting in the Arctic. As they spread across the continent, they found different climates.

People in the Pacific Northwest built wooden houses, used nets to catch fish, and preserved food. People on the plains were mostly nomadic and became skilled leather workers as they hunted buffalo. In the arid Southwest, people built adobe buildings, made pottery, grew cotton, and wove cloth. Tribes in the eastern woodlands and Mississippian Valley had large trade networks, built pyramid-like mounds, and farmed a lot. People in the Appalachian Mountains were expert woodworkers and practiced sustainable forest farming. However, these groups had small populations, and their technology changed very slowly. Native Americans did not domesticate animals for pulling loads or for farming, nor did they develop writing systems or tools made of bronze or iron, unlike people in Europe and Asia.

Colonial Farming and Craftsmanship

In the 1600s, Pilgrims, Puritans, and Quakers came from Europe to escape religious persecution. They brought tools like plowshares, guns, and farm animals like cows and pigs. These early European colonists first grew crops like corn, wheat, rye, and oats to feed themselves. They also made potash and maple syrup to trade.

In the warmer Southern states, large plantations grew crops like sugarcane, rice, cotton, and tobacco. These crops needed a lot of labor, so enslaved African people were brought in to work. Early American farmers weren't self-sufficient; they relied on other farmers, skilled workers, and merchants for tools, to process their crops, and to sell them.

Craftsmanship grew slowly in the colonies because there wasn't a big demand for highly skilled work. American artisans used a more relaxed version of the European apprenticeship system to train new workers. Even though the economy focused on exporting raw materials, craftsmen and merchants became more dependent on each other for their businesses. In the mid-1700s, British attempts to control the colonies through taxes made these artisans unhappy, and many joined the Patriot cause.

Factories and Mills Begin

In the 1780s, Oliver Evans invented an automated flour mill that used a grain elevator and a hopper boy. This design eventually replaced older gristmills. By 1800, Evans also created one of the first high-pressure steam engines and set up workshops to build and fix these popular machines.

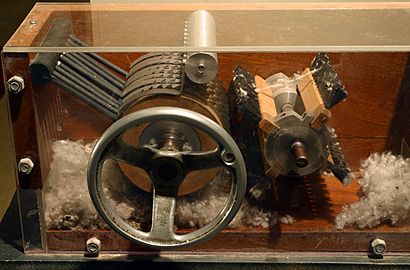

In 1789, Eli Whitney was asked to create a machine to separate cotton seeds from the fibers. His cotton gin could be made with simple carpentry skills, but it reduced the labor needed by 50 times! This made huge profits for cotton growers in the South. Whitney didn't make much money from the gin, but he went on to make rifles and other weapons for the government. He aimed for "expedition, uniformity, and exactness," which were key ideas for interchangeable parts. However, it took over 20 years for interchangeable parts to be fully used in firearms and even longer for other items.

Between 1800 and 1820, new industrial tools greatly improved manufacturing quality and speed. Simeon North suggested using division of labor to make pistols faster, leading to the development of a milling machine in 1798. In 1819, Thomas Blanchard created a lathe that could cut irregular shapes reliably, useful for making weapons. By 1822, Captain John H. Hall developed a system using machine tools, division of labor, and unskilled workers to produce a breech-loading rifle. This process became known as "Armory practice" in the U.S. and the American system of manufacturing in England.

The textile industry also had great potential for machines. In the late 1700s, England developed the spinning jenny, water frame, and spinning mule, which made textile production much more efficient. The British government tried to keep these technologies secret. However, Samuel Slater, who had worked in English textile factories, came to the U.S. in 1789. With help from Moses Brown, Slater opened America's oldest cotton-spinning mill with a fully mechanized water power system at the Slater Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island in 1793.

Later, Francis Cabot Lowell and other businessmen set up mills in Waltham, Massachusetts, using water power from the Charles River. Their idea was to have all parts of production, from raw materials to finished fabrics, in one place. This was very efficient. In 1821, the Boston Manufacturing Company built a big expansion in East Chelmsford, which became Lowell, Massachusetts. This city then dominated cloth production for decades.

Slater's business model, called the "Rhode Island System," used independent mills and mill villages. But by the 1820s, a more efficient system, the "Waltham System," started to replace it. This system was based on Lowell's copies of British power looms. Lowell's mills were managed by specialized employees, many of whom were unmarried young women known as "Lowell mill girls." These mills were owned by corporations. Unlike earlier forms of labor, the Lowell system made the idea of a wage laborer popular. These young women often worked for a few years to save money before returning home to school or marriage, creating a new sense of independence for women.

Roads and Canals Connect the Nation

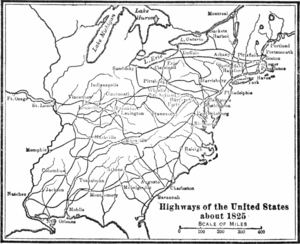

As the U.S. grew with new states like Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio, transportation between these inland states and the coast was difficult. Leaders realized that good roads and canals, like those in the Roman Empire, could unite the country.

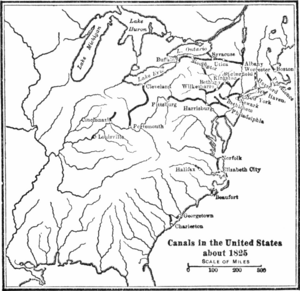

Early toll roads were built by private companies that sold stock to raise money. In 1808, Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin suggested the federal government should fund interstate roads and canals. Many people opposed this, but the British blockade in the War of 1812 showed how important these roads were for military operations and trade. Construction on the National Road began in 1815 and became a main route through the Appalachian Mountains for thousands of settlers moving west.

Many canal companies were also started. The Erie Canal, proposed by Governor of New York DeWitt Clinton, was the first canal project funded by the public. When it was finished in 1825, the canal linked Lake Erie with the Hudson River through 83 locks and over 363 miles (584 km). The success of the Erie Canal led to a boom in canal building across the country. Over 3,326 miles (5,353 km) of artificial waterways were built between 1816 and 1840. Small towns along major canal routes, like Syracuse, New York, Buffalo, New York, and Cleveland, Ohio, grew into big industrial and trade centers.

However, the transportation problem was so big that neither states nor private companies could meet the demands of growing trade. In 1816, President James Madison asked Congress to consider a "comprehensive system of roads and canals." A bill was proposed to use money from the National Bank for internal improvements, but Madison vetoed it, saying it was unconstitutional. This slowed down federal involvement in building roads and canals for a while.

Steamboats Revolutionize Water Travel

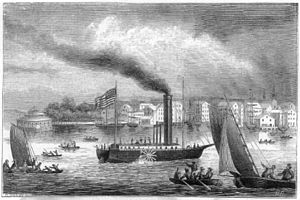

Even with new roads and canals, travel was still slow and costly. The idea of using steam power for boats came from John Fitch and James Rumsey in the late 1780s. But their early steamboats were too complex and expensive. About 20 years later, Robert R. Livingston hired Robert Fulton to develop an affordable steamboat. Fulton's paddle steamer, North River Steamboat (also called the Clermont), made its first trip from New York City to Albany, New York on August 17, 1807.

By 1820, steamboat services were available on all Atlantic rivers and the Chesapeake Bay. The shallow-bottomed boats were also perfect for the Mississippi River and Ohio River. The number of boats on these rivers grew from 17 in 1817 to 727 in 1855. Steamboats cut travel times between coastal ports and upstream cities by weeks and reduced costs for transporting goods by as much as 90%.

Steamboats also changed the relationship between the federal government, state governments, and private businesses. Livingston and Fulton had a monopoly to operate steamboats in New York. But in 1824, the Supreme Court ruled in Gibbons v. Ogden that Congress could regulate trade and transportation under the Commerce Clause. This meant New York had to allow steamboat services from other states.

Because people didn't fully understand how boilers worked, steamboats often had boiler explosions that killed hundreds of people between the 1810s and 1840s. In 1838, a law was passed requiring boiler inspections by federal agents. This showed that many Americans believed property rights did not outweigh civil rights, setting a precedent for future federal safety regulations.

Modern Industrial Growth

Railroads Connect the Country

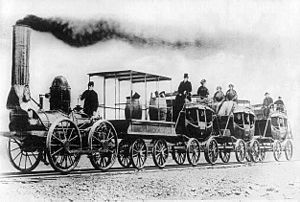

Between 1820 and 1830, inventors started applying steamboat technology to engines that could travel on land. By the mid-1830s, several companies were using steam-powered locomotives to move train cars on rail tracks. Between 1840 and 1860, the total length of railroad tracks grew from 3,326 miles (5,353 km) to 30,600 miles (49,246 km). Railroads made it much cheaper to move large, heavy goods, which hurt the profitability of earlier turnpikes and canals.

However, early railroads were not well connected. There were hundreds of competing companies using different gauges (widths) for their tracks. This meant cargo often had to be moved from one train to another when changing lines.

The completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 led to a period of intense growth and standardization in railroads. Powerful railroad leaders like Jay Gould and Cornelius Vanderbilt combined smaller rail lines into huge national companies. By 1920, 254,000 miles (408,773 km) of standard-gauge railroad track had been laid in the U.S., controlled by just seven organizations. The need to synchronize train schedules also led to the introduction of Standard time by railway managers in 1883. Railroads started using diesel locomotives in the 1930s, which completely replaced steam locomotives by the 1950s, making operations cheaper and more reliable.

After World War II, many railroads struggled due to competition from airlines and Interstate highways. The rise of the automobile led to the end of most passenger train service. Trucking businesses also became major competitors as paved roads improved.

In 1970, the Penn Central railroad went bankrupt. In response, Congress created Amtrak to take over passenger lines. In 1980, the Staggers Rail Act helped revive freight traffic by removing strict rules, making railroads more competitive. More railroad companies merged, leading to the current system of fewer, but profitable, large railroads covering vast regions. To replace lost commuter service, local governments created their own commuter rail systems. The first rapid transit systems opened in Chicago (1892), Boston (1897), and New York City (1904).

Iron and Steel Production

Iron is found in nature as an oxide and must be heated to remove oxygen. Early bloomery forges in the colonies could make small amounts of iron for local needs (like horseshoes and axeblades). Blast furnaces, which made cast iron and pig iron, appeared on large plantations in the mid-1600s. But production was expensive and needed a lot of labor: forests had to be cleared for charcoal, and iron ore and limestone had to be mined. By the late 1700s, the English started using coke, a fuel from coal, to fire their furnaces, which was cheaper. The U.S. later adopted this practice.

Steel is an alloy of iron and a small amount of carbon. Historically, steel was much more expensive than wrought iron. The main challenge was reaching steel's higher melting point for large-scale production. This changed when methods were developed to blow air or oxygen through molten pig iron to remove carbon and impurities, directly turning it into molten steel.

In the 1850s, American William Kelly and Englishman Henry Bessemer independently discovered that blowing air through molten iron increased its temperature and improved its quality. This Kelly-Bessemer process revolutionized the mass production of high-quality steel, drastically lowering its prices and making it widely available.

In 1868, Andrew Carnegie saw an opportunity to combine new coke-making methods with the Kelly-Bessemer process to supply steel for railroads. In 1872, he built a steel plant in Braddock, Pennsylvania, where several major railroad lines met. Carnegie made huge profits by pioneering "vertical integration." He owned the iron ore mines in Minnesota, the steamboats on the Great Lakes, the coal mines and coke ovens, and the rail lines that delivered materials to his mills. By 1900, the Carnegie Steel Company produced more steel than all of Britain. In 1901, Carnegie sold his business to J.P. Morgan's U.S. Steel, making Carnegie $480 million personally.

Telegraph and Telephone Connect People

The ability to send information quickly over long distances had a huge impact on journalism, banking, and diplomacy. Between 1837 and 1844, Samuel F.B. Morse and Alfred Vail developed a transmitter that could send "short" or "long" electric currents. These currents moved an electromagnetic receiver to record signals as dots and dashes. Morse set up the first telegraph line between Baltimore and Washington, D.C. in 1844. By 1849, almost every state east of the Mississippi had telegraph service.

Between 1850 and 1865, the telegraph business became more consolidated. In 1866, Western Union formed, gaining a near-monopoly with over 22,000 telegraph offices and 827,000 miles (1,330,935 km) of cable. The telegraph was used to send news from wars, coordinate troop movements during the Civil War, relay stock prices, and conduct diplomatic talks after the Transatlantic telegraph cable was laid in 1866.

Alexander Graham Bell patented a device in 1876 that could transmit and reproduce the sound of a voice over electrical cables. Bell realized the huge potential of his telephone and formed the Bell Telephone Company. This company controlled the entire system, from making phones to leasing equipment to customers and operators. Between 1877 and 1893 (when Bell's patent expired), the number of phones leased by Bell's company grew from 3,000 to 260,000. These were mostly used by businesses and government offices because of the high costs. After Bell's patents expired, thousands of independent companies started, and their competition drove prices down significantly for middle-class homes and farmers. By 1920, there were 13 million phones in the U.S.

Petroleum Fuels New Industries

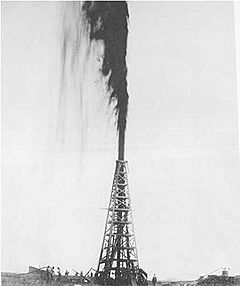

The discovery of crude oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania in 1859 started an "oil rush" similar to the 1849 California Gold Rush. This oil became a valuable resource just before the American Civil War. Because crude oil needs to be distilled to get usable fuel oils, oil refining quickly became a major industry. However, the rural and mountainous areas of these Pennsylvania oilfields made it hard to refine oil on-site or transport it efficiently by railroad.

Starting in 1865, oil pipelines were built to connect oilfields with railroads or refineries. This solved the transportation problem but also put thousands of coopers (barrel makers) and teamsters (wagon drivers) out of business. As the pipeline network grew, it connected with railway and telegraph systems, allowing even better coordination in production, scheduling, and pricing.

John D. Rockefeller was a key figure in combining the American oil industry. Starting in 1865, he bought refineries, railroads, pipelines, and oilfields, and aggressively eliminated competition to his Standard Oil company. By 1879, he controlled 90% of the oil refined in the U.S. Standard Oil used pipelines to directly connect oilfields to refineries, which was much more efficient than loading and unloading railroad tank cars.

Because laws limited how corporations could do business across state lines, Standard Oil pioneered the use of a central trust that owned and controlled its companies in each state. Other industries used trusts to stop competition, leading to the 1890 passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act. In 1911, the Supreme Court ordered Standard Oil to break up into competing companies, which became Exxon, Mobil, and Chevron.

Demand for petroleum products grew quickly as families used kerosene for heat and light, industries used lubricants for machines, and the growing number of internal combustion engines needed gasoline fuel. Between 1880 and 1920, the amount of oil refined annually jumped from 26 million to 442 million barrels. The discovery of large oil fields in Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and California in the early 1900s led to "oil crazes" and helped these states industrialize rapidly. Cities like Long Beach, California, Dallas, Texas, and Houston, Texas became major centers for refining and managing these new fields under companies like Sunoco, Texaco, and Gulf Oil.

Electricity Lights Up America

Benjamin Franklin was a pioneer in studying electricity. He was the first to describe positive and negative charges and the idea that charge is conserved. He is famous for his kite experiment, which showed that lightning is a form of electricity, leading to the invention of the lightning rod to protect buildings.

Electricity remained a novelty for a long time, but advances in battery storage, generation, and lighting turned it into a common household item. By the late 1870s and early 1880s, central power plants supplying power to arc lamps started spreading rapidly, first in Europe and then in the U.S. These systems used very high voltage direct current or alternating current for outdoor lighting, replacing oil and gas. In 1880, Thomas Edison developed and patented a system for indoor lighting that competed with gas lighting. It was based on a long-lasting, high-resistance incandescent light bulb that ran on relatively low voltage (110 volt) direct current.

Edison's small laboratory couldn't handle the huge task of making this a commercial success. It required setting up a large, investor-backed utility that included companies to manufacture the entire system: generators (Edison Machine Works), cables (Edison Electric Tube Company), generating plants and electric service (Edison Electric Light Company), sockets, and bulbs.

Besides lighting, electric motors became extremely important for industry. These motors, which use electricity to spin a magnet and perform work, eventually replaced steam engines in factories. They didn't need complex mechanical systems from a central engine or water for steam boilers.

Edison's direct current (DC) system dominated early indoor electric lighting. However, DC transmission was limited because it was hard to change voltages between industrial generation and home use, and low voltages lost power over long distances. In the mid-1880s, the transformer was introduced, allowing alternating current (AC) to be transmitted at high voltage over long distances more efficiently. AC could then be "stepped down" to supply homes and businesses. This led to AC taking over the domestic lighting market that Edison's DC system was designed for.

The rapid spread of AC and messy power line installations, especially in New York City, led to deaths attributed to high voltage AC. This caused a media backlash. Starting in 1888, the Edison company emphasized the dangers of AC power. This period became known as the "war of the currents." However, Edison's company continued to lose market share to AC-based companies. In 1892, the "war" ended when Thomas Edison lost control of his company. It merged with Westinghouse's main AC rival, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company, to form General Electric, which controlled three-quarters of the U.S. electrical business.

As in other industries, these companies merged to become larger, more efficient "conglomerated" companies. From over a dozen electric companies in the 1880s, only two remained: General Electric and Westinghouse. Electric lighting was incredibly popular: between 1882 and 1920, the number of generating plants in the U.S. grew from one in Downtown Manhattan to nearly 4,000. By 1920, electricity had surpassed petroleum-based lighting sources.

Automobiles Change Travel

The technology for creating an automobile emerged in Germany in the 1870s and 1880s. Nicolaus Otto created a four-stroke internal combustion engine, Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhelm Maybach made it run faster, and Karl Benz pioneered the electric ignition. The Duryea brothers and Hiram Percy Maxim were among the first to build a "horseless carriage" in the U.S. in the mid-1890s, but these early cars were heavy and expensive.

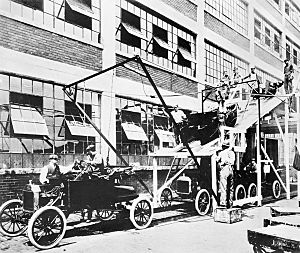

Henry Ford revolutionized car manufacturing by using interchangeable parts on assembly lines. This was the beginning of industrial mass production. In 1908, the Ford Motor Company released the Ford Model T. It was lightweight, easy to repair, and had 20 horsepower. Demand for the car was so high that Ford had to move his plant to Highland Park, Michigan in 1912. The new plant was a model of industrial efficiency: it was well-lit, ventilated, used conveyors to move parts, and workers' stations were neatly arranged.

The efficiency of the assembly line allowed Ford to make huge gains in economy and productivity. In 1912, Ford sold 6,000 cars for about $900. By 1916, about 577,000 Model T automobiles were sold for $360. Ford could increase production quickly because assembly-line workers were unskilled laborers doing repetitive tasks. Ford hired European immigrants, African-Americans, ex-convicts, and people with disabilities, and paid relatively high wages.

As more Americans used cars, urban and rural roads were improved. Local automobile clubs formed the American Automobile Association to push city, state, and federal governments to widen and pave existing roads and build new highways. Some federal road aid was passed in the 1910s and 20s, leading to highways like U.S. Route 1 and U.S. Route 66. Road quality greatly improved after the Depression-era Works Progress Administration invested in road infrastructure.

New car sales slowed during World War II due to wartime rationing and military production. After the war, growing families, increasing wealth, and government-subsidized mortgages for veterans fueled a boom in single-family homes, many owned by car owners. In 1956, Congress passed the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, which funded the construction of 41,000 miles (66,000 km) of toll-free expressways across the country. This laid the foundation for the modern American highway system.

Impact of Industrialization

Changes in Farming

In the 1840s, as more western states joined the Union, many poor and middle-class Americans wanted free land in these undeveloped areas. The Homestead Act was passed in 1862. It gave 160 acres (65 hectares) to farmers who lived on the land for 5 years, or allowed them to buy it after 6 months for $1.25 per acre ($3/ha).

Even as over 400 million acres (1,600,000 km2) of new land were farmed, the number of Americans involved in farming dropped by a third between 1870 and 1910. New farming techniques and machines made this possible. Cyrus McCormick's reaper (invented in 1834) allowed farmers to harvest four times more efficiently by replacing hand labor with a machine. John Deere invented the steel plow in 1837, which kept soil from sticking and made farming easier in the rich prairies of the Midwest. The harvester, self-binder, and combine allowed even greater efficiencies.

Railroads allowed harvests to reach markets more quickly. Gustavus Franklin Swift's refrigerated railroad car allowed fresh meat and fish to reach distant markets. Food distribution also became more mechanized as companies like Heinz and Campbell canned and evaporated perishable foods. Commercial bakeries, breweries, and meatpackers replaced local operators and increased demand for raw farm goods. Despite rising demand, increased production caused prices to drop, making farmers unhappy. Organizations like The Grange and Farmers Alliance formed to demand changes like easier money supply and railroad regulations.

Growth of Cities

The period between 1865 and 1920 saw more and more people, political power, and economic activity concentrated in cities. In 1860, there were nine cities with over 100,000 people. By 1910, there were fifty. These new large cities were often inland, along new transportation routes (like Denver, Chicago, and Cleveland), not just coastal ports.

Industrialization and urbanization fed each other. Cities became very crowded. Due to unsanitary living conditions, diseases like cholera, dysentery, and typhoid fever became common. Cities responded by paving streets, digging sewers, sanitizing water, building housing, and creating public transportation systems.

Labor and Immigration

As the nation's technology grew, old-fashioned artisans and craftsmen were replaced by specialized workers and engineers who used machines. Frederick Winslow Taylor suggested that by studying the motions and processes needed to make each part of a product, reorganizing factories around workers, and paying workers based on how much they produced, efficiency could greatly increase. This "Taylorism" was soon applied to city governments and even home economics.

Increased industrialization created a demand for laborers willing to work in dangerous, low-paying jobs. This demand drove wages up and attracted waves of Irish, Italian, Polish, Russian, and Jewish immigrants who could earn more in America than in their home countries.

The earliest unions formed before the Civil War as groups of skilled workers who would go on strikes to demand better hours and pay. Generally, all parts of the government tried to stop labor from forming unions or organizing strikes.

Government Regulation

The Progressive movement that emerged was partly a reaction to the problems caused by the new industrial age. "Muckraking" journalists reported on social issues, and public reaction led to reforms and increased government regulation. Examples include the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 (for railroads) and the Meat Inspection Act and Pure Food and Drug Act (1906), which aimed to protect consumers.

Science, Military, and Universities

Research Universities Grow

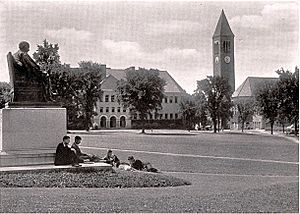

The first universities in the United States were based on the liberal arts education of English universities. They were meant to train clergymen and lawyers, not teach practical skills or conduct scientific research. The U.S. Military Academy, established in 1811, was different. It included practical engineering subjects in its early courses. By the mid-1800s, more polytechnic institutes were founded to train students in the scientific and technical skills needed to design, build, and operate complex machines.

In 1862, Congress passed the Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act. This law provided large grants of land to establish and fund educational institutions that would teach military tactics, engineering, and agriculture. Many of the United States' noted public research universities started as land-grant colleges. Between 1900 and 1939, college enrollments greatly increased, and higher education became more available and affordable. A college degree became increasingly necessary for scientific, engineering, and government jobs that previously only required vocational or secondary education.

After World War II, the GI Bill caused university enrollments to explode as millions of veterans earned college degrees.

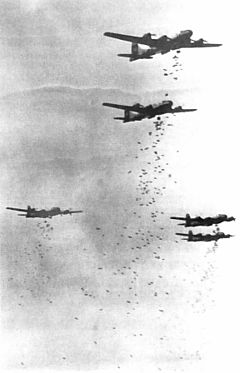

Technology in World Wars

The introduction of the airplane to the battlefield was one of the most radical changes in warfare. In December 1903, the Wright brothers achieved sustained, piloted, and controlled flight. The Wright brothers had trouble getting funding from the government, but after World War I began in 1914, airplanes quickly became very important for both sides. The U.S. government spent $640 million in 1917 to get 20,000 airplanes for aerial reconnaissance, dogfighting, and aerial bombing.

After the war ended in 1918, the U.S. government continued to fund peacetime aviation activities like airmail and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, industrial, university, and military research improved the power, maneuverability, and reliability of airplanes. Charles Lindbergh completed a solo non-stop transatlantic flight in 1927, and Wiley Post flew around the world in nine days in 1931. In the 1930s, passenger airlines boomed, and state and local governments built airports. The federal government began to regulate air traffic control and investigate aviation accidents and incidents.

Cold War and Space Race

American physicist Robert H. Goddard was one of the first scientists to experiment with rocket propulsion systems. In his small laboratory, Goddard worked with liquid oxygen and gasoline to propel rockets. In 1926, he successfully fired the world's first liquid-fuel rocket, which reached a height of 12.5 meters. Over the next 10 years, Goddard's rockets reached modest altitudes, and interest in rocketry grew in the United States, Britain, Germany, and the Soviet Union.

At the end of World War II, both American and Russian forces recruited top German scientists like Wernher von Braun to continue defense-related work. Rockets provided the means for launching artificial satellites and crewed spacecraft. In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the first satellite, Sputnik I, and the United States followed with Explorer I in 1958. The first crewed space flights were made in early 1961, first by Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin and then by American astronaut Alan Shepard.

From those first steps to the 1969 Apollo program landing on the Moon, and to the reusable Space Shuttle, the American space program has shown amazing applied science. Communications satellites transmit computer data, telephone calls, and radio and television broadcasts. Weather satellites provide data for early warnings of severe storms.

Technology and Society

Computers and Information Networks

American researchers made fundamental advances in telecommunications and information technology. For example, AT&T's Bell Laboratories led the American technological revolution with inventions like the LED, the transistor, the C programming language, and the UNIX computer operating system. SRI International and Xerox PARC in Silicon Valley helped create the personal computer industry. ARPA and NASA funded the development of the ARPANET and the Internet.

Companies like IBM and Apple Computer developed personal computers, while Microsoft created operating systems and office software to run on them. With the growth of information on the World Wide Web, search companies like Yahoo! and Google developed technologies to sort and rank web pages. The web also became a place for social interactions, and services like MySpace, Facebook, and Twitter are used by millions to communicate. The miniaturization of computing technology and the increasing spread and speed of wireless networks led to widespread adoption of mobile phones and powerful smartphones based on software platforms like Apple's iOS and Google's Android.

See also

In Spanish: Historia tecnológica e industrial de Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Historia tecnológica e industrial de Estados Unidos para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |