Late Middle Ages facts for kids

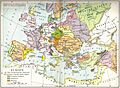

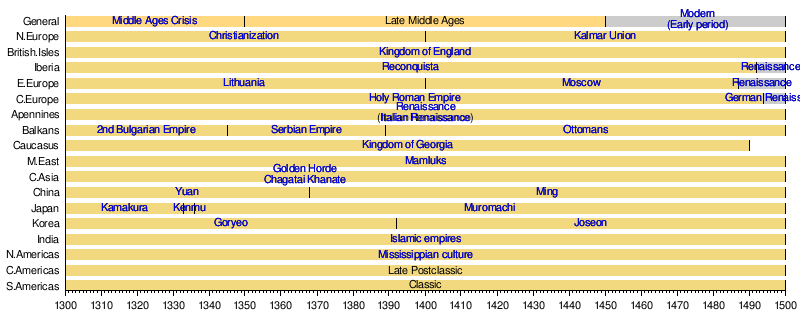

The Late Middle Ages was a time in European history from about 1300 to 1500 AD. It came after the High Middle Ages and before the start of the early modern period, which included the Renaissance in many parts of Europe.

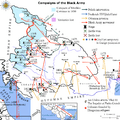

Around 1300, a long period of growth and wealth in Europe slowed down. Many famines (times when there wasn't enough food) and plagues (widespread diseases), like the Great Famine of 1315–1317 and the terrible Black Death, caused the population to drop by about half. With fewer people, there was also a lot of social unrest and constant fighting. Countries like France and England saw big peasant uprisings, such as the Jacquerie and the Peasants' Revolt. They also fought each other for over a century in the Hundred Years' War. On top of these problems, the Catholic Church was temporarily split by the Western Schism, where there were two popes at once. All these events together are sometimes called the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages.

Despite these tough times, the 14th century was also a period of great progress in art and science. People became interested again in old Greek and Roman writings, which led to the start of the Italian Renaissance. Many Greek scholars came to Italy after the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire, bringing their knowledge with them.

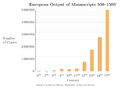

A huge invention during this time was the printing press. It made it much easier to share books and ideas, helping more people learn. This, along with new classical ideas, later led to the Reformation, a big change in the Christian church. Towards the end of this period, the Age of Discovery began. The growing Ottoman Empire made trade with the East difficult, so Europeans looked for new routes. This led to Christopher Columbus's voyage to the Americas in 1492 and Vasco da Gama's trip around Africa to India in 1498. These discoveries made European nations stronger and richer.

These big changes made many historians see this period as the end of the Middle Ages and the start of modern history. However, the change wasn't sudden, as old knowledge was always present in Europe. Some historians, especially in Italy, prefer to see the High Middle Ages simply leading into the Renaissance and the modern era.

Contents

European History in the Late Middle Ages

During the 14th and 15th centuries, the borders of Christendom (Christian Europe) were still changing. The Grand Duchy of Moscow began to push back the Mongols, and the kingdoms in Spain and Portugal finished their Reconquista (reconquest) of the peninsula from Muslim rule and started looking outwards. Meanwhile, the Balkans region fell under the control of the Ottoman Empire. Other European nations were often fighting each other or dealing with internal conflicts.

This situation slowly led to stronger central governments and the rise of nation-states. Wars cost a lot of money, so rulers needed to collect more taxes. This led to the creation of representative groups, like the English Parliament, which gave people more say. The power of kings also grew as the Papacy (the Pope's power) declined with the Western Schism and the start of the Protestant Reformation.

Northern Europe

After a failed attempt to unite Sweden and Norway (1319–1365), the Kalmar Union was formed in 1397, bringing together all the Scandinavian countries. Sweden was never happy being part of this union, which was mostly controlled by Denmark. In 1520, the Danish king Christian II of Denmark tried to control the Swedes by killing many Swedish nobles in the Stockholm Bloodbath. But this only made things worse, and Sweden finally broke away in 1523. Norway, however, remained part of the union with Denmark until 1814.

Iceland was lucky because it was isolated, so the Black Death arrived there later than in other Scandinavian countries. Sadly, the Norse colony in Greenland died out, probably because of very cold weather in the 15th century, possibly due to the Little Ice Age.

Northwest Europe

When Alexander III of Scotland died in 1286, it caused a problem over who would be the next king. The English king, Edward I, was asked to help decide. Edward then claimed to be the ruler of Scotland, which led to the Wars of Scottish Independence. In the end, the English were defeated, and Scotland became a stronger country under the Stewarts.

From 1337, England focused mostly on its war with France, known as the Hundred Years' War. Henry V's big victory at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 almost united the two kingdoms. But his son, Henry VI, soon lost all the gains. Losing France caused unhappiness back home. Soon after the war ended in 1453, the Wars of the Roses (around 1455–1485) began. This was a fight between two powerful English families, the House of Lancaster and the House of York, for the throne.

The war ended when Henry VII from the House of Tudor became king. He continued to build a strong, central government. While England was busy with these wars, the Hiberno-Norman lords in Ireland became more like Irish society. This allowed Ireland to become almost independent, even though England was still officially in charge.

Western Europe

The House of Valois family took over the French throne in 1328 after the House of Capet. At first, they had little power in their own country. They faced invasions from England during the Hundred Years' War and also had to deal with the powerful Duchy of Burgundy. But then, Joan of Arc emerged as a military leader, changing the war in France's favor. King Louis XI continued this success.

Meanwhile, Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy, struggled to unite his lands. He faced strong resistance, especially from the Swiss Confederation, which formed in 1291. When Charles was killed in the Burgundian Wars at the Battle of Nancy in 1477, France took back the Duchy of Burgundy. At the same time, the County of Burgundy and the rich Burgundian Netherlands became part of the Holy Roman Empire under the Habsburg family. This set the stage for conflicts that would last for centuries.

Central Europe

Bohemia was very successful in the 14th century. The Golden Bull of 1356 made the King of Bohemia the most important among the imperial electors who chose the Holy Roman Emperor. However, the Hussite Wars later caused a crisis in the country. The Holy Roman Empire then passed to the House of Habsburg in 1438 and stayed with them until it ended in 1806. Even though the Habsburgs controlled huge areas, the Empire itself remained divided, and much real power belonged to individual princes. Also, powerful financial groups like the Hanseatic League and the Fugger family held great economic and political influence.

The Kingdom of Hungary had a golden age in the 14th century. The reigns of kings Charles Robert (1308–42) and his son Louis the Great (1342–82) were especially successful. Hungary became rich as Europe's main supplier of gold and silver. Louis the Great led successful military campaigns from Lithuania to Southern Italy and from Poland to Northern Greece. He had the largest army of the 14th century, often with over 100,000 soldiers. Meanwhile, Poland focused on the East. Its union with Lithuania created a huge country in the region. This union, and Lithuania becoming Christian, also marked the end of paganism in Europe.

Louis the Great died in 1382 without a son to inherit his throne. He named the young prince Sigismund of Luxemburg as his heir. However, the Hungarian nobles did not accept this, leading to an internal war. Sigismund eventually gained full control of Hungary and set up his court in Buda and Visegrád. These palaces were rebuilt and improved, becoming some of the richest in Europe at the time. Sigismund also inherited the thrones of Bohemia and the Holy Roman Empire, but he continued to rule from Hungary. He was kept busy fighting the Hussites and the Ottoman Empire, which became a threat to Europe in the early 15th century.

King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary led the largest mercenary army of his time, called the Black Army of Hungary. He used this army to conquer Bohemia and Austria and to fight the Ottoman Empire. After Italy, Hungary was the first European country where the Renaissance appeared. However, the glory of the Kingdom ended in the early 16th century when King Louis II of Hungary was killed in the Battle of Mohács in 1526 against the Ottoman Empire. Hungary then faced a serious crisis and was invaded, ending its importance in central Europe during the medieval era.

Eastern Europe

The state of Kievan Rus' fell during the 13th century due to the Mongol invasion. After this, the Grand Duchy of Moscow grew in power. It won a big victory against the Golden Horde (a Mongol group) at the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380. However, this victory didn't end Mongol rule right away. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania benefited more immediately, expanding its influence eastward.

Under the rule of Ivan the Great (1462–1505), Moscow became a major power in the region. When it took over the large Republic of Novgorod in 1478, it laid the groundwork for a Russian national state. After the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, Russian princes began to see themselves as the successors to the Byzantine Empire. They eventually took the imperial title of Tsar, and Moscow was called the Third Rome.

Southeast Europe

The Byzantine Empire had long been a dominant power in the eastern Mediterranean in terms of politics and culture. But by the 14th century, it had almost completely fallen apart. It became a state that paid tribute to the Ottoman Empire, with its power centered around the city of Constantinople and a few small areas in Greece. When Constantinople fell in 1453, the Byzantine Empire was completely gone.

The Second Bulgarian Empire was also declining by the 14th century. The rise of Serbia was marked by their victory over the Bulgarians in the Battle of Velbazhd in 1330. By 1346, the Serbian king Stefan Dušan had even declared himself emperor. But Serbian power didn't last long. The Serbian army, led by Lazar Hrebeljanovic, was defeated by the Ottoman Army at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. Most of the Serbian nobility were killed, and the southern part of the country came under Ottoman control, just as much of southern Bulgaria had after the Battle of Maritsa in 1371. The remaining northern parts of Bulgaria were conquered by 1396. Serbia fell in 1459, Bosnia in 1463, and Albania was finally taken over in 1479, a few years after the death of Skanderbeg. Belgrade, which was part of Hungary at the time, was the last major Balkan city to fall to the Ottomans, in the siege of Belgrade in 1521. By the end of the medieval period, the entire Balkan peninsula was either taken over by or became a vassal (a state controlled by) the Ottomans.

Southwest Europe

Avignon in France was the home of the papacy from 1309 to 1376. When the Pope returned to Rome in 1378, the Papal State (the Pope's own territory) grew into a major secular power. This reached its peak with the morally corrupt papacy of Alexander VI. Florence became very important among the Italian city-states because of its financial business. The powerful Medici family became big supporters of the Renaissance by paying for many artists. Other city-states in northern Italy also expanded their lands and power, especially Milan, Venice, and Genoa. The War of the Sicilian Vespers had, by the early 14th century, divided southern Italy into an Aragon-controlled Kingdom of Sicily and an Anjou-controlled Kingdom of Naples. In 1442, these two kingdoms were effectively united under Aragonese rule.

The marriage of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1469, and the death of John II of Aragon in 1479, led to the creation of modern-day Spain. In 1492, Granada was captured from the Moors (Muslim rulers), completing the Reconquista. Portugal had, during the 15th century (especially under Henry the Navigator), slowly explored the coast of Africa. In 1498, Vasco da Gama found the sea route to India. The Spanish monarchs responded to Portugal's success by funding Christopher Columbus's expedition to find a western sea route to India, which led to the discovery of the Americas in 1492.

Life in Late Medieval Europe

Around 1300–1350, the Medieval Warm Period ended, and the Little Ice Age began, bringing colder weather. This colder climate led to problems with farming, the first of which was the Great Famine of 1315–1317. However, the number of deaths from this famine was not as high as those caused by the plagues that came later in the century, especially the Black Death. It's estimated that the Black Death killed between one-third and sixty percent of the population. By about 1420, the combined effect of repeated plagues and famines had reduced Europe's population to perhaps only a third of what it had been a century earlier. Wars made the effects of these natural disasters even worse, especially in France during the Hundred Years' War. It took 150 years for Europe's population to return to the levels of 1300.

Because the European population was so much smaller, there was more land available for the people who survived, and labor became more expensive. Landowners tried to force wages down, like with the English 1351 Statute of Laborers, but these efforts failed. Instead, they made peasants angry, leading to rebellions like the French Jacquerie in 1358 and the English Peasants' Revolt in 1381. The long-term result was that serfdom (a system where peasants were tied to the land) mostly ended in Western Europe. In Eastern Europe, however, landowners used the situation to force peasants into even stricter forms of bondage.

The chaos caused by the Black Death made some minority groups especially vulnerable, particularly Jews, who were often blamed for the disasters. Anti-Jewish attacks called pogroms happened all over Europe. For example, in February 1349, 2,000 Jews were killed in Strasbourg. Governments also discriminated against Jews. Rulers gave in to public demands, and Jews were expelled from England in 1290, from France in 1306, from Spain in 1492, and from Portugal in 1497.

While Jews faced persecution, women likely gained more power in the Late Middle Ages. The big social changes of the period created new opportunities for women in business, learning, and religion. However, at the same time, women were also at risk of being accused and persecuted, as belief in witchcraft grew.

The combination of social, environmental, and health problems also led to an increase in violence in most parts of Europe. More people, religious intolerance, famine, and disease led to more violent acts in much of medieval society. One exception was North-Eastern Europe, where the population managed to keep violence low due to a more organized society that resulted from extensive and successful trade.

Until the mid-14th century, Europe had seen a steady increase in urbanisation (people moving to cities). Cities were also hit hard by the Black Death, but their role as centers for learning, trade, and government ensured they continued to grow. By 1500, cities like Venice, Milan, Naples, Paris, and Constantinople probably had over 100,000 people each. Twenty-two other cities had more than 40,000 people; most of these were in Italy and the Iberian Peninsula, but some were also in France, the Holy Roman Empire, the Low Countries, and London in England.

Military Changes

Battles like Courtrai (1302), Bannockburn (1314), and Morgarten (1315) showed European rulers that the old advantage of cavalry (knights on horseback) was gone. A well-equipped infantry (foot soldiers) was now better. Through the Welsh Wars, the English learned about and adopted the very effective longbow. When used properly, this weapon gave them a big advantage over the French in the Hundred Years' War.

The invention of gunpowder greatly changed how wars were fought. Although the English used firearms as early as the Battle of Crécy in 1346, they didn't have much effect on the battlefield at first. The biggest change came from using cannons as siege weapons (to attack castles and walled cities). These new methods eventually changed how fortifications (castles and walls) were built.

Changes also happened in how armies were recruited and what they were made of. The old system of calling up national or feudal armies was slowly replaced by paid soldiers, either from a ruler's own retinue (personal followers) or foreign mercenaries. This practice was linked to Edward III of England and the condottieri (mercenary leaders) of the Italian city-states. All over Europe, Swiss soldiers were especially sought after. At the same time, this period also saw the first permanent armies. It was in Valois France, under the heavy demands of the Hundred Years' War, that armies slowly became permanent.

Along with military changes, a more detailed code of conduct for knights, called chivalry, developed. This new set of values can be seen as a response to the declining military role of the aristocracy. It gradually became almost completely separate from its military origins. The spirit of chivalry was expressed through new (non-religious) chivalric orders. The first of these was the Order of St. George, founded by Charles I of Hungary in 1325. The most famous was probably the English Order of the Garter, founded by Edward III in 1348.

Christian Conflicts and Reforms

The Papal Schism

The French king's growing power over the Papacy (the Pope) led to the Pope moving his official home to Avignon in 1309. When the Pope returned to Rome in 1377, it caused a problem: different popes were elected in Avignon and Rome. This resulted in the Papal Schism (1378–1417). The Schism divided Europe along political lines. France, its ally Scotland, and the Spanish kingdoms supported the Avignon Pope. England, France's enemy, supported the Pope in Rome, along with Portugal, Scandinavia, and most German princes.

At the Council of Constance (1414–1418), the Papacy was finally reunited in Rome. Even though the Western Church remained united for another hundred years, and the Papacy became richer than ever, the Great Schism had caused lasting damage. The Church's internal struggles weakened its claim to rule everyone, and it encouraged anti-clericalism (opposition to the clergy) among people and their rulers, setting the stage for reform movements.

The Protestant Reformation

Even though many of these events happened outside the traditional Middle Ages timeframe, the end of the Western Church's unity (the Protestant Reformation) was a key feature of the medieval period. The Catholic Church had long fought against groups it called heretics, but during the Late Middle Ages, it started to face demands for reform from within. The first of these came from Oxford professor John Wycliffe in England. Wycliffe believed that the Bible should be the only authority in religious matters. He spoke out against transubstantiation (the belief that bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ), celibacy (priests not marrying), and indulgences (paying money to reduce punishment for sins). Despite having powerful supporters among the English nobility, his movement was not allowed to survive. While Wycliffe himself was not harmed, his followers, the Lollards, were eventually suppressed in England.

The marriage of Richard II of England to Anne of Bohemia created links between the two countries and brought Lollard ideas to Bohemia. The teachings of the Czech priest Jan Hus were based on John Wycliffe's ideas. However, his followers, the Hussites, had a much greater political impact than the Lollards. Hus gained many followers in Bohemia. In 1414, he was asked to appear at the Council of Constance to explain his beliefs. When he was burned as a heretic in 1415, it caused a popular uprising in the Czech lands. The following Hussite Wars eventually fell apart due to internal disagreements and did not lead to religious or national independence for the Czechs. However, both the Catholic Church and the German influence within the country were weakened.

Martin Luther, a German monk, started the German Reformation by posting his 95 theses on the church door in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517. He was upset because Pope Leo X was renewing the sale of indulgences to fund the building of the new St. Peter's Basilica. Luther was challenged to take back his ideas at the Diet of Worms in 1521. When he refused, Charles V declared him an outlaw. With the protection of Frederick the Wise, Luther was able to translate the Bible into German.

For many rulers, the Protestant Reformation was a good chance to gain more wealth and power. The Catholic Church responded to these reform movements with what is called the Catholic Reformation, or Counter-Reformation. Europe became split into northern Protestant and southern Catholic parts, leading to the Religious Wars of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Trade and Business

The growing power of the Ottoman Empire in the eastern Mediterranean made trade difficult for Christian nations in the west. So, they started looking for other ways to trade. Portuguese and Spanish explorers found new trade routes – south of Africa to India, and across the Atlantic Ocean to America. As merchants from Genoa and Venice opened direct sea routes to Flanders, the Champagne fairs (big trade markets) lost much of their importance.

At the same time, England started exporting processed cloth instead of just raw wool. This caused losses for cloth makers in the Low Countries. In the Baltic and North Sea, the Hanseatic League (a powerful group of trading cities) reached its peak in the 14th century but began to decline in the 15th.

In the late 13th and early 14th centuries, a "commercial revolution" happened, mainly in Italy and parts of the Holy Roman Empire. New business ideas included new forms of partnership and insurance, which helped reduce the risks of trade. The bill of exchange and other forms of credit helped people trade without carrying large amounts of money and avoided church rules against usury (lending money with interest) for non-Jews. New ways of accounting, especially double-entry bookkeeping, allowed for better tracking of money.

With this growth in finance, trading rights became more closely guarded by rich merchants. Towns saw the growing power of guilds (groups of skilled workers), while at a national level, special companies were given monopolies (exclusive rights) on certain trades, like the English wool Staple. The people who benefited from these changes became incredibly wealthy. Families like the Fuggers in Germany, the Medicis in Italy, the de la Poles in England, and individuals like Jacques Coeur in France helped pay for kings' wars and gained great political influence.

While the population crisis of the 14th century definitely caused a big drop in production and trade, historians have debated whether the decline was worse than the population drop. Some older ideas suggested that the amazing art of the Renaissance came from greater wealth. However, more recent studies have suggested there might have been a "depression of the Renaissance." Despite strong arguments, there isn't enough complete statistical evidence to make a final conclusion.

Arts and Sciences

In the 14th century, the main way of thinking in universities, called scholasticism, was challenged by the humanist movement. Humanism was mostly about bringing back the classical languages (Latin and Greek). But it also led to new ideas in science, art, and literature. This was helped by ideas from Byzantine scholars who came to the west after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

In science, old authorities like Aristotle were questioned for the first time since ancient times. In the arts, humanism led to the Renaissance. While the 15th-century Renaissance was mostly in the city-states of northern Italy, important artistic developments also happened further north, especially in the Netherlands.

Philosophy, Science, and Technology

The main way of thinking in the 13th century was Thomism, which tried to combine Aristotle's teachings with Christian theology. However, the Condemnation of 1277 at the University of Paris put limits on ideas that could be seen as heresy, which affected Aristotelian thought. William of Ockham offered a different approach, following the earlier Franciscan John Duns Scotus. Ockham insisted that the world of reason and the world of faith should be kept separate. He introduced the principle of parsimony, or Occam's razor, which says that a simple theory is better than a complex one, and we should avoid guessing about things we can't observe.

This new way of thinking freed scientific guesses from the strict rules of Aristotelian science and opened the door for new ideas. Great progress was made, especially in theories of motion. Scholars like Jean Buridan, Nicole Oresme, and the Oxford Calculators challenged Aristotle's work. Buridan developed the idea of impetus as the cause of how objects move, which was an important step towards the modern idea of inertia. The work of these scholars hinted at the heliocentric (sun-centered) view of the universe later proposed by Nicolaus Copernicus.

Some technological inventions of this period – whether from Arab or Chinese origins, or new European ideas – had a big impact on politics and society. These included gunpowder, the printing press, and the compass. Gunpowder changed military organization and helped the rise of nation-states. Gutenberg's movable type printing press not only helped the Protestant Reformation but also spread knowledge, leading to a more equal society. The compass, along with other inventions like the cross-staff, the mariner's astrolabe, and better shipbuilding, allowed people to navigate the World Oceans and begin the first stages of colonialism. Other inventions had a greater impact on daily life, such as eyeglasses and the weight-driven clock.

Visual Arts and Architecture

Early signs of Renaissance art can be seen in the early 14th-century works of Giotto. Giotto was the first painter since ancient times to try to show a three-dimensional world and to give his characters real human emotions. However, the most important developments happened in 15th-century Florence. The wealth of the merchant class allowed for a lot of support for the arts, and the Medici family were among the most important patrons.

This period saw several important technical innovations, like the idea of linear perspective found in the work of Masaccio, and later described by Brunelleschi. Artists like Donatello achieved greater realism through the scientific study of anatomy. This can be seen especially well in his sculptures, which were inspired by studying classical models. As the center of the movement moved to Rome, the period reached its peak with the High Renaissance masters da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

The ideas of the Italian Renaissance were slow to cross the Alps into northern Europe, but important artistic innovations also happened in the Low Countries. Although not the inventor of oil painting (as was once believed), Jan van Eyck was a master of the new medium. He used it to create very realistic and detailed works. The two cultures influenced and learned from each other, but painting in the Netherlands remained more focused on textures and surfaces than the idealized compositions of Italy.

In northern European countries, Gothic architecture remained popular, and Gothic cathedrals became even more elaborate. In Italy, however, architecture took a different path, also inspired by classical ideas. The greatest work of the period was the Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, with Giotto's clock tower, Ghiberti's baptistery gates, and Brunelleschi's cathedral dome, which was incredibly large for its time.

Literature

The most important change in late medieval literature was the rise of vernacular languages (the everyday languages spoken by people, not Latin). Vernacular languages had been used in England since the 8th century and France since the 11th century. In these places, popular types of stories included the chanson de geste (epic poems about heroic deeds), troubadour lyrics (songs about love), and romantic epics, or romances. Although Italy was later in developing its own literature in the local language, it was here that the most important literary changes of the period happened.

Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, written in the early 14th century, combined a medieval worldview with classical ideas. Another person who promoted the Italian language was Boccaccio with his Decameron. Using the local language didn't mean rejecting Latin. Both Dante and Boccaccio wrote a lot in Latin as well as Italian, as did Petrarch later (whose Canzoniere also promoted the local language and whose poems are considered the first modern lyric poems). Together, these three poets made the Tuscan dialect the standard for the modern Italian language.

The new literary style spread quickly. In France, it influenced writers like Eustache Deschamps and Guillaume de Machaut. In England, Geoffrey Chaucer helped establish Middle English as a literary language with his Canterbury Tales, which featured many different narrators and stories (including some translated from Boccaccio). The spread of literature in local languages eventually reached Bohemia, and the Baltic, Slavic, and Byzantine worlds.

Music

Music was a big part of both everyday life and religious culture. In universities, it was part of the quadrivium (four subjects) of the liberal arts. From the early 13th century, the main sacred (religious) musical form was the motet, a song with text in several parts. From the 1330s onwards, a polyphonic style emerged, which was a more complex mix of independent voices. Polyphony had been common in the non-religious music of the Provençal troubadours. Many of these troubadours were victims of the 13th-century Albigensian Crusade, but their influence reached the Pope's court at Avignon.

The main composers of this new style, often called ars nova (new art) as opposed to ars antiqua (old art), were Philippe de Vitry and Guillaume de Machaut. In Italy, where the Provençal troubadours had also found refuge, the corresponding period is called trecento, and the leading composers were Giovanni da Cascia, Jacopo da Bologna, and Francesco Landini. A notable reformer of Orthodox Church music from the first half of the 14th century was John Kukuzelis. He also introduced a system of musical notation widely used in the Balkans in the following centuries.

Theatre

In the British Isles, plays were performed in about 127 different towns during the Middle Ages. These local Mystery plays were written in cycles of many plays: York (48 plays), Chester (24), Wakefield (32), and Unknown (42). Many more plays survive from France and Germany from this period, and some type of religious dramas were performed in nearly every European country in the Late Middle Ages. Many of these plays included comedy, devils, villains, and clowns.

Morality plays became a distinct type of drama around 1400 and were popular until 1550. An example is The Castle of Perseverance, which shows mankind's journey from birth to death. Another famous morality play is Everyman. Everyman receives Death's call, tries to escape, and finally accepts his fate. Along the way, he is abandoned by Kindred, Goods, and Fellowship – only Good Deeds goes with him to the grave.

Towards the end of the Late Middle Ages, professional actors started to appear in England and Europe. Richard III and Henry VII both had small groups of professional actors. Their plays were performed in the Great Hall of a nobleman's home, often with a raised platform for the audience at one end and a "screen" for the actors at the other. Also important were Mummers' plays, performed during the Christmas season, and court masques (fancy performances). These masques were especially popular during the reign of Henry VIII, who had a House of Revels built and an Office of Revels established in 1545.

Medieval drama ended due to several reasons, including the weakening power of the Catholic Church, the Protestant Reformation, and the banning of religious plays in many countries. Elizabeth I banned all religious plays in 1558, and the big cycle plays had stopped by the 1580s. Similarly, religious plays were banned in the Netherlands in 1539, the Papal States in 1547, and in Paris in 1548. The end of these plays destroyed the international theatre that had existed and forced each country to develop its own type of drama. It also allowed playwrights to turn to non-religious subjects, and the renewed interest in Greek and Roman theatre gave them the perfect opportunity.

After the Middle Ages

After the Late Middle Ages, the Renaissance spread unevenly across Europe from the south. The intellectual changes of the Renaissance are seen as a bridge between the Middle Ages and the Modern era. Europeans then began an era of world discovery. Along with new classical ideas, the invention of printing made it easier to spread written words and made learning more accessible to everyone. These two things led to the Protestant Reformation. Europeans also found new trading routes, like Columbus's journey to the Americas in 1492, and Vasco da Gama's voyage around Africa to India in 1498. Their discoveries made European nations stronger and richer.

Ottomans and Europe

By the end of the 15th century, the Ottoman Empire had advanced across Southeastern Europe, eventually conquering the Byzantine Empire and taking control of the Balkan states. Hungary was the last stronghold of the Latin Christian world in the East and fought to maintain its rule for two centuries. After the young king Vladislaus I of Hungary died during the Battle of Varna in 1444 against the Ottomans, the Kingdom was put in the hands of Count John Hunyadi, who became Hungary's regent-governor (1446–1453). Hunyadi was considered one of the most important military figures of the 15th century. Pope Pius II gave him the title of Athleta Christi or Champion of Christ because he was seen as the only hope for stopping the Ottomans from moving into Central and Western Europe.

Hunyadi succeeded during the Siege of Belgrade in 1456 against the Ottomans, which was the biggest victory against that empire in decades. This battle became a real Crusade against the Muslims, as peasants were encouraged by the Franciscan friar Saint John of Capistrano, who came from Italy preaching a Holy War. The excitement he created at that time was one of the main reasons for the victory. However, the early death of the Hungarian Lord left Pannonia (Hungary) unprotected and in chaos. In a very unusual event for the Middle Ages, Hunyadi's son, Matthias, was elected as King of Hungary by the Hungarian nobility. For the first time, a member of an aristocratic family (not from a royal family) was crowned king.

King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary (1458–1490) was one of the most important figures of the period. He led military campaigns to the West, conquering Bohemia in response to the Pope's call for help against the Hussite Protestants. Also, to resolve political conflicts with the German emperor Frederick III of Habsburg, he invaded his western lands. Matthew organized the Black Army of mercenary soldiers; it was considered the biggest army of its time. Using this powerful force, the Hungarian king fought wars against the Turkish armies and stopped the Ottomans during his reign. After Matthew's death, and with the end of the Black Army, the Ottoman Empire grew stronger, and Central Europe was left defenseless. At the Battle of Mohács, the forces of the Ottoman Empire destroyed the Hungarian army, and Louis II of Hungary drowned while trying to escape. The leader of the Hungarian army, Pál Tomori, also died in the battle. This is considered one of the final battles of Medieval times.

Timeline

Dates are approximate, consult particular articles for details Middle Ages Themes Other themes

Key Events of the 14th Century

- 1305: William Wallace was executed.

- 1307: The Knights Templar were destroyed.

- 1309: The Avignon papacy began (Pope moved to Avignon).

- 1310: Dante started writing Divine Comedy.

- 1314: Battle of Bannockburn (Scotland defeated England).

- 1315–1317: Great Famine hit Europe.

- 1328: The First War of Scottish Independence ended.

- 1337: The Hundred Years' War between England and France began.

- 1346: Stephen Dušan created a short-lived Serbian Empire.

- 1347: The Black Death (a terrible plague) began.

- 1347: University of Prague was founded.

- 1376: The Avignon Papacy ended (Pope returned to Rome).

- 1380: Battle of Kulikovo (Lithuania defeated Golden Horde).

- 1380: The Canterbury Tales was written.

- 1381: Peasants' Revolt in England.

- 1381: John Wycliffe translated the Bible.

- 1385: Union of Krewo, starting the Polish–Lithuanian union.

- 1385: Battle of Aljubarrota (Portugal defeated Castile).

- 1386: University of Heidelberg was founded.

- 1389: Battle of Kosovo (Serbian and Bosnian forces defeated by Ottomans).

- 1396: Battle of Nicopolis and first Ottoman conquest in Europe.

- 1397: Kalmar Union formed in Scandinavia.

Key Events of the 15th Century

- 1402: Battle of Ankara (Ottomans defeated by Timur).

- 1410: Battle of Grunwald (Poland-Lithuania defeated Teutonic Knights).

- 1415: Conquest of Ceuta by Portugal (start of Age of Discovery).

- 1415: Battle of Agincourt (English victory in Hundred Years' War).

- 1415: Jan Hus was burned at the stake.

- 1417: The Council of Constance reunited the Papacy.

- 1419–1434: Hussite Wars in Bohemia.

- 1429: Battle of Orléans (Joan of Arc's victory).

- 1431: Joan of Arc was burned at the stake.

- 1434: The Medici family rose to power in Florence.

- 1439: Johannes Gutenberg first used movable type printing in Europe.

- 1444: Battle of Varna (Ottomans defeated Christian forces).

- 1453: Constantinople fell to Ottoman conquest.

- 1455: Gutenberg Bible printed in Mainz.

- 1456: Siege of Belgrade (Hungarian victory over Ottomans).

- 1469: Catholic Monarchs (Isabella and Ferdinand) married in Spain.

- 1474–1477: Burgundian Wars.

- 1478: Muscovy conquered Novgorod.

- 1478: The Catholic Monarchs established the Spanish Inquisition.

- 1480: Great Stand on the Ugra River (end of Mongol rule over Russia).

- 1492: Reconquista ended with the fall of Granada.

- 1492: Christopher Columbus reached the "New World".

- 1494: Treaty of Tordesillas divided new lands between Spain and Portugal.

- 1497–1498: Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama's first voyage reached India after sailing around Africa.

Images for kids

-

From the Apocalypse in a Biblia Pauperum illuminated at Erfurt around the time of the Great Famine. Death sits astride a lion whose long tail ends in a ball of flame (Hell). Famine points to her hungry mouth.

-

The Battle of Agincourt, 15th-century miniature, Enguerrand de Monstrelet

-

Silver mining and processing in Kutná Hora, Bohemia, 15th century

-

Ottoman miniature of the siege of Belgrade in 1456

-

Battle of Aljubarrota between Portugal and Castile, 1385

-

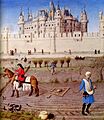

Peasants preparing the fields for the winter with a harrow and sowing for the winter grain. The background shows the Louvre castle in Paris, c. 1410; October as depicted in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

-

Miniature of the Battle of Crécy (1346)

Manuscript of Jean Froissart's Chronicles.

----

The Hundred Years' War was the scene of many military innovations. -

Dante by Domenico di Michelino, from a fresco painted in 1465

-

A musician plays the vielle in a fourteenth-century Medieval manuscript.

-

Saint John of Capistrano and the Hungarian armies fighting the Ottoman Empire at the Siege of Belgrade in 1456.

-

King Matthias Corvinus's Black Army Campaign.

Gallery

-

Peasants in fields

Très Riches Heures. -

Charles I

(Kingdom of Hungary) -

Jan Hus

(Bohemian Reformation)

See also

In Spanish: Baja Edad Media para niños

In Spanish: Baja Edad Media para niños

- List of basic medieval history topics

- Timeline of the Middle Ages

- Church and state in medieval Europe

- Jews in the Middle Ages